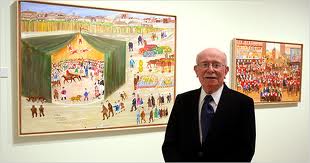

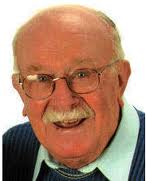

For most of his adult life North York resident Mayer Kirshenblatt’s hobby was sailing and taking camping trips into the bush. But at his family’s repeated urging, the retired paint-and-wallpaper merchant took up the painter’s easel about 1990 to record on canvas the many colorful scenes he remembered from his boyhood in Poland.

For most of his adult life North York resident Mayer Kirshenblatt’s hobby was sailing and taking camping trips into the bush. But at his family’s repeated urging, the retired paint-and-wallpaper merchant took up the painter’s easel about 1990 to record on canvas the many colorful scenes he remembered from his boyhood in Poland.

Kirshenblatt was born in 1916 in Opatow (Apt), a town he left with his mother and siblings in 1934 to join his father who was already in Toronto. Sixty-four years later, he spends much of his time creating primitivist folk paintings that recount in loving detail how life was in the world he left behind — a world that is no more.

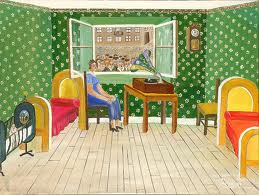

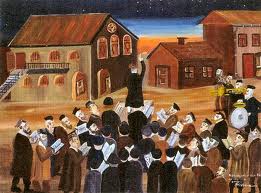

His paintings show diverse scenes of Jewish life such as the busy marketplace, the interior of the synagogue, an old-fashioned klezmer band, a funeral procession with professional mourners, and family groupings on ceremonial occasions. The paintings are vivid, colorful, richly detailed, and imbued with the sort of magical varnish that only a lifetime of memory can supply.

Some of the paintings illustrate old folk tales about Opatow. Schwartze Chassane or Black Wedding, for instance, shows a group of Jews dancing and drinking eerily in a cemetery. The story supposedly originated in the era after the War of 1812 when Opatow was struck with a devastating cholera epidemic.

Some of the paintings illustrate old folk tales about Opatow. Schwartze Chassane or Black Wedding, for instance, shows a group of Jews dancing and drinking eerily in a cemetery. The story supposedly originated in the era after the War of 1812 when Opatow was struck with a devastating cholera epidemic.

“The rabbi decided to have a wedding in the cemetery to petition the dearly departed to intervene with the Lord to help them with the epidemic,” Kirshenblatt explains. “They danced and drank amidst the graves until late at night and sure enough, two days later the epidemic subsided.”

Another painting shows another wedding, this one involving a hunchbacked bride in an advanced stage of pregnancy; Kirshenblatt claims it is based on a real episode. “The groom didn’t want to marry her but he was forced into it. Twenty minutes after the marriage she had a nice baby boy.”

When he began painting, Kirshenblatt enrolled in art lessons but quit after the first lesson. “They have nothing to teach me,” he told his wife, Dora. Then he began producing his extraordinary canvases, which seem the work of a Jewish male counterpart to Grandma Moses. The perspectives are flattened, the figures stylized, the somewhat surrealistic compositions laden with telling details. The works are narrative in the sense that each one tells a story.

“My husband, he’s the kind of person who when he looks, he sees,” says Dora Kirshenblatt. “We were after him for 10 years to get him to paint.”

“My husband, he’s the kind of person who when he looks, he sees,” says Dora Kirshenblatt. “We were after him for 10 years to get him to paint.”

Kirshenblatt is nothing if not prolific. The walls of his house are covered with his creations and dozens more are in storage. In conversation, he gives the impression that his brain is equally overflowing with artistic ideas. Yet when asked where his creativity comes from, he shrugs. “I don’t know, it’s just there.” How does he choose his subjects? “I don’t consciously decide on a subject. It just comes to my mind and I do it.”

His goal, the spry octogenarian declares, is to leave a legacy of works that reflect the richness of life in pre-war Poland. “I certainly do not wish to minimize or diminish the experience of Holocaust survivors, but they talk as though there was no life in Poland before the war. I say there was a life in Poland before the war, a very rich cultural life.”

The more he contemplates and discusses that lost world, the more he remembers of it, he says. And his art seems to spark more art. “I have a dialogue with each of my paintings,” he says, explaining that he would rather keep them than sell them. So far he has sold only a few works and has priced the others high to discourage would-be buyers who encounter them in exhibitions.

“The purpose of the paintings is to perpetuate the memory of Jewish life in the small towns of Poland. For someone to take one of them and hang it in his room, where no one else would see it, wouldn’t be fulfilling the purpose. That’s not what I want.”

“The purpose of the paintings is to perpetuate the memory of Jewish life in the small towns of Poland. For someone to take one of them and hang it in his room, where no one else would see it, wouldn’t be fulfilling the purpose. That’s not what I want.”

Kirshenblatt has had major shows at the Koffler Gallery, the Royal Ontario Museum, the YIVO Institute in New York and other important venues. Toronto-based filmmaker Jack Kuper made a short documentary, Shtetl, on Kirshenblatt several years ago, and an American publishing house is currently producing a coffee-table book about him and his art for release next year. He eventually intends to bequeath his collection of works to a major Jewish institution, perhaps the Jewish Museum in New York.

In the meantime, he seems content to continue with his art. “My wife thinks I’m an artist, my children think I’m an artist, but me, I don’t know,” he offers. “I don’t paint because of the money. I paint because I have a compulsion to paint. It beats watching TV.” ♦

© 2004

EARLY ART SHOW OF MAYER KIRSHENBLATT, TORONTO 1994

Three generations of a Jewish family squeezed around a seder table with a ghostly Elijah at the door; a youth in a school uniform on a street, clutching a store-bought herring; a group of congregants outside a synagogue on a clear night, blessing the new moon; scenes of the busy marketplace in Opatow — these and many other rich images of pre-war Polish Jewish life go on view this week in a remarkable debut exhibition of paintings by Mayer Kirshenblatt at the Koffler Gallery, 4588 Bathurst Street.

Three generations of a Jewish family squeezed around a seder table with a ghostly Elijah at the door; a youth in a school uniform on a street, clutching a store-bought herring; a group of congregants outside a synagogue on a clear night, blessing the new moon; scenes of the busy marketplace in Opatow — these and many other rich images of pre-war Polish Jewish life go on view this week in a remarkable debut exhibition of paintings by Mayer Kirshenblatt at the Koffler Gallery, 4588 Bathurst Street.

Mr. Kirshenblatt’s vivid, primitivist “memory paintings” deal with the impoverished townsfolk he knew before he left his native town of Opatow, Poland in 1934 at the age of 17, long before Germany’s “Final Solution” would eradicate most of those townsfolk and three million of their co-religionists across Poland.

Asked for an adjective to describe his own art, Mr. Kirshenblatt — a retired paint and wallpaper merchant who took up the painter’s easel only four years ago — wastes no time in offering the word “Innocent.”

At 78, he appears at least a decade younger, a spry, ruddy-cheeked, mustachioed man with flecks of paint on his fingers. (Those same hands crafted a collection of Jewish folk toys that have twice been exhibited in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.) Almost daily, he goes to the JCC Health Club, where most of his friends are concentration camp survivors.

“We sit down, we talk, and no matter what subject we start with, within five minutes we’re talking about the concentration camp.

“I certainly do not wish to minimize or diminish the experience of Holocaust survivors, but they talk as though there was no life in Poland before the war. I say there was a life in Poland before the war, a very rich cultural life.”

A group of boys in cheder; a washer-woman cleaning clothes; townsfolk gathered around a well to draw water; adults holding live chickens overhead in the pre-Yom Kippur ceremony of Capores; a funeral procession entering the Jewish cemetery, chock-a-block full of stones — canvas after canvas reflects magical, richly detailed moments, depicted boldly through the overgrown memory of childhood.

Mr. Kirshenblatt has a keen eye and the makings of a raconteur. Each one of his paintings contains a story, and he seems to relish its telling. For the benefit of those who inspect his paintings without his narration, small cards beside each painting offer explanations of relevant folklore and situational details.

For example, in one painting there appears a boy in a white shroud; since his parents had lost several sons before him, the rabbi had told them to dress the boy in a white shroud so as to confuse the angel of death into believing that he had already died. Likewise, without the cards, some innocent eyes may not immediately recognize the occupation of the woman wearing the brazen red dress in the town square.

Naive and nostalgic, Mr. Kirshenblatt’s canvases illustrate a lost world. He says he would rather keep them than sell them; one day he hopes to donate them to a major Jewish institution.

“The purpose of the paintings is to perpetuate the memory of Jewish life in the small towns of Poland,” he says. “For someone to take one of them and hang it in his room, where no one else would see it, wouldn’t be fulfilling the purpose. That’s not what I want.”

Mayer Kirshenblatt’s “Folk Paintings of Jewish Life in Poland, 1920-1934,” opens April 20 and runs to June 1 (1994). The artist gives a talk at the Koffler Gallery, Sunday May 15, 2 p.m. ♦

© 1994

************************