Toronto novelist Alison Pick, whose book Far to Go was on the list of 13 contenders for the 2011 Man Booker prize announced in July, says she has benefited from the honour even though Far to Go did not make the three-title short list that the Man Booker jury released on September 6.

Toronto novelist Alison Pick, whose book Far to Go was on the list of 13 contenders for the 2011 Man Booker prize announced in July, says she has benefited from the honour even though Far to Go did not make the three-title short list that the Man Booker jury released on September 6.

“I think at my stage I have won already, just by getting on the long list,” she told this interviewer in August. “I’ve sold the book in other countries and my agents have had lots and lots of interest. I feel the book is reaching readers it would not otherwise have reached.”

Far to Go, which is Pick’s second novel, won the 2010 Canadian Jewish Book Award for fiction. It is a Holocaust story set in the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939 around the time of the Munich Agreement and as the Nazis moved in and began to deport the Jews to concentration camps.

Far to Go focuses on the travails of one family, the Bauers, as the Nazi noose begins to tighten. Pavel Bauer is a factory owner, husband to Annaliese and father of six-year-old Pepik. The story is told largely from the point of view of the Bauers’ nanny, Marta, who is having an affair with Ernst, a trusted family friend who works in Pavel’s factory.

Marta keeps mum about Ernst’s plan to gain control of Pavel’s assets in case the latter is deported. Naïve and uncomprehending of the Nazi’s overall plan for the Jews, she seems indifferent to the fate of the Bauers except as to how it might affect herself. But her attachment to Pepik is genuine.

As secular Jews, the Bauers pay more attention to Christmas than to Jewish holidays. But Pavel still feels a strong attachment to his Jewish heritage and will not consider Annaliese’s suggestion to have their son baptised for his own protection. Nonetheless, Annaliese secretly takes the boy to a priest, who asks: “Water or papers?” In other words, should he actually perform the baptism or just provide the necessary paperwork indicating it was done? (Annaliese goes for the full deal.)

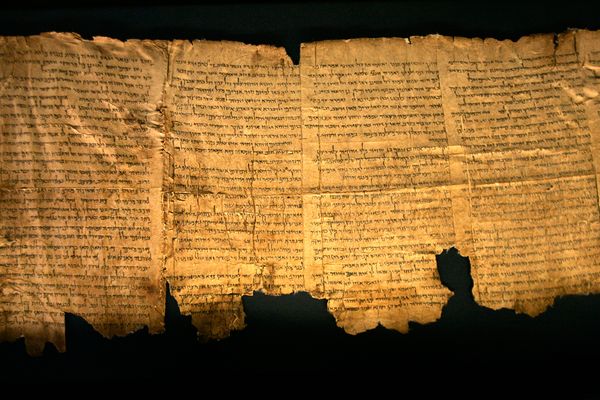

Although described on the book’s sleeve as an “epic historical novel”, Far to Go seems nothing of the sort. For me, that term evokes works such as War and Peace, Gone With the Wind, and earlier lyrical-heroic counterparts such as the Iliad and the Odyssey, not to mention the Hebrew Book of Kings.

Pick’s real achievement lies in re-creating the mundane everyday world that the Bauers inhabited as political events transform them from ordinary upper-middle-class citizens into refugees fleeing for their lives. This she does with an admirable degree of verisimilitude.

Pick’s real achievement lies in re-creating the mundane everyday world that the Bauers inhabited as political events transform them from ordinary upper-middle-class citizens into refugees fleeing for their lives. This she does with an admirable degree of verisimilitude.

There is nothing particularly heroic or noble about any of the characters in Far to Go. They are ordinary people, reduced by circumstances imposed on them into hunted creatures who must give up almost everything they possess to disappear into the night. Perhaps their most outstanding accomplishment is that, despite obstacles, they manage to place their son onto a kindertransport to England, saving his life.

Far to Go generates considerable tragic irony by framing the Holocaust-era story within a mystery tale set in recent times. In the modern story, a researcher uncovers

Holocaust documents related to the Bauers and friends that bureaucratically indicate their various fates (“died Auschwitz 1943”). The mysterious researcher, whose identity is revealed as the story unfolds, seeks out a key figure from the Holocaust tale and explains her special relationship to him.

The framing device is a common feature of Holocaust stories (think of Hannah’s Suitcase, Fugitive Pieces and Schindler’s List) but Pick lends it a post-modern flourish by allowing her two modern characters to admit that they have jointly written the novel’s central Holocaust story. It is Pick herself, of course, who has actually invented everything in the novel after careful study of many historical sources. The assertion of these two characters that they wrote much of the book seems to undermine its realism and give it some of the fuzziness of myth.

As historical fiction, Far to Go imposes tight limitations on period and character. Most of its scenes are set within the Bauer residence and we are given few glimpses of the larger society in which the characters lived. This seems a very narrow slice of life in comparison to the expansive canvases of old-fashioned three-generational sagas such as Isaac Bashevis Singer’s The Family Moskat or Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks. Far to Go is nicely streamlined in accordance with modern sensibilities.

The novel also seems to touch a chord with modern readers because it satisfies the popular Jewish quest to reach back into time and retrieve, as best we can, our ghosts from the Holocaust. Indeed, Pick says she wrote the book as part of a deep personal quest to learn about her own family’s past.

Her grandparents were Czech Jews who escaped to Canada in 1939, settling in Sherbrooke, Quebec, where her father was born in 1944. Raised in Kitchener-Waterloo, Pick grew up vaguely knowing of the well-guarded secret of her Jewish roots, but it was something no one in her family would talk about until after her grandmother’s death ten years ago.

“My Dad grew up not knowing that he was Jewish,” she said. “He was in the cemetery in Prague when he was a young man in his early 20s, and the tour guide told him that Pick is a Jewish name. He asked his parents and they did tell him they were Jewish, but there was still an atmosphere of secrecy until my grandmother died. She was really the one who didn’t want to talk about it. She lost both her parents in Auschwitz and her way of coping with that was just to deny.”

In her own life, Pick has turned her family’s journey into a circle. Several years ago the thirtyish author and her husband converted to Judaism, and are raising their young child as a Jew. ♦

© 2011