In the 19th century, as author-historian Ronald Sanders once observed, Jews in Tsarist Russia tended to perceive their cousins in Galicia as almost a breed apart, “with their strange Yiddish accent and irksome quality of seeming coarseness combined with Germanic airs of cultural superiority….”

In the 19th century, as author-historian Ronald Sanders once observed, Jews in Tsarist Russia tended to perceive their cousins in Galicia as almost a breed apart, “with their strange Yiddish accent and irksome quality of seeming coarseness combined with Germanic airs of cultural superiority….”

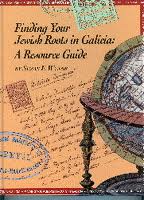

I can’t (or won’t) comment on the relative truth of this cultural stereotype, but I will say, after perusing Suzan Wynne’s impressive guidebook for exploring one’s Jewish roots in Galicia, that the very region of Galicia seems to present numerous irksome and rather coarse difficulties for modern Jewish genealogists.

Galicia today is a hybrid province with a complex shape and dozens of administrative districts bound by common history. Once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the territory straddles a geopolitical fence, its western half in Poland, its eastern half in Ukraine. If this poses certain linguistic, cartographic and other challenges for researchers, so does the fact that the Mormon LDS Family History Library, which holds an abundance of Jewish records from many other regions of Poland, possesses very few Jewish records from either Western or Eastern Galicia.

Even in Polish and Ukrainian archives, Jewish marriage records in particular are scarce due to a set of restrictive laws imposed by the Habsburg monarchs near the turn of the 19th century. Only one male from each Jewish household was legally permitted to marry, and then only by paying a burdensome marriage tax. Most Jews were married beneath the sturdy canopy of their religious tradition as always, but they did not often register their marriages with the civil authorities.

In Finding Your Jewish Roots in Galicia: A Resource Guide, Suzan Wynne expertly describes these and other research conundrums, offering plenty of solutions along the way. As Wynne demonstrates in this ripe encyclopedic compilation of resources and advice, she and other experienced genealogists have poked and probed into the vagueries of Galician archival research long enough, and evidently with such diligence and persistence, that much useful information on available resources and how to gain access to them has come to light.

A founder of the special interest group Gesher Galicia, Wynne has been absorbed with the special problems of Galician-Jewish genealogical research for the past 20 years. In Finding Your Jewish Roots in Galicia, her mature knowledge of the subject is further enhanced by contributions from numerous other experienced researchers such as Fay and Julian Bussgang, Jeffrey Cymbler, Alex Dunai, Alexander Kronick and members of Gesher Galicia.

The book opens by presenting a brief history of the “Austrian Crownland” known as Galicia, paying particular attention to the once semi-independent city-state of Krakow and the once-considerable involvement of Jews in the liquor trade. There is an interesting aside into the occupation of propinacja — “propinators,” or proprietors of Jewish taverns — along with a propinacja list from Tarnobrzeg in 1779, supplied by Michael Honey, showing that many Jews already carried patronymic-style surnames.

As the chapter on “Jewish Vital Records” details, the Austrian government established a system for the civil registration of births, marriages and deaths (B, M, D) in 1784. However, almost no Jewish records from this early era have yet surfaced. Of singular importance to researchers, this chapter contains sections on where to find vital records in both Eastern and Western Galicia. This material is made all the more valuable because (I surmise) the relevant archives do not seem to possess fully adequate and reliable finding aids.

The records shown for Eastern Galicia include many from the Zabuzanski Collection, which currently resides in two archives in Warsaw; Wynne explains that “zabuzanski means ‘other side of the River Bug,’ which separates Poland from Ukraine.” More records have surfaced in the main archive of Lviv (previously Lvov and Lemberg). Records for hundreds of towns in some 40 districts of Eastern Galicia are described in detail. Some entries contain highly personalized notes, describing items that one researcher in particular may have turned up, or useful notations such as the following, regarding birth records in Chorostkow: “The 1874-77 register is in terrible condition. It may have once been under water.”

Though less detailed, Wynne’s entries for Western Galicia usually hold their ground against the comparable listings in Miriam Weiner’s recent landmark publication, Jewish Roots in Poland: Pages from the Past and Archival Inventories (1997). In a few instances Wynne and Weiner differ on what records are available on Polish soil for a given place; for Tarnobrzeg, for instance, Wynne describes a wider array of vital records; in other instances, however, Wynne does falls short of Weiner. This observation is not made to disparage either of these outstanding publications, but rather as a comment on the mammoth difficulties inherent in gathering intelligence (especially at a distance) about resources in places behind the former Iron Curtain — localities that may still seem to repose behind a diaphanous veil through which light does not easily penetrate.

Though less detailed, Wynne’s entries for Western Galicia usually hold their ground against the comparable listings in Miriam Weiner’s recent landmark publication, Jewish Roots in Poland: Pages from the Past and Archival Inventories (1997). In a few instances Wynne and Weiner differ on what records are available on Polish soil for a given place; for Tarnobrzeg, for instance, Wynne describes a wider array of vital records; in other instances, however, Wynne does falls short of Weiner. This observation is not made to disparage either of these outstanding publications, but rather as a comment on the mammoth difficulties inherent in gathering intelligence (especially at a distance) about resources in places behind the former Iron Curtain — localities that may still seem to repose behind a diaphanous veil through which light does not easily penetrate.

Finding Your Jewish Roots in Galicia describes many other resources for Galician research, including Holocaust-related sources from yizkor books to lists of names in 1940 radiograms; sources on the world wide web; and town name indexes from important bibliographic resources such as Pinkas Hakehillot and Le Toledot ha-Kehillot be Polin.

In varying degrees of detail, the book offers lists of relevant holdings in the Ukraine Central State Historical Archives in Lviv, the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, YIVO, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Jewish Historical Institute and other institutions. The book also offers advice on travelling to Poland and Ukraine and appendixes on writing letters to Polish archives, synagogues and cemeteries in both Eastern and Western Galicia, and a summary of the comparatively vast amount of archival material available on the Jewish community of Krakow.

Besides being an indispensible work for anyone in search of their Galician ancestry, Finding Your Jewish Roots in Galicia: A Resource Guide is a handsome volume, with an attractive cover, two delightful antique maps for endpapers, and many old documents and black-and-white photographs for illustrations. All I found lacking was a good, clearly detailed map from 1918 or perhaps earlier — that, and perhaps a bit more historical insight into the inner lives, dreams and aspirations of the Galitzianer Jews whom we want so much to know. All in all, however, the publication of this book can only be taken as yet another triumphant sign of how the field of Jewish genealogy seems to be coming of age in the twilight years of this century. ♦

© 2000