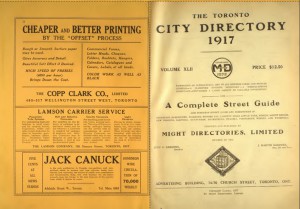

From the Toronto Star Weekly, September 1913

◊ Note: This article describes the very diligent efforts that went into producing Toronto’s city directories of a century ago. This is good news for genealogists because it assures us of the reliability of the directory information. However, individuals of Chinese, Macedonian and other “foreign” ancestry were not always listed accurately.

◊ Note: This article describes the very diligent efforts that went into producing Toronto’s city directories of a century ago. This is good news for genealogists because it assures us of the reliability of the directory information. However, individuals of Chinese, Macedonian and other “foreign” ancestry were not always listed accurately.

Toronto and Detroit are credited with having the best directories in the world for completeness and accuracy. Detroit’s is compiled by the largest directory company in existence, and the head of it lives in Detroit. Perhaps that is why.

How is Toronto’s directory made? What is done to insure the accuracy of names in a city of nearly half a million?

It is a twelve-month’s job every year. For eight months after the last directory has been issued the “in-house” staff is at work preparing for the canvassers of name-takers who do the work of revision for the next two months, and the printers spend the rest of the time.

In a few days one hundred men will start out to garner the names for the 1914 book. The city is divided into streets rather than districts, and divisions are made even of the sides of streets. Each canvasser is supplied with a sheet of paper containing the names of those who lived on the street last year, one name to each sheet. These are taken from the lists that are arranged alphabetically, and include those who are rooming as well as the tenants of the houses.

In addition there are sheets whose contents will make up the first part of the directory, in which the numbers on the street appear consecutively with the name of the occupant attached. Corrections are made in the street lists; the individual names are checked off if correct, or struck out if they no longer live on the street, and the names of newcomers are added. These separate names are collected, and later classified in an alphabetical manner, and contain the house address and the occupation as well.

Basis for New Directory

The sheets carried by each canvasser are printed by a special machine, from type that was set up nearly one year before from the previous year’s directory, and kept standing in vaults, over 1,200 pages of it, 173,000 names, tons in weight. These names are the basis for the new directory, just as the old edition of a dictionary is the foundation of the new.

The task of the name-takers for 1914 is to make corrections and additions to the records that were correct for 1913.

A page of the directory of 1914 will not look much this year’s. Any more than 1912 and 1913 bore anything more than a distant cousinly resemblance. Taking the city as a whole, less than 36 [?] per cent. of the names will be repeated from the old book, unchanged. This may be illustrated as follows:

These changes, incredibly large, are not confined to the outlying districts.

Many Changes on Streets

In a single year, from No. 310 to No. 313 Yonge Street, there were 14 changes out of 17 names.

On Bay street, 20 in 25 names.

On Adelaide street, 21 in 28 names.

On King street west, 22 in 24 names.

On the east side of Emmerson avenue, a residential district, there were 34 changes in 31 names, over 100 per cent. In other residential streets the changes are shown as the following:

Spadina road, 19 changes in 26 names.

Armstrong avenue, 19 changes in 34 names.

(etc – hard to decipher)

Dead Men as Detectives

Are any of the name-takers guilty of napping on their work; of deferring to the names as they have them on last year’s lists without bothering to make the corrections?

That is what the manager wants to know, and he uses dead men as his detective agency.

A number of “Catch” slips are prepared containing the names of men who lived at certain addresses last year, but since have died or moved elsewhere, usually the former. Each name-taker has one or more of these mixed up with his street lists. If he returns any of these as being all correct without change, he is dismissed without compunction, or the chance of an appeal. It is thus made risky to “ditto” a single name without investigation. A considerable number of name-takers fall by the wayside by this simple test each year, and the weeding out ensures an honest record.

The house-to-house process is only a part of directory building. There are many supplementary processes. It may be that a boarding house-keeper forgets a name in giving a record of her lodgers. If the lodger is employed in even a medium-sized concern his name will be secured, for the directory sends out blank forms to employers for filling in with the names and addresses of employees. In one case 15,400 are forwarded to one firm. All the replies are tabulated in alphabetical order and the names that have been already received from the regular name-takers are struck out. Repeated efforts are made to trace persons whose names have appeared in the last directory, and have not been returned from the corresponding firms or any other source, and special trips are made to the places where they were credited with living in the old book.

Calls are Repeated

If no one is in a house when a call is made, the canvasser is instructed to make two other calls and finally to get the information next door if he cannot get it directly. In the case of vacant houses calls are made repeatedly to within a short time of going to press.

The supreme faith of many wives in the importance of their husbands leads to some troublesome — rather than numerous — discrepancies. It is guarded against, however, by previous experience of this feminine trait.

“He’s General Manager of the firm. Oh yes, I’m certain he is.”

And “general manager,” without capitals, is set down in the canvasser’s book and the name is sent on to be allocated in the general alphabetical list. But the newly acquired honour may be in jeopardy. Probably the same name occurs in the list of employees sent in by the firm, but now he is only assistant to so-and-so. There is a discrepancy and the firm — not the wife — is called up to straighten it out. The firm’s reply comes by phone, and what it says naturally goes. If the wife sees the directory later she feels annoyed at the “mistake,” or learns something she did not know before.

This work of phoning for special information is done by two girls who spend their whole time searching for a clue to names that are not duplicated from the previous year, or verifying doubtful information, or checking up contradictions.

Others of the inside staff complete that useful addition at the back of the book, names of societies, clubs, lists of judges, city officials, provincial officers, etc. These entail weeks of enquiry and clerical work.

Omitted Deliberately

When such diligence is used to follow up single names, are there any that are omitted deliberately? A few, chiefly foreigners. The temporary inmates of a Macedonian lodging-house on Eastern avenue could never see their names in the directory. They have no commercial value, the names of such birds of passage. Nor is every Chinaman honored. “Jim Lee” of Spadina avenue and “Jim Lee” of Queen street may happen to choose the identical nomenclature. In the absence of middle names, of which they seem shorn, and with no one able to distinguish features except two or three police court defense lawyers or chief inspector Archibald, and with their faculty for shuffling off such earmarks even as these English nicknames, what matters it what they are called? Being worthless as information, the names are not allowed to encumber the directory, and the place of abode is marked “Chinese laundry” — for by any other name than Jim Lee’s it “would smell as sweet.”

The diligence in compilation, applied with constantly improving methods, has produced each year a book that is more nearly complete and so the percentage of the number of names to the total population has gone up steadily. With the size increasing the price has followed. For instance, 1905 — number of names, 21,915, price $3. 1906 — number of names, 37,823, price $6. 1913 — number of names 131,000, price $10.

For twenty years the directory of Toronto cost $1, then $6, from then up to 1913 it was $7.60; now it is $14; and when Toronto has 200,000 people the price with jump to $15. The selling price just pays for the actual cost, the “ads” do the rest.

Preparing Trade Lists

A new phase of the works that seems to be a natural off-shoot of the business of collecting names is the preparation of trade lists for mailing purposes. 1,000,000 names all over Canada are on them. Every death or change of address is noted.

The most interesting department to the outsider is the babies. Practically all the births appearing in any paper in Canada are recorded, and the lists sent out daily to many firms. If the children die, the names are struck off and the notifications sent to these firms. Then there are lists of six months’ old children, audited for certain kinds of goods kept in stock by various firms; other lists of one-year-olds are kept track of from the original birth notices.

Hence, when Mrs. Henry Johnson, in her far-off home in Johnson’s Corners on the edge of the prairies, receives samples of baby’s foods, ads of garments, or youthful bicycles, or guns or swords, she wonders why. All can be traced back to this original three-line item in Johnson’s Corner’s correspondence of the Calgary Eye Opener. “Our esteemed Overseer, Hal Johnson, wears a smile these days; it is a boy.” ♦