◊ After the departure of Rabbi Benjamin Friedberg from Toronto’s Beth Tzedec Synagogue in the early 1990s, the congregation turned to Rabbi Baruch Frydman-Kohl to lead it into the future. The following is an excerpt from The History of Beth Tzedec Congregation Toronto Canada (2016). It is being published as Rabbi Frydman-Kohl departs from Beth Tzedec after more than a quarter-century of devoted service.

RABBI FRYDMAN-KOHL AND THE FUTURE

The search was on for a new senior rabbi, and the issue of women’s inclusion in synagogue rituals was a divisive factor. In the 1930s and 1940s, the advocates for change had fought for mixed seating; in the 1970s, they had fought for the right of women to vote in synagogue elections. Now, in the 1990s, they were lobbying for women to receive aliyot, an honour up till now selectively granted on special occasions.

The search was on for a new senior rabbi, and the issue of women’s inclusion in synagogue rituals was a divisive factor. In the 1930s and 1940s, the advocates for change had fought for mixed seating; in the 1970s, they had fought for the right of women to vote in synagogue elections. Now, in the 1990s, they were lobbying for women to receive aliyot, an honour up till now selectively granted on special occasions.

The issue had simmered through the last years of the Friedberg era, and the congregation, like many in the Conservative fold, was divided. Political campaigns had been waged and board elections had been fought over it. Just as Goel Tzedec had been torn apart eight decades earlier over whether to hire an English-speaking rabbi, the congregation was now polarized over the selection of a rabbi who would decide the question of women’s involvement in religious rituals. As board chairman Bill Cass wrote, he and the other board members wanted above all to reconcile the diametrically opposed factions within the shul.

How do you bring them together? It’s one thing to be logical and legalistic; it’s another thing to continue to live together in peace. How can this be done? . . . . There will be no changes in ritual practice without a period of study and dialogue so that everyone can understand why a particular change is allowed and why others are not. Any change will be introduced on a gradual basis . . . It is my fervent prayer that as our new rabbi becomes integrated into our community, he will establish his credentials here and build strong bonds of trust so that he can truly be a spiritual leader and guide who will ease the transition into any changes that are made.

During the selection process (throughout which Irvin Beigel, who had been Benjamin Friedberg’s assistant, served as acting rabbi), the Men’s Club conducted a membership survey that showed that nearly two-thirds of respondents wanted more involvement of women in synagogue rituals. Apart from that, a majority felt that the new rabbi should be between 40 and 55 years old, and that he should focus more on pastoral duties and education as opposed to community leadership.

During the selection process (throughout which Irvin Beigel, who had been Benjamin Friedberg’s assistant, served as acting rabbi), the Men’s Club conducted a membership survey that showed that nearly two-thirds of respondents wanted more involvement of women in synagogue rituals. Apart from that, a majority felt that the new rabbi should be between 40 and 55 years old, and that he should focus more on pastoral duties and education as opposed to community leadership.

With respect to observance, while the Rabbinical Assembly committee of Jewish law and standards permitted driving to the nearest shul on Shabbat, no Conservative rabbi in Toronto would do so, and only those candidates willing to conform to traditional standards were being considered. As various candidates visited the shul, a rumour started circulating that the committee was prepared to accept someone who was not shomer shabbos. Bill Cass felt obliged to dispel this in the bulletin with the following statement: “There is no question that any rabbi whom we hire will be observant of the Sabbath as practiced according to ‘Minhag Toronto’ (Toronto custom).”

The candidate who was ultimately hired, Baruch Frydman-Kohl, was interviewed by two successive boards, each with different politics, and yet a third board was in place to welcome him by the time he arrived in September 1993. Coming from a smaller and more casual Conservative synagogue in Albany, New York, he found the adjustment challenging, perceiving a “rigid formalism” at Beth Tzedec under which nothing in the service, no matter how small or seemingly innocuous, could be altered. For example, once at the end of a Shabbat service he invited some children up to the bimafor some grape juice, and was later advised by a senior congregant that such a thing was “not done”. That incident seemed telling.

On the matter of women and Torah reading, Rabbi Frydman-Kohl said that he viewed the issue of one of “rites” rather than “rights”, since Judaism is a religion that puts responsibilities above privileges. He set about educating himself and the congregation on this topic through courses and a series of guest lectures, and after a year presented a “responsum” (a written scholarly decision) that women could indeed receive Torah honours. This resulted in some members accusing him of attempting to transform Beth Tzedec into a Reform congregation!

On the other hand, another action he took regarding Torah reading was an alteration in the shul’s longstanding approach to the weekly parsha. Upon his arrival, he had been surprised to discover an unusual system which had likely originated at the old McCaul Street Synagogue under Rabbi Reuben Slonim and had prevailed throughout the entire Rosenberg and Friedberg years: instead of a full reading of the parsha each Shabbat, the pattern was to read the first aliyah of the week on Saturday afternoon, the second on Monday morning, the third on Thursday morning, and aliyot four through seven on the following Sabbath morning. He restored the full reading of the parsha on Shabbat, thereby projecting an image of traditionalism alongside his openness to change regarding women.

As part of his vision of pastoral healing, Rabbi Frydman-Kohl wanted to resolve some of the historic ill feelings from the Rosenberg era. In November 1995, a series of annual public lectures in memory of Rabbi Stuart and Hadassah Rosenberg was inaugurated through the generosity of David and Karla Goldberg and family. (Karla, an artist, was the creator of the parochet [ark curtain] in the main sanctuary.) At the first lecture, which featured the esteemed Israeli novelist Amos Oz, executive director Jack Orenstein opened the evening with some warm and touching reminiscences, recalling Rabbi Rosenberg’s inspirational sermons, his prolific writings, the Great Weekends and Institutes he had initiated, the art, the museum, the adult education program, the school, the camp, the campaign for Soviet Jewry and, above all, his oratory. The Rosenberg memorial lectures continued for five years.

Another move to heal the past was made in 1996 when Rabbi Frydman-Kohl invited Rabbi Benjamin Hollander to return to Beth Tzedec to lead the alternative High Holiday services. Rabbi Hollander became part of the High Holiday “line-up” for over a decade, until his death in 2008.

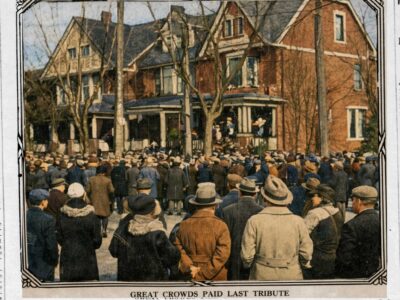

A second significant reconciliation took place in December 1998, when Rabbi Reuben Slonim was invited to deliver what would be his last sermon at Beth Tzedec, and was presented by Rabbi Frydman-Kohl with a citation from the Jewish Theological Seminary for his years of service. Rabbi Frydman-Kohl would later recall Rabbi Slonim’s reaction to this honour: “As I read the words, he wept and in a whisper said that he was glad to finally come home.” Rabbi Slonim was stricken with illness soon afterwards, and died in January 2000.

Rabbi Frydman-Kohl’s skills on the pastoral front have proven legendary, as anyone will attest who has watched him make his rounds, day after day, week after week, in response to the never-ending procession of life-cycle events—births, marriages, deaths—within his flock. The pastoral demands of a congregation as big as Beth Tzedec’s cannot be underestimated, and require constant attention. “He’s a very strong ‘people person’,” said former congregational president Bob Cohen. “His associations with people are, in my estimation, one of his strengths.”

In 2006, all members of the congregation were invited to fulfil the mitzvah of helping to inscribe a new Torah scroll in honour of Rabbi Baruch Frydman-Kohl to mark his thirteenth year at Beth Tzedec. Organized by members Patti Rotman, Ilene Flatt, Bernie Shiner, Elaine Steiner, and Cheryl Cappe, the event was launched in November with a “BARuch Mitzvah” kiddush luncheon and an evening of dinner and dancing; and throughout the winter and spring, donors and friends had the opportunity to participate in “Mitzvah 613” and try their hand at the scribal arts.

The event culminated at Shavuot the following May, when a procession of members carried the newly completed scroll into the sanctuary. It resides in one of the arks to this day, a tribute to the respect and affection in which Rabbi Frydman-Kohl is held by the congregation he has served for so long. ♦