Funded solely by Germany and managed by the Red Cross, the International Tracing Service (ITS) of Bad Arolsen, Germany, has built up a vast Central Names Index of more than 50 million reference cards pertaining to some 17.5 million people, mostly victims of the Holocaust and family members who made inquiries about missing relatives after the war.

Funded solely by Germany and managed by the Red Cross, the International Tracing Service (ITS) of Bad Arolsen, Germany, has built up a vast Central Names Index of more than 50 million reference cards pertaining to some 17.5 million people, mostly victims of the Holocaust and family members who made inquiries about missing relatives after the war.

The word “victim” does not refer just to the people who perished in the Holocaust, explained Israeli genealogist Michael Goldstein during his well-attended talk about the ITS documents at Shaarei Shomayim Synagogue on November 4th 2009 as part of Holocaust Education Week. “People who were displaced and did survive — they too were the victims,” he said.

Opened to researchers since 2006, the vast repository of Holocaust-related records that the ITS has accumulated and generated since 1955 is contained in five office buildings, some of which are crammed wall to wall with filing cabinets. The ITS has about 400 employees and is governed by an international committee of 11 countries, Goldstein said.

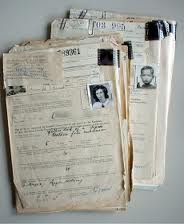

The ITS documents have been scanned and may also be searched at both the Yad Vashem Museum in Jerusalem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, Goldstein said, adding, however, that by agreement they will never be posted on the internet. The documents include incarceration lists, transport lists, medical assessments and hospital records, prisoner of war and displaced person records, birth, marriage and death records, ship manifests and much more.

Some people have found handwritten letters their parents had written, describing their experiences in the war. One researcher found “a postcard written from a sister to a brother from one displaced person camp to another,” he said. “That’s a letter that the family would never have seen. Now it’s available.”

When Goldstein visited Bad Arolsen a couple of years ago as part of a group of 40 researchers, the ITS assigned a team of 20 staff members, including translators, to assist them. “They tried to be as helpful as possible. Some of them had been working there for 20 or 30 years and had never had [face to face] contact with researchers before.”

Two hours north of Frankfurt by train, the town was at the juncture of the American, Russian, French and British zones at the end of the Second World War. The former home of an SS training school, it became the headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces near the end of the war. The ITS was established there with records assembled by the American, British and French forces. The Russians, however, took their war-related documents back to Russia.

The original mandate of the ITS was to register Holocaust victims but it later began helping to reunite families. Whereas once it typically took two or three years to reply to a letter of inquiry, today its usual response time is six to 12 weeks and it has cleared up a backlog of more than 200,000 inquiries. Goldstein advised researchers to write the ITS as an efficient means of retrieving information about the fate and whereabouts of family members during and after the war.

The original mandate of the ITS was to register Holocaust victims but it later began helping to reunite families. Whereas once it typically took two or three years to reply to a letter of inquiry, today its usual response time is six to 12 weeks and it has cleared up a backlog of more than 200,000 inquiries. Goldstein advised researchers to write the ITS as an efficient means of retrieving information about the fate and whereabouts of family members during and after the war.

The ITS hosts monthly guided tours for visitors and all research is done by appointment only, Goldstein said. Recalling his own warm reception there, he cautioned that the ITS may be becoming less open and friendly than when it opened its doors to researchers in 2006.

Born in Toronto and raised in Montreal, Goldstein is a Jerusalem-based genealogist who is president of both the Israel Genealogical Society and the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies. His talk — Documenting the Fate of the Victims: Researching the Records of the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany — was hosted by the Jewish Genealogical Society of Toronto. ♦

© 2009