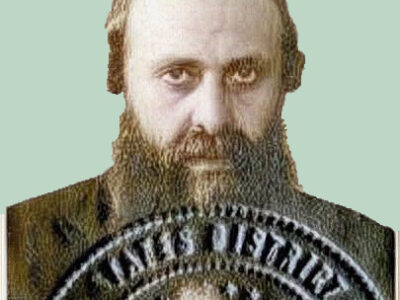

Sitting in his elegant apartment in midtown Toronto, novelist-lawyer Morley Torgov explains why his latest novel, The War To End All Wars (Malcolm Lester Books) took him 17 years to write.

Sitting in his elegant apartment in midtown Toronto, novelist-lawyer Morley Torgov explains why his latest novel, The War To End All Wars (Malcolm Lester Books) took him 17 years to write.

Whenever he felt challenged about the direction of the story, he’d put the manuscript into a drawer, sometimes for a year or more at a time. The book was also delayed, he says, by his vigorous professional routine as a lawyer.

At 72, he still works a full five-day week at the Richmond Street law firm of which he is a partner. Only after hours — on evenings, weekends and during holidays at the cottage — does he find time to moonlight as a novelist.

“Frankly, I prefer it like this,” he says. “I like it when my phone rings all the time. I like to keep busy. You know what trouble is? Trouble is when you don’t have any trouble any more.”

That may be true for Torgov, but Eliezer Pinsky, aka Elliott Pines, the protaganist in The War To End All Wars, holds an entirely different concept of trouble.

As a Russian soldier during WWI, Pinsky has a memorable battlefield encounter with a German soldier. Later, he becomes a clothing merchant in a Michigan town in which the German is his commercial rival. The two wage a fierce mercantile battle.

Both these central characters are Jewish. Torgov says he began the novel after realizing that Jews fought on opposite sides in WWI; he drew upon the experiences of his father, a Ukrainian-born Jew who had served in the Russian army.

A two-time Leacock Medal winner, Torgov=s fifth and latest novel reflects the same subtle humor and stylistic lightness that characterizes his earlier works. Although dark things happen in the book, and despite the Tolstoyan weight of the subject, the prose is never heavy or overburdened.

“I have difficulty looking at any subject with what Woody Allen used to call ‘total heavy-osity,'” he says. “I can’t stand prose that is dense and steeped in that ‘total heavy-osity.’ One of my literary idols is Elmore Leonard, who said one of the most clever things I’ve ever heard a writer say. In an interview he was asked ‘To what do you attribute the success of your prose?’ He replied, ‘I leave out the parts people don’t read.'”

That recipe may have contributed to the success of Torgov’s two most popular novels, A Good Place to Come From and The Outside Chance of Maximilian Glick, which date from the 1970s and 1980s, respectively. Both were Leacock award winners and both were made into television series by the CBC.

A Good Place To Come From, which happens to reflects Torgov’s small-town background in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., became a play that ran off-Broadway, while The Outside Chance of Maximilian Glick became a feature film starring Saul Rubinek.

Although now a big-city dweller, Torgov writes often about small-town milieus not unlike the one in which he grew up. “I don’t look on small-town life with a romantic eye,” he says. “Small-town people have a way of nosing into each other=s lives, and even lacerating each other, that is anything but folksy.”

While each of his novels center principally around Jewish characters, their appeal is universal, and many non-Jewish readers have told him that they identify with his characters and their problems with identity and assimilation.

“I was flabbergasted after my first book came out — A Good Place to Come From — and I got cards and letters from many people saying that my experience had been just like theirs as a Catholic or a Ukrainian in a small town,” he says.

Even as he prepares two more manuscripts for publication, Torgov says he has no plans to curtail his lawyerly activities, including the almost-daily lunches with his cronies that he relishes. “We’re always kidding each other, especially about our declining sexual functions,” he jokes.

“I could never sit at home all day, or go to the golf course, or park my behind on a beach chair by a pool in Florida,” he says. “I honestly believe that the more you use your brain, the younger you stay.

“I find that the daily challenge of coming to work and dealing with problems in the real world is very stimulating. It’s always very aggravating at times. It may not keep me forever young, but it certainly keeps me younger than I actually am.” ♦

* * *

Profile: Morley Torgov

In Morley Torgov’s new novel, The War to End All Wars (2002), two Jews who had faced each other as soldiers in the opposing Russian and German armies of WWI, confront each other again as clothing merchants in a no-holds-barred commercial battle in Oreville, Michigan, in the 1920s.

Torgov says he began writing the novel immediately after seeing a documentary about Jewish life in prewar Europe and realizing that Jews had fought on opposite sides in WWI.

His father, born in the Kamenets-Podolsk region of Ukraine, had served in the Russian army for 2-1/2 years before defecting — which is precisely the course of action of the novel’s protagonist, Eliezer Pinsky, who becomes Elliot Pines in America.

A two-time Leacock Medal winner, Torgov’s latest novel reflects a subtle humor and lightness of style, qualities that also mark its predecessors. Although dark things happen in the book, the prose is never heavy or overburdened. Torgov agrees with this reader’s assessment that his writing style is ‘accessible,’ and cites Isaac Bashevis Singer, Joseph Heller and Philip Roth as major influences.

“I have difficulty looking at any subject with what Woody Allen used to call ‘total heavy-osity,’” he says. “I can’t stand prose that is dense and steeped in that ‘total heavy-osity.’ One of my literary idols is Elmore Leonard, who said one of the most clever things I’ve ever heard a writer say. In an interview he was asked ‘To what do you attribute the success of your prose?’ He replied, ‘I leave out the parts people don’t read.’”

Even though Torgov’s latest story unfolds in the small town that is also characteristic of his other novels such as A Good Place to Come From and The Outside Chance of Maximilian Glick, he argues convincingly that the adjective “folksy” does not apply to either the writing or the characters.

“Writing about small-town people doesn’t necessarily entail folksy writing,” he says. “Small-town people have a way of nosing into each other’s lives, and even lacerating each other, that is anything but folksy. I don’t look on small-town life with a romantic eye.”

Born 71 years ago into the small Jewish community of Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., Torgov is a partner in a Richmond St. law office, where he still maintains a full working schedule. Each workday except Friday, he normally takes a brief nap after work, then puts in another two or three hours on his writing.

“On holidays I’ll write longer at the cottage,” he says. “But at my age, I don’t have the energy to do an all-night writing session like I used to.”

While each of his five novels center principally around Jewish characters, their appeal is universal, and many non-Jewish readers have told him that they identify with his characters and their problems with identity and assimilation.

“I was flabbergasted after my first book came out — A Good Place to Come From — and I got cards and letters from many people saying that my experience had been just like theirs as a Catholic or a Ukrainian in a small town,” he says.

While Torgov is “always conscious” of his Jewish identity, “I wouldn’t want to waste time on trying to determine whether I’m a Jewish-Canadian writer or a Canadian-Jewish writer. . . . I’m very comfortable being Jewish. I wouldn’t want to be anything else — except maybe Italian. I love the language and the food.”

The War To End All Wars was a challenge to write, he says. He began it in 1981 and worked on it intermittently for the next 17 years, consigning it to a drawer for years at a time while he finished other books. He honed out its chapters in chronological order and rewrote each paragraph more than a dozen times before handing over the final manuscript to his literary agent Beverly Slopen and Toronto publisher Malcolm Lester in 1997.

“The reason this was the most difficult book for me to write is that it is a plot-driven book — all my other books were more character-driven,” he says. “I don’t know where I’m going when I start a book. But if you really know your characters and there’s enough conflict between them, they’ll carry the story forward. That’s how it worked for me.” ♦

© 2002