Sonny Lapinsky, the memorable hero of Karen X. Tulchinsky’s engaging novel The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky (2003) is a Toronto boxer who wins the world middleweight crown at Madison Square Gardens in 1948 and again in 1954.

Sonny Lapinsky, the memorable hero of Karen X. Tulchinsky’s engaging novel The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky (2003) is a Toronto boxer who wins the world middleweight crown at Madison Square Gardens in 1948 and again in 1954.

Like a champion boxer, the novel itself has impressive staying power and seems nowhere near ready to leave the ring. If the literary sphere were anything like boxing, the book would have reached the intermediate rounds by now.

Raincoast Books of Vancouver, which published it in 2003, produced a Canadian trade paperback version in 2004 and plans to release a first edition this month in the United States. As well, movie rights have been sold to Ocular Productions, a Winnipeg film company that has hired Tulchinsky — a former Torontonian who teaches screenwriting at the University of British Columbia — as principal scriptwriter.

Because it draws so fully upon the characters, settings and myths of Toronto’s Jewish community from the ‘20s through the ‘50s, The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky may be likened to Mordecai Richler’s celebrated novel The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, which was painted against the backdrop of Jewish Montreal.

The fact that Moses Lapinsky may soon reach the big screen, as Duddy Kravitz did three decades ago, is just one of several notable points of comparison between the two novels.

Both present lovable but emotionally crippled protagonists against a realistic social background that dips into the criminal underworld. Also, both are graced with colourful gangster kingpins: Tulchinsky’s larger-than-life Checkie Siegelman with his fancy cars and fat cigars, and Richler’s immortal Jerry Dingleman, feared and loved as the immortal Boy Wonder.

As another of comparison, both novels are relatively rare examples of Jewish tales set partially in the Holocaust era that do not deal centrally with the Holocaust. Whether Moses Lapinsky packs the long-term clout of Duddy Kravitz remains to be seen, but it’s certainly a worthy contender.

Presented as a fictitious academic biography, The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky traces the history of Yacov and Sophie Lapinsky and their sons Sid, Lenny, Sonny and Izzy throughout the Depression, WWII and postwar eras. The story focuses on a genuine historical event, the Christie Pits riot of August 1933, as a pivotal occurrence that deeply affects the family’s fortunes in the chosen homeland of Canada.

The narrator is Moses Nino Lapinsky, Sonny’s middle child, a professional historian who probes into and embellishes his family’s history and the city’s Jewish past from the retrospective distance of half a century. “My father was a poor Jewish kid from an immigrant family, from the ghetto at College and Spadina, a neighbourhood in which you were more likely to grow up and become a thief, a bookie, a gambler or dead, than a world renowned boxing champion,” he tells us as he begins his colour commentary on the family saga.

Although he purports to be delivering an objective biography, he shows little concern for sports-related stories. Instead, his concern is the family’s deeply personal interior life and emotional background. Thus, while some scenes are set in the gym and boxing ring, many more take place around the Lapinsky dinner table. Others take place in bowling alleys, newspaper offices, department and grocery stores, delicatessens, restaurants and the sidewalks and back alleys of downtown streets like Manning, Palmerston, Harbord, College and Spadina.

Although he purports to be delivering an objective biography, he shows little concern for sports-related stories. Instead, his concern is the family’s deeply personal interior life and emotional background. Thus, while some scenes are set in the gym and boxing ring, many more take place around the Lapinsky dinner table. Others take place in bowling alleys, newspaper offices, department and grocery stores, delicatessens, restaurants and the sidewalks and back alleys of downtown streets like Manning, Palmerston, Harbord, College and Spadina.

The book follows two Lapinsky sons overseas during WWII and provides impressively realistic descriptions of Dieppe and other battles. Several scenes of pogrom violence in 1913 Romania are depicted through flashbacks. However, the story’s main battle occurs locally, right here in Toronto.

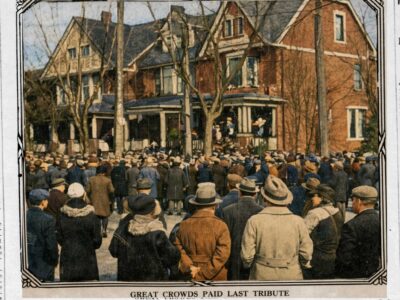

It’s the summer of 1933. In east-end Toronto, a gang of toughs form an organization, the Swastika Club, to keep Jews off their beach. Taking their animosity into a Jewish neighbourhood, the so-called Swazis unfurl a large swastika flag at a baseball game in Christie Pits park. The action provokes a riot that draws in thousands of people and goes on for days. Five-year-old Izzy is injured in the Christie Pits riot and left permanently brain-damaged. The event becomes a central traumatic episode in the family saga. Eventually, through retelling, it is transfigured into myth, and permanently floats above the family’s mental horizons, like the Romanian pogrom that devastated Yacov’s family two decades earlier.

Sonny, who was babysitting Izzy when the accident occurred, is consumed with guilt, rage and sorrow. “All the feelings under the sun, every emotion known to humans and God ricochet relentlessly through Sonny’s battered nine-year-old body.” Normally a charmer with a sweet crooked smile, he finds emotional release only through punching and hitting. Finding a natural outlet in the boxing ring, he puts himself into training. Soon Checkie Siegelman spots him, recognizes his potential, and becomes his manager.

Tulchinsky provides highly realistic depictions of all aspects of boxing, a subject she admits she knew little about at the outset. It was Sonny’s choice — not hers — that he become a boxer, she explained in an interview.

“I knew nothing about boxing,” she said, “but no matter how hard I tried to convince the character to do something else with his life, he was determined to be a boxer. So I had to educate myself on the sport. I wouldn’t exactly say I am now an expert, but I do know a right uppercut from a left hook.”

With his highly passionate nature, Sonny is also a great lover. When he meets Loretta Mangiomi, the sister of his sparring partner, she only has to look at him for that magical chemistry to take hold. “A force stronger than Johnny’s hardest, meanest right uppercut swings from Loretta’s eyes and pummels Sonny right where it hurts, in his heart, and somewhere deep in his lower belly.” Because she is an Italian Catholic, Loretta and Sonny are star-crossed lovers, faced with an instant impediment. But their attraction is too strong. Loretta becomes pregnant and Sonny marries her at City Hall, then brings her home to meet the folks. Yacov, however, will not accept his son’s marriage to a shiksa.

Years go by; Sonny and Loretta have one child and then another, but Yacov doesn’t relent. His attitude tears Sophie apart. His anger and inflexible attachment to tradition give rise to the novel’s central themes involving acceptance, compassion and forgiveness.

One of the novel’s key subplots revolves around Lenny, the second son. Lenny is not athletic like Sonny; instead, he’s the bookish and sensitive type. As a child, he’s victimized by street bullies; as a teenager, he befriends older male librarians and turns them into role models. The author uses this character to introduce themes and issues related to gender politics, but wisely does not allow any anachronistic whiff of post-modern ideology to intrude onto the page.

Keen on becoming a writer, Lenny initially works for the Yiddisher Zhurnal; fired for vague reasons, he joins the army. Ironically, his best army buddy is Charlie Bain, a former Swazi who, much to his subsequent shame, had participated in the Christie Pits riot. A far more tolerant and humane figure in his maturity, he deeply regrets his youthful acts of ignorance and malfeasance.

The book’s central motif of social violence is echoed in the pogroms, the back-alley bullying, the Christie Pits riot, the blood-sport of boxing and the rising antisemitic cruelty in Germany. Unfortunately, the theme is also carried into the Lapinsky household as domestic violence.

For Yacov, the Christie Pits calamity is a cruel echo of the Tiraspol pogrom, when marauding Cossacks killed his five-year-old brother. Days after the riot, something inside him snaps and he attempts to regain his emotional equilibrium by whipping his children.

For Yacov, the Christie Pits calamity is a cruel echo of the Tiraspol pogrom, when marauding Cossacks killed his five-year-old brother. Days after the riot, something inside him snaps and he attempts to regain his emotional equilibrium by whipping his children.

Sophie rises nobly in defense of her loved ones. At a time when men traditionally retained the upper hand at home, she orders Yacov out of the house. This key scene reveals Yacov at his worst and Sophie at her best; it highlights the male-dominated sexual ethos of the times and foreshadows the sea-change that is soon to occur.

A remarkable woman, Sophie seems a bit reminiscent of Ma Joad in The Grapes of Wrath; a tough Depression-era mother, she’s much stronger than she knows and the glue that keeps the family together. A tireless scrubber of floors and peeler of potatoes, her natural domain is the kitchen and the home; she is the heart, soul, healer and caregiver of her clan.

Sophie eventually forgives Sonny for marrying Loretta and longs to see her grandchildren. But when she raises the subject with Yacov, he is inflexible: he recites the mourner’s kaddish and “rocks back and forth at the table, like a rabbi on the Day of Atonement.”

A key conversation with her best friend, Tessie, again demonstrates how fully the story is steeped in sexual politics. An independent-minded woman, Tess tells Sophie that if she really wants to see Sonny and his family, all she has to do is go see him.

“The trick,” she explains, “is to do what needs to be done, and let him [Yacov] think it was his idea . . . . You don’t need his permission to meet your granddaughter. Believe me. A stubborn man is just waiting for his wife to make the move. Then he can blame you for it. So? What do you care about that? Pride shmide. Only men worry about silly things like pride.”

This is a moment of empowerment for Sophie. She begins to see Sonny’s family on the sly, cautiously taking the first steps that ultimately make all the difference in reuniting the family.

Although he plays no part in the central action of the novel, Moses Lapinsky, the narrator, is so important to it that his name is included in the title. A generation or two removed from the story, he is a University of British Columbia historian who explains he says he was galvanized into writing a biography of Sonny after a shoddy bio painted him as “a womanizing wife beater who neglected his children.”

To the author’s great credit, all of the main characters contain contradictions that make them more human. Sophie has moments of rage, but keeps it under control. Sonny, who typically transmutes his inner rage into violence, also has a “deep inner knowing” about spiritual matters. There’s a very satisfying unification of opposites here, as if each central character must unite with a shadow self that has always been suppressed.

What is the author’s attitude towards the violence that’s so pervasive in the novel? Clearly, she’s not a pacifist. She strongly disapproves of Cossacks and Swazis, and seems to have not the slightest admiration for boxing. However, she invites us to cheer when Sonny saves Izzy or Lenny from a bully, and she honours the brave regiments that fought the Nazis. In short, she’s a strong proponent of social justice.

The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky depicts a society rife with division and social prejudices. Many of its settings depict the dark underside of society — a shadowy realm of pool halls, racetracks, bowling alleys, bootleg joints and betting parlours. The illustrious king of this underworld realm, at least locally, is Checkie Siegelman. He’s a marvelous creation: partial to fancy suits, sparkling tiepins and spats, he smokes expensive cigars, drives expensive cars and carries a huge roll of money. He discovers Sonny in a bowling alley, where the nine-year-old was working as a monkey boy, setting up bowling pins in the very bowels of the building ; then supervises his boxing career, sporting him all the way to the “holy shrine” of Madison Square Gardens.

Because it peers into the lower depths, Moses Lapinsky is a work of low realism, composed of tragic and comic elements in almost equal proportion. As I see it, the story resolves as a comedy.

Two bookend scenes open and close the novel. In the first, Sonny is about to face his opponent in a championship match at Madison Square Gardens. It’s the bout of his life — and he spots Yacov and Sid in the audience. He’s been estranged from his father for 14 years and he turns his anger at Yacov into fighting energy. He wins the crown.

The scene that closes the story occurs two weeks later in Toronto, when the conquering hero steps into Manny’s Delicatessen, where he knows Yacov and Sid are sitting with the guys. Tulchinsky achieves more than a technical knock out with this triumphant and understated closing scene. Despite their painful separation, Sonny and Yacov wordlessly reconnect. This is the essential action of the novel — a coming together of parts, the reunion of father and son. ♦

© 2005