Miriam Weiner’s Jewish Roots in Poland: Pages from the Past andArchival Inventories is a pioneering work that presents a concise, authoritative inventory of extant Jewish records in the Polish State Archives and its regional (oddzial) branches, and in more than 2,500 Urzad Stanu Cywilnego (USC) or local town hall record offices throughout Poland.

It also provides listings of genealogically-relevant holdings in Warsaw’s famed Jewish Historical Institute and the state-run archives of two former Nazi death camps, Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Whoever said, “Knowledge is power,” knew whereof they spoke. This astonishing compilation of data offers the promise of fresh and extraordinary discoveries, and a boost – perhaps even a quantum leap – to researchers who, like myself, have long been sifting through the ashes and documentary remains of the Jewish experience in Poland.

Jewish Roots in Poland: Pages From the Past and Archival Inventories, by Miriam Weiner and various others. In Cooperation with The Polish State Archives. Large hardcover publication, 446 pages. Lavishly illustrated with hundreds of photographs, maps, and reproductions of antique postcards and documents; designed by Dorcas Gelabert. Published jointly by The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the Miriam Weiner Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc., 1997. www.rtrfoundation.org

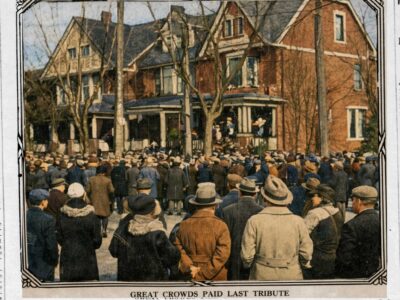

To Miriam Weiner’s immense credit, however, Jewish Roots in Poland: Pages From the Past and Archival Inventories is much more than a plain and colorless archival catalog. Its 446 pages contain hundreds of photographs of town squares, synagogues, cemeteries and other Jewish sites that poignantly evoke the memory of a vanished world. Weiner has given us a visually stunning memorial book that pays full homage to the fact that the Jewish civilization of Poland—rich, vital and thriving—was the center of the Jewish world for several centuries before 1939. As such, its appeal is bound to extend far beyond genealogists, historians and other scholars, to the Jewish mainstream.

Part archival finding aid and part memorial book, Jewish Roots in Poland is also part travel guide. It should prove immensely useful to anyone planning a heritage trip to Poland, since it provides good encyclopedic descriptions, enhanced by maps and photographs and thorough bibliographies, of 28 Polish cities that had pre-Holocaust Jewish populations of 10,000 or more.

Unlike most memorial books or travel guides, however, Jewish Roots in Poland offers a methodology to help us re-establish our familial connection to the dead. It starts (Chapter 1) by providing a detailed background in the rudiments of Polish-Jewish genealogy, with advice on yizkor books, synagogue records, old telephone directories, locating an ancestral shtetl, internet genealogy and much more. This chapter reflects the formidable expertise of its author, Jeffrey Cymbler, whose succinct articles have also appeared in this journal.

Chapter 2 contains the so-called “Pages From the Past and Present” – the above-mentioned capsule descriptions of 28 cities. The cities are: Bedzin, Bialystok, Chelm, Czestochowa, Gdansk, Kalisz, Kielce, Krakow, Lodz, Lomza, Lublin, Miedzyrzec Podlaski, Nowy Sacz, Otwock, Piotrkow Trybunalski, Plock, Przemysl, Radom, Radomsko, Rzeszow, Siedlce, Sosnowiec, Tarnow, Tomaszow Mazawiecki, Warszawa, Wloclawek, Wroclaw and Zamosc.

Chapter 3, written by the late Professor Jerzy Skowronek, former director of the Polish State Archives, provides information on the Polish State Archives, its acquisition policies, procedures, regulations and fees. (No definitive fee structure is set out in the book. Rather, an address is given where genealogists may write to attain the latest fees — which shall probably continue to rise in tandem with interest in Polish-Jewish genealogy throughout the Jewish world.) The documents that illustrate this chapter give us a glimpse of some of the treasures preserved within the Polish archives: for instance, a list of purchasers of seats and tax list for a synagogue in Siedlce, 1906; pages from the 1902 and 1931 books of residents for Nowy Korczyn; an 1806 birth record and an 1870 census record from Krakow; a Kromolow tax list, 1864; and a list of prisoners in the Lublin ghetto, 1941. More documents illustrate Chapter 4, which outlines the responsibilities of the USC offices, where local metrical records are usually retained for a period of 100 years before being transferred to the Polish State Archives.

Chapter 5 focuses on the holdings and policies of the Jewish Historical Institute (JHI) and the adjoining Ronald S. Lauder Foundation Genealogy Project. Most of the documents that illustrate this chapter are from the Holocaust era, which is a particular strength of the JHI; the Institute also holds numerous older collections, such as records from Wroclaw from the end of the 18th century to 1938; records from the province of Silesia (Slask) from 1742 to 1942; and records from Krakow from 1701 to 1939. The book offers a six-page inventory of genealogically-relevant materials from the JHI, which are listed according to the alphabetically-coded legend below. It is unclear what proportion of the JHI’s total holdings this represents, but it is presumably only a small part. Chapter 6 details the holdings of the Majdanek Museum Archives and the State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The heart and soul of the book is Chapter 7, which contain the archival inventories; they run to nearly 200 pages. The inventories are indexed by town and again by repository; there are also separate inventories for the JHI and the local USC office in Warsaw (the USC Warszawa Srodmiescie, which has extensive holdings for the former Polish provinces of Stanislawow, Lwow and Tarnopol, now in Ukraine). Twenty-two different types of documents are catalogued, and coded alphabetically as follows:

- A = army/recruit lists

- B = birth

- C = census

- D = death

- E = voter lists

- G = immigration

- H = Holocaust

- J = Judaica

- K = kahal

- L = land

- M = marriage

- N = name changes

- O = police files

- P = pogroms

- R = reference

- S = school records

- T = tax lists

- V = divorce

- W = occupation lists

- X = Jewish hospital

- Y = notary records

- Z = local government records.

To a genealogist, this is an awesome, spine-tingling list, especially when one realizes the significant number of records that reach back into the 19th century; some even predate 1808, the year that Jewish communities throughout the Polish territories were required to register their births, marriages and deaths with the civil authorities. (Jewish records were often included among Roman Catholic vital records from 1808 to 1825, but the book makes the only error I happened to catch in citing these years as 1810 to 1825.)

Like many genealogists with ancestry in the Polish territories, my own research has significantly depended until now on the Mormon LDS Family History Library, which has afforded me access to microfilmed B, M & D records from my ancestral town of Konin from 1808 to 1874. Looking up Konin in Jewish Roots in Poland, I found the original BMD records that the LDS had microfilmed. I also found more recent metrical records (1875 to 1895) housed in the Konin branch of the state archives; and, as expected, later metrical records (1895 to 1937) housed in the Konin USC office. Several isolated years are missing from the LDS microfilms for Konin, and I noted with disappointment the corresponding gaps in the original materials as well.

Jewish Roots in Poland offers a few exciting surprises regarding Konin – namely, the existence of C documents from 1807/1914 and various dates to 1940; K documents from 1893-1913; S documents from 1936-1939; and Z documents from 1895-1914. The C documents refer to the lists of inhabitants (sometimes called “spisy mieszkancow” or “skorowidz do rejestro mieszkancow”), and I would prize such a list for Konin from 1807 for its potential to corroborate ambiguous details of the early metrical records. The kahal, school and government records are also highly desirable. I quickly penned the necessary letters of inquiry regarding these documents, using the archival addresses found in one of the six appendices. I expect that Jewish Roots in Poland will similarly inspire many researchers to write to Polish repositories; and that, consequently, the center of gravity for the practice of Polish-Jewish genealogy will shift considerably from the LDS Library towards Poland. To aid researchers, Jewish Roots in Poland lists fond numbers as well as locations for almost all items.

Thanks largely to the LDS Library, researchers until now have had fairly easy access to B, M and D records, and in rarer instances to a few other categories of documents. Infrequently, as with the town of Blaszki, LDS lists “Fam” (family) records; Jewish Roots in Poland apparently categorizes these more precisely as N (name changes). For a few towns, LDS has “Cem” (cemetery) records; it does so for the town of Zmigrod, for example, but without indicating a range of years. Jewish Roots in Poland apparently refers to these with much greater precision; it shows K, Y and Z type documents for Zmigrod for 1860/1935 (the slash indicates that the material spans these years, but with gaps). In most other instances in which Jewish Roots in Poland and LDS listings are compared, Jewish Roots in Poland seems to come out ahead with more precise listings that sometimes show a slightly greater range of years, even with metrical records.

For the town of Szprotawa, for example, the LDS catalog lists BMD records, Cem records, and I/O records for 1813-1845; I/O is a rare category defined as “incoming and outgoing Jews.” I looked up the town in Jewish Roots in Poland’s list of archival holdings by town and found the corresponding BMD and Cem records, as well as G (immigration) records for 1813-1845. In addition, Jewish Roots in Poland showed Z (local government) records for 1812-1861.

The range and variety of pre-1808 documents shown in Jewish Roots in Poland is astonishing. Listings for Krakow, for instance, enumerate Jewish army recruit and tax records from the 1790s, school, hospital, voting and government records from 1701 onwards, and – peculiar as it sounds – a list of Jewish doorkeepers ca 1550. Jewish metrical records were kept for Opole from 1756 to 1781 and for Wroclaw from 1760 onwards; both towns were previously under Prussian rule, which explains why such records exist in the first place. For Tarnobrzeg, where there was an infamous blood libel case in 1757, Z type records are evidently available from 1695 and L type records from 1785; such sources may name relatives of the unfortunate Jews who were wrongly charged, convicted, tortured and killed. Other examples of early records include:

- Opole Lubelskie Z 1510/1811

- Pleszew S 1785/

- Putawy L 1785-1788

- Opatow W 1720-1729

- Stargard Szczecinski C 1742/1936

- Torun K 1725-1859

- Wielowies N 1762-1820

- Wodzislaw A 1742-1752

- Wolsztyn K 1698-1865

- Wroclaw K 1604

As Weiner points out in the Introduction, the focus of the book was initially limited to the state archives and its branches, and later expanded to include the USC offices, the JHI and the concentration camp archives. Thus, the archival inventories are not comprehensive, since they omit material held in local museums and some smaller repositories. Most of the institutions that participated usually checked and updated the information as necessary before publication. In some instances, archivists declined this task, owing to the sheer bulk of materials listed (especially from the C category, the lists of residents). Disturbingly, some Jewish metrical books that the LDS Library microfilmed in the 1960s and 1970s could not be found; Weiner reports that “in a significant number of cases, the individual archive directors simply crossed out the entry on the verification inventory list and were unable to state where the material might be.” This raises a worrisome question: How many metrical books that were never microfilmed have also disappeared?

Striving to make the book as user-friendly as possible, Weiner provides a list of the relatively few archives that excluded themselves from this massive inventory project, so that it is clear that a particular omission was due to organizational problems (for example) rather than to insignificant holdings. The book is filled with useful addresses, helpful hints, colorful maps, guides to Polish and Russian handwriting, and many other extras: the select bibliography runs to 30 pages. Numerous photos of archives buildings will give researchers a better sense of what to expect on a visit to Poland.

Beyond question, Jewish Roots in Poland is the finest primary source ever published for anyone involved in Polish-Jewish genealogical research. Compiled with the cooperation and blessing of the Polish State Archives, Miriam Weiner’s extraordinary magnum opus is a product of its times: it simply could not have been attempted before the collapse of communism. It is as much a reflection of our day and age as the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the cinematic masterpiece Schindler’s List, and the internet phenomenon known as JewishGen. Just as awareness of the Holocaust has been filtering down to the masses, so too has awareness of the possibilities of Jewish genealogy. Given that 75 per cent of all American Jews have at least one ancestor from Poland, this book will likely make the general Jewish population more aware of those possibilities than ever before.

What will Miriam Weiner do for an encore? Not to worry. Jewish Roots in Poland is the first of three proposed volumes. A book on Ukraine and Moldova, and another on Belarus and Lithuania, are in the planning stages. ♦

© 1998