Three years after her controversial book The Traitor and the Jew exposed anti-semitic and Nazi-sympathizing sentiments in Depression-era Quebec, Esther Delisle is working on a second book, this one about an underground “pipeline” that enabled French Nazi collaborators and war criminals to escape to French Canada after World War II.

Three years after her controversial book The Traitor and the Jew exposed anti-semitic and Nazi-sympathizing sentiments in Depression-era Quebec, Esther Delisle is working on a second book, this one about an underground “pipeline” that enabled French Nazi collaborators and war criminals to escape to French Canada after World War II.

“I’m looking at the Canadian connections that helped such people come here,” said Delisle, who has been dubbed Quebec’s Nasty Girl. “I can prove that certain people were part of the connection, but there are still pieces of the puzzle that are missing.”

So far, Delisle’s research has turned up more ex-Nazi collaborators from France than she initially suspected. The most infamous of them, Count Jacques Dugé de Bernonville, was “a higher-ranking official than Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyons — he was really a very major killer.” She has uncovered evidence that former provincial premier Maurice Duplessis hired one collaborator “to pull some dirty tricks in the Vatican.” Among many other strands, she is also investigating Georges Simenon, the detective novelist, who lived in Quebec briefly after the war.

A postdoctural fellow in the history department of Montreal’s McGill University, Delisle, a French-Canadian Catholic, wrote The Traitor and the Jew (Robert Davies Publishing, Montreal) originally as a PhD thesis while attending Laval University. Associates told her that she was committing academic suicide; it took two years instead of the usual period of three to six months for an academic committee to approve the work.

Available in both of Canada’s official languages, the book became a Canadian bestseller, and has fueled the bitter resentment of many separatists in Delisle’s native province. Critics often mention Delisle in the same breath with Montreal author Mordecai Richler, who quoted her extensively in his lengthy critiques of Quebec anti-Semitism and nationalism that appeared several years ago in the New Yorker magazine and were republished in the book “O Canada, O Quebec.”

Quebec premier Jacques Parizeau and other prominent separatists have disparaged Delisle for painting a negative image of the province. Ordinary citizens, too, have found unique means of expressing their displeasure: a shopping mall manager was so disgruntled by her presence at a book store that he disconnected the electricity. “I’ve been pushed and kicked around so much that now, if you really want to hurt me, you have to push me very hard,” Delisle said. “Otherwise, I just burst out laughing.”

Still, she expresses satisfaction that her work is having an effect, and that student audiences have welcomed her warmly. “I’m doing my own research and I enjoy it. I’m getting some recognition in France. So what if the kings of the tribe here don’t like me? I don’t need their recognition. I want to be an outstanding historian.”

The Traitor and the Jew is a stunning expose of the nationalistic ideology of the province’s revered right-wing historian-cleric-novelist, Abbé Lionel-Adolphe Groulx (1878-1967), whose supporters have long dismissed as marginal his anti-semitic, anti-liberal diatribes, which were often written under pseudonyms. Delisle showed that they were as prolific as they were shocking.

The Traitor and the Jew is a stunning expose of the nationalistic ideology of the province’s revered right-wing historian-cleric-novelist, Abbé Lionel-Adolphe Groulx (1878-1967), whose supporters have long dismissed as marginal his anti-semitic, anti-liberal diatribes, which were often written under pseudonyms. Delisle showed that they were as prolific as they were shocking.

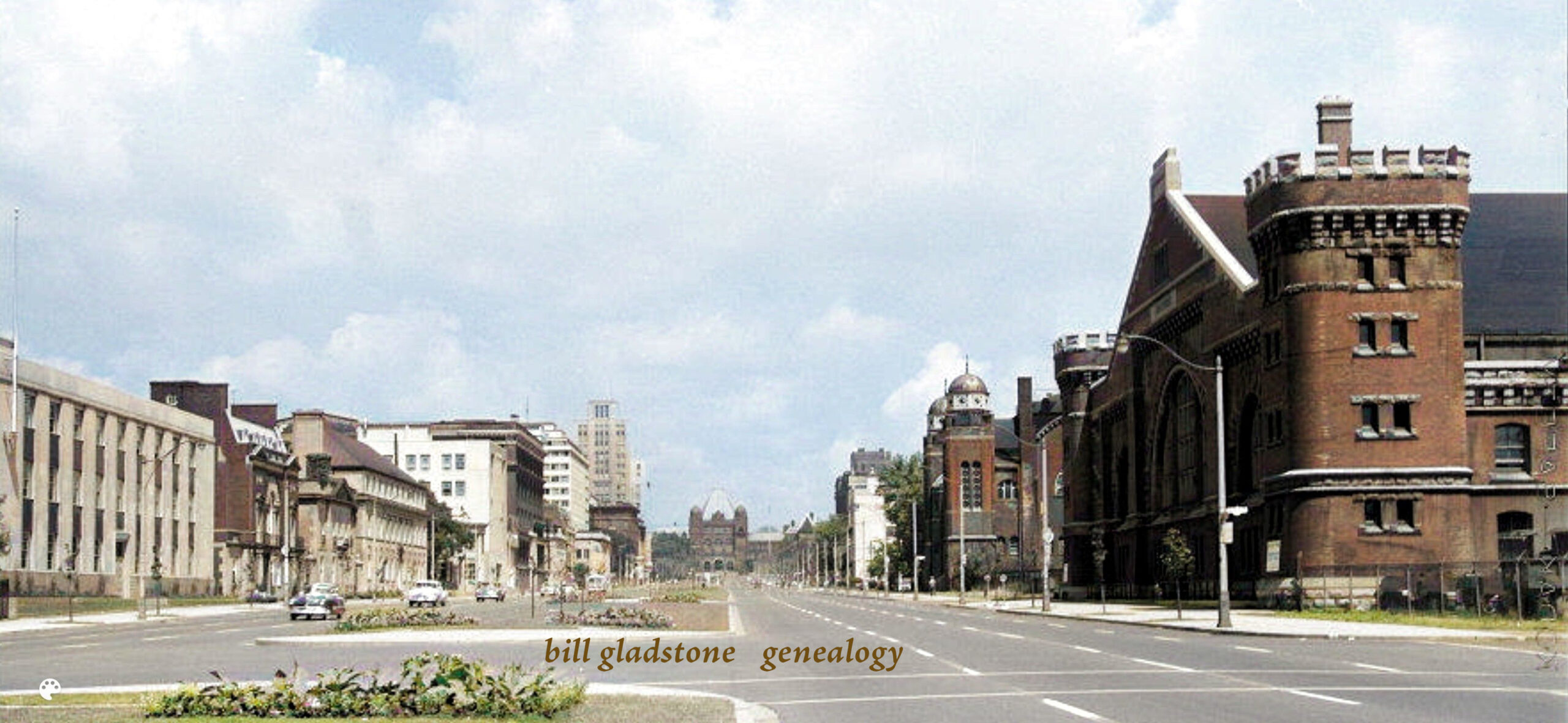

Like the Nazis, with whom he was in profound sympathy, Groulx built up a racial ideology based on blood purity, tribal warfare and the concept of a superior race. He yearned for a fascist leader to arise in Quebec to help lead the French Canadians back to what he imagined were their homogenous and unadulterated Roman Catholic roots. He proposed an “Achat Chez Nous” (“Buy-At-Home”) program as a means of boycotting Jewish shops, and may have distributed a version of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion under a pseudonym. Still, he is regarded as a hero within Quebec, and many streets, buildings, and even a Montreal metro station have been named after him.

The Traitor and the Jew also exposes the racist ideology of three other Quebec institutions of the 1930s: Le Devoir, the leading nationalist daily newspaper; l’Action nationale, the leading nationalist monthy journal; and Jeune-Canada, the leading nationalist youth organization. The book quotes a former and somewhat repentent member of Jeune-Canada, Andrè Laurendeau: “At the same time as Hitler was preparing to kill six million Jews, the Jeune-Canada movement spoke very sincerely of a ‘supposed mistreatment,’ an ‘imaginary persecution’ that they contrasted with the oppression — ‘quite real in this case’ — that the French Canadians suffered here. I can still see myself, hear myself bitching as loudly as I could during the meeting, while that same night, some poor German Jew must have been trying to save his family from death by leaving Germany. …”

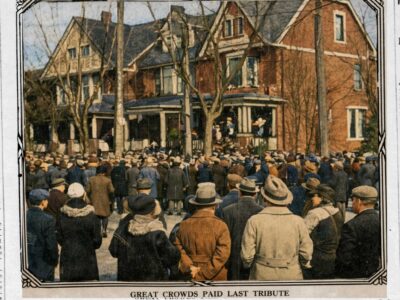

Working with historian John Hellman, a specialist in French history, Delisle is attempting to shed light on the five years that Count Dugé de Bernonville, the high-ranking French Nazi collaborator, spent in Canada after his arrival in 1946. Evidently, church officials, the mayor of Montreal, the St. Jean Baptiste Society and various federal and provincial politicians exerted much pressure to keep him in Quebec even as the federal government was trying to deport him. “Ninety-nine point nine per cent of Quebec’s intelligentsia at that time rallied around him,” said Delisle. Expelled from Canada in 1951, de Bernonville went to Brazil, where he was murdered in 1971.

And what was Simenon doing in Quebec? Evidently, he left France after the war and lived briefly in St.-Marguerite-du-Lac-Maisson, a town north of Montreal that, perhaps only coincidentally, was the place of residence of Baron Louis-Philippe Emprain, a wealthy Belgian with strong alleged fascist ties. Dotted with the summer homes of wealthy Montrealers, the region saw large pro-Nazi rallies in the 1930s and even attracted Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign policy advisor and later foreign minister, as a summer visitor.

“The FBI has a big file on Simenon,” said Delisle. “But they make so many demands on you before letting you see anything. I’m still waiting.”

Delisle is convinced that a Nazi underground operated in Quebec as late as 1972, when an escape route to Quebec was apparently prepared for Paul Touvier. The infamous French Nazi collaborator and war criminal chose instead to stay in France, however, insisting he had done nothing wrong. His recent war-crimes trial proved otherwise, shaking France and resulting in conviction.

Discussing Quebec’s recent fever-pitch referendum on sovereignty, which the federalists won by a whisker, Delisle insists it was no accident that so many sovereigntist leaders distinguished between “ethnic” voters and “pur laine” or old-stock Quebeckers. She and many Canadians have recognized that a determined ethnic nationalism underlies Quebec’s separatist movement, despite the whitewashed, inclusive “territorial” nationalism that the Parti Quebecois officially espouses.

When federal separatist leader Lucien Bouchard refers to Quebeckers as a “white race” in need of a higher birth rate, as he did recently; when deputy premier Bernard Landry, a former minister of immigration, publicly berates a hotel employee because “you immigrants” prevented the Quebecois from realizing their nationalist dream; when “Le Quebec aux Quebecois!” becomes the haunting, exclusionary chant at separatist rallies — these are disturbing signs, according to Delisle and many others, of a deeper, darker reality.

Like many Canadians both inside and outside Quebec, Delisle was shocked when Premier Parizeau blamed money and the ethnic vote for the separatist defeat, and swore a revenge that he himself will likely never deliver, since he resigned in a storm of controversy the next day. “I was speechless for a moment, which is no small achievement,” she said. “No kidding, it really shut me up for a while. Then I realized: he’s not the first one to say it, many others have said such things.

“So what was his big mistake? It was that he said it in front of foreign journalists. That’s the mistake! That’s the mistake that Mordecai Richler and I made, too. Richler published an article in the New Yorker. You don’t say those things outside the tribe — and Parizeau said it for the whole world to see.” ♦

© 1995