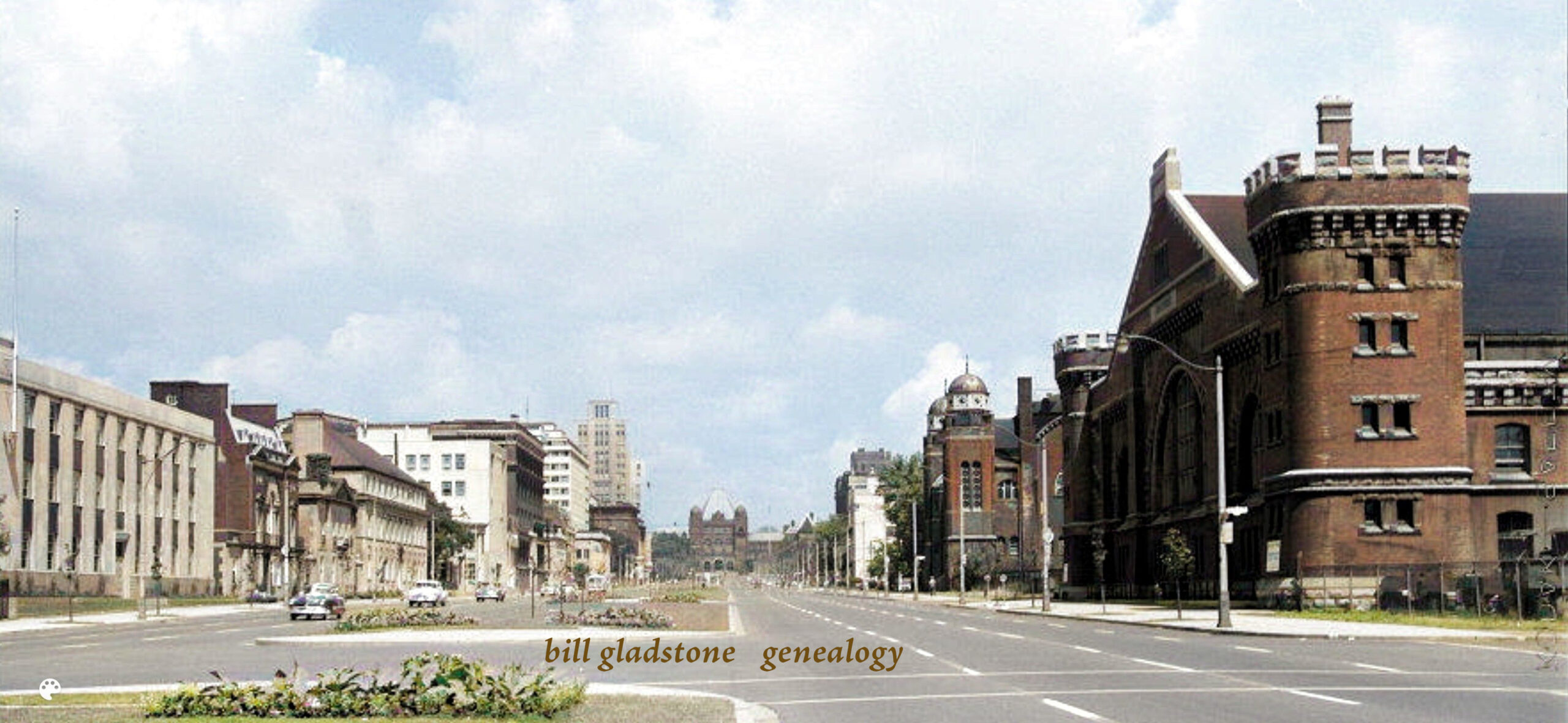

Numerous writers of special interest to the Jewish community appeared recently at the Harbourfront International Festival of Authors, Toronto’s pre-eminent literary event. Their presence insured that Jewish themes were well represented.

Numerous writers of special interest to the Jewish community appeared recently at the Harbourfront International Festival of Authors, Toronto’s pre-eminent literary event. Their presence insured that Jewish themes were well represented.

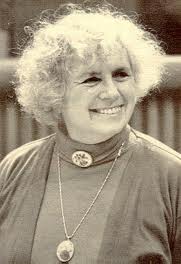

American Jewish writer Grace Paley, interviewed publicly by Toronto newspaper columnist David Lewis Stein, spoke engagingly about art and politics, the two activities to which she has devoted most of her 73 years. She is known equally as an ardent antiwar campaigner, feminist and writer of exquisite short stories (anthologized by Farrar Straus Giroux as The Collected Stories).

The recent Million Man March in Washington D.C. “may worry our Jewish hearts and hurt our feelings,” she said, “but it has the Republicans and Democrats really worried — and whatever worries them must be a good thing.”

Did she regret spending so much time on politics, so little on art? “For me, politics has been a great interest all my life, and I’m only sorry I did too little,” she said. “I’m not sorry I didn’t work more, I’m sorry I didn’t write more politically.”

Among writers who influenced her, she credited James Joyce, Gertrude Stein and especially W.H. Auden for having the greatest effect. From Joyce she learned “a lot about spareness, about not throwing in a lot of extra stuff,” and from Auden she learned “how to write British,” which she did for more than a year. To develop their talent, young writers need to pay a lot of attention to “the sounds of home,” said the Bronx native. “I would never have written if I didn’t live a house where English, Yiddish and Russian were spoken.”

* * *

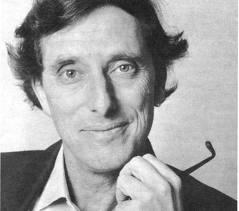

Hailed as one of the most important literary voices to come out of Latin America, Ariel Dorfman, born in Argentina in 1942, is a Chilean citizen who was forced into exile after the 1973 coup that overthrew Salvador Allende.

Hailed as one of the most important literary voices to come out of Latin America, Ariel Dorfman, born in Argentina in 1942, is a Chilean citizen who was forced into exile after the 1973 coup that overthrew Salvador Allende.

“When Allende became president of the country, something very special happened in our lives,” Dorfman recalled. “It was that everyday people found they were able to change the world. It’s such an extraordinary concept … very few people can feel they can change the world.”

“The world does not have to be the way it is,” he said. “People don’t have to live in fear: we can change the world. That experience was absolutely fundamental to me.”

After the coup ended Allende’s democratic revolution, “I couldn’t write for two and a half years, I was so filled with remorse and sorrow,” he said.

The author of many titles such as Death and the Maiden and the recent Konfidenz, Dorfman said that he sees the world “as a struggle between stories,” many of which are suppressed by dictators who impose their own realities upon the masses.

“If I’m proud, it’s because I’ve provided some spaces for these stories to tell themselves,” he said. “After 20 to 30 years of writing, I’ve found I can be as complex as I am, yet as clear and simple as a story requires.”

* * *

Fifty-year-old Australian novelist Thomas Keneally, who is not Jewish, has increased public awareness of the Holocaust through his 1982 Schindler’s Ark, which won the Booker Prize and which Steven Spielberg translated to the screen as Schindler’s List. To date, the book has sold more than two million copies, making it by far the most popular of Keneally’s roughly 20 novels.

Fifty-year-old Australian novelist Thomas Keneally, who is not Jewish, has increased public awareness of the Holocaust through his 1982 Schindler’s Ark, which won the Booker Prize and which Steven Spielberg translated to the screen as Schindler’s List. To date, the book has sold more than two million copies, making it by far the most popular of Keneally’s roughly 20 novels.

“Coming from Australia, I never understood the power of anti-semitism,” he said, calling it an “illusory passion” that requires neither a rational reason nor the presence of Jews in a nation to exist. “Some of the strongest haters of Jews are in areas like Montana, Idaho and Washington, where there are no Jews. These people may have never met a Jew, yet they hate them.”

Anti-semitism is “a moveable feast,” he said. “People claim the Jews are behind both the Bolshevik and the capitalistic conspiracies. Luther blamed them for carrying the bubonic plague. … When it was shown that bubonic plague is caused by bacteria, people made up another reason to hate.”

For Keneally and his readers, Oskar Schindler has been “the lens through which we can look at the Holocaust.” Researching the book “was appalling,” he said, “because I never knew that people could perform such horrors on each other.” ♦

© 1995