“I’m working on a book of family history,” Sara Edell Kelman declares, as she shows me her massive collection of archival documents, ketubot, photographs, Yiddish letters and other family memorabilia, spilling out of diverse albums, binders and boxes. “No, it’s more than one book — it’s a series of books. There’s a lot of stuff here, and it’s sprouting wings and branches on all sides.”

“I’m working on a book of family history,” Sara Edell Kelman declares, as she shows me her massive collection of archival documents, ketubot, photographs, Yiddish letters and other family memorabilia, spilling out of diverse albums, binders and boxes. “No, it’s more than one book — it’s a series of books. There’s a lot of stuff here, and it’s sprouting wings and branches on all sides.”

A noted genealogist who lived in Chicago and Boston for years, the former Sara Edell Schafler returned to the city of her birth four years ago to become the wife of Rabbi Joseph Kelman of Toronto’s Beth Emeth Bais Yehuda congregation. A former president of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Boston, she has numerous research projects on the go, all involving aspects of Toronto’s Jewish community.

Born in Toronto in 1928, she attended the Brunswick Talmud Torah, Harbord Collegiate and the University of Toronto before leaving for New York in 1949 to study at the Jewish Theological Seminary. Then she and her former husband, the late Rabbi Sam Schafler, raised a brood of kids. Only in retrospect did she realize that her children would know practically nothing of her family’s long association with Toronto.

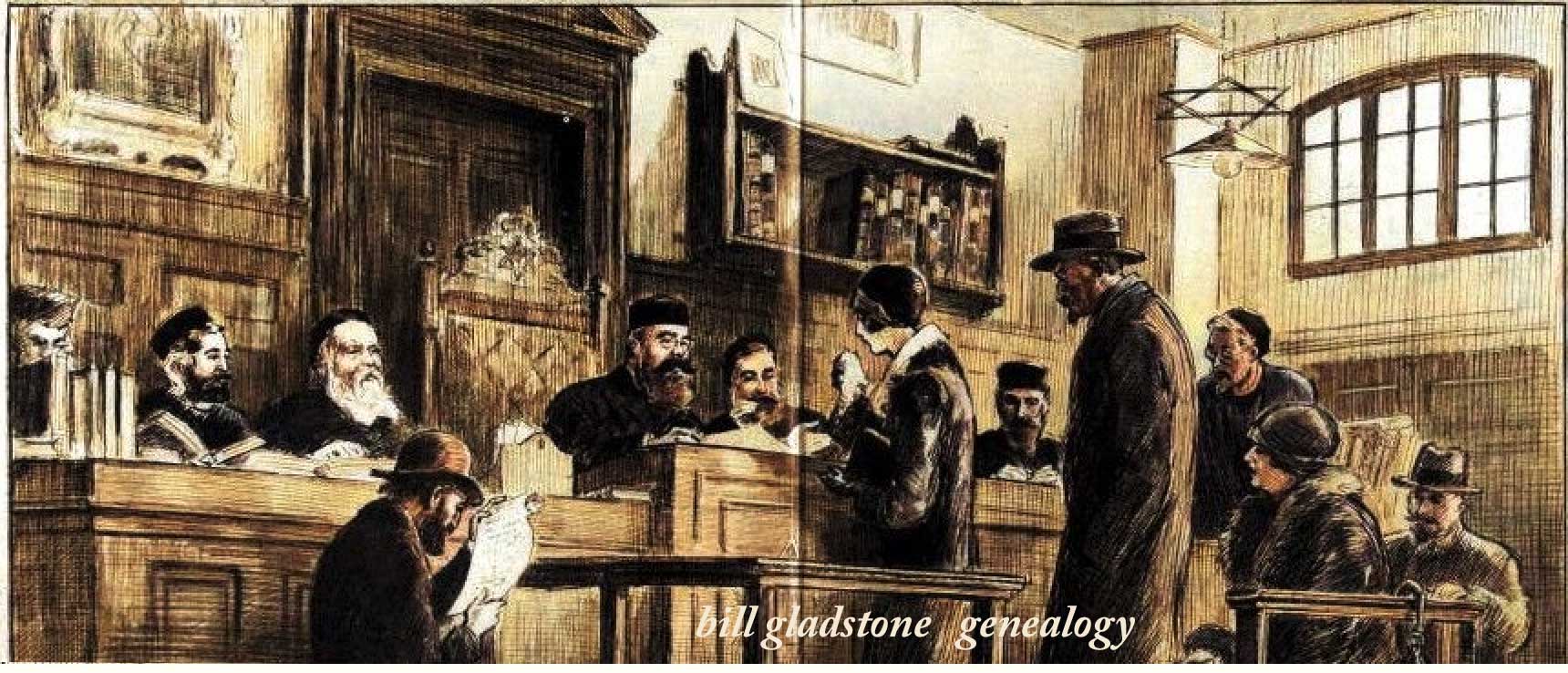

Kelman’s grandfather, Rabbi Joseph Weinreb, was an impressive figure in the community’s early days. Before the turn of the century, when he was still in Europe, the Shomrai Shabbos congregation wrote to him, offering a pulpit. He arrived in Toronto in 1900, became known as the Galitzianer Rav, and served as a rabbi here for more than 40 years.

In 1980, during one of her frequent visits to the city, Kelman took a highly nostalgic walking tour led by archivist-historian Stephen Speisman. Afterwards, she read Speisman’s book, The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937, and discovered details about her grandfather she hadn’t known before. While she had always believed he had come from Pamorin (Pamoryzany), according to Speisman the illustrious rav was working in Jasi, Roumania when he received the Toronto invitation.

Questions began to gnaw away at her. How long had he been in Jasi? Where did the family come from before that? Who was her great-grandmother, after whom she’d been named? “I felt guilty that I never asked my mother or grandfather about her. What did she look like, what was she like? I began to think about those things, the things I didn’t record. These people have a right to be remembered.”

Smitten with the genealogical bug, she interviewed elderly relatives, traipsed through cemeteries and visited libraries and archives from Salt Lake City to Poland, Jasi to Jerusalem. And by a fluke, she found a relative in Haifa who told her stories about her great-grandmother. “I found out about my namesake from this lady, Tirzah. She told me stories that were irreplaceable.”

Love of Jewish genealogy and history may be in Kelman’s genes. Her late brother, Sol Edell, was a dedicated amateur historian-archivist who helped establish the Ontario Jewish Archives. And nephew Yale Reisner is chief archivist of the Ronald Lauder Genealogical Project at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Nearly a quarter-century into her quest, having tracing back some ancestral lines to the 1740s, Kelman expresses amazement “that I was able to recover so much, so late, when everybody was gone.” Like many of us, she’s now faced with the formidable challenge of publishing her findings for future generations.

She flips through an impressively thick batch of papers — a partial first draft of a manuscript that she’s been working on for a long time. “I’ve put so much work into this that I want it to be preserved,” she declares. “I want it to be in a unit that you can hold in your hands.” And so, with help from Above, her labour of love continues. ♦

◊ Sarah Edell Schafler Kelman passed away in 2014.