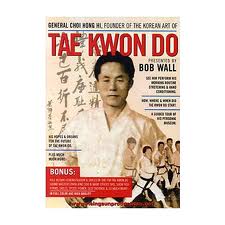

General Choi Hong Hi, who founded the martial art of taekwon-do in Korea in 1955 and devoted his life to its promotion, has died in his birthplace of Pyongyang, North Korea. He was 83.

General Choi Hong Hi, who founded the martial art of taekwon-do in Korea in 1955 and devoted his life to its promotion, has died in his birthplace of Pyongyang, North Korea. He was 83.

Gen. Choi established the International Taekwon-do Federation in 1966 and oversaw its growth into more than 100 countries. He used to say he had two names, the one his father gave him and “taekwon-do,” a word of his own coinage which means “the art of kicking and punching.”

When Korea split into North and South following the Second World War, Gen. Choi helped South Korea form an army and an intelligence agency. Rising quickly in the ranks to become a general, he participated in a military coup that installed Park Chung Hee as president in 1961. He was later forced into exile when President Park sought control of the ITF “to use as muscle for his dictatorship,” Gen. Choi would explain. He moved to Mississauga, Ont., in 1972 and became a Canadian citizen in 1977.

* General Choi Hong Hi, founder of the martial art of taekwon-do. Born November 9, 1918, in Pyungyang, Korea; died June 15, 2002 in Pyungyang.

At its height, the martial art that he established as a synthesis of ancient techniques and spiritual values had tens of millions of students worldwide. As one of two grand master IXth dan black belts, he was acclaimed not only as its founder but also as its highest-ranking practitioner.

“The General developed taekwon-do not only as a means of self-defense, but as a way of life,” said Carol Davis Hart, managing editor of the Tae Kwon Do Times, a magazine based in Bettendorf, Iowa. “It gives you a philosophy and rules of conduct to follow. The General based the conduct on what are called the five tenets of taekwon-do — courtesy, integrity, perseverance, self-control and indomitable spirit.”

To many, the gentlemanly Choi fully embodied these qualities. Standing about five feet tall, he was relatively small of stature but of unbounded stamina. Younger people who traveled with him often complained they could not keep up with him. “They would say, ‘I don’t know how your father can cross so many time zones in a week and not get sick,” said his daughter, Meeyun Colomvakos, a Toronto restaurateur. “It was because his mind was controlling his body. He was never tired, never hungry. All those things he could control with his mind because he had things to do. He had a mission to accomplish.”

To many, the gentlemanly Choi fully embodied these qualities. Standing about five feet tall, he was relatively small of stature but of unbounded stamina. Younger people who traveled with him often complained they could not keep up with him. “They would say, ‘I don’t know how your father can cross so many time zones in a week and not get sick,” said his daughter, Meeyun Colomvakos, a Toronto restaurateur. “It was because his mind was controlling his body. He was never tired, never hungry. All those things he could control with his mind because he had things to do. He had a mission to accomplish.”

He maintained his hectic pace even into his eighties, according to his friend, Jong Soo Park, director of the Jong Park Taekwon-do Institute in Toronto. “He was traveling 260 days per year to every corner of the globe. When people would ask him where he lived, he would point to the sky.”

Gen. Choi’s early life contained much adventure and danger. In 1930, as he was departing for Japan to study calligraphy, he lost all his money in a card game and flung an ink bottle at his opponent’s head. “As the ink and blood flowed down his face, I took the money from his pocket and ran home,” he would recall. When he got to Japan he began to study karate as well, attaining a black belt within two years. He also studied English and mathematics.

Since Korea was occupied by Japan, Choi was forced into the Japanese Army during the Second World War; he was caught trying to escape and was convicted of treason. Imprisoned in Pyungyang, he faced execution on August 18, 1945, but the country was liberated three days before.

During the Korean War of the early 1950s, he fought with the democratic South and once briefed U.S. General Douglas McArthur on conditions at the front lines. “No questions, very clear,” said McArthur afterwards, then asked him his name. Later he impressed many other military officials with displays of taekwon-do. “I never imagined that the human body could produce such power,” said General Tiu, a future president of Vietnam. “This is a martial art we should practice in Vietnam.”

As the ITF expanded, Gen. Choi became convinced that President Park would either place him under house arrest or throw him into jail if he did not surrender control of it. At an ITF meeting in 1971 he said, “My dear members, the International Taekwon-do Federation’s president is a Korean, but this does not mean that the ITF should be controlled or directed by the Korean government. It is an international organization that can let no country influence our decisions through undue pressure.” Soon after he was making plans to leave the country in secret.

Gen. Choi claimed that he was subject to many kidnap and assassination attempts, and that South Korean agents once kidnapped his son and daughter and threatened their lives if he did not return to Korea. “My response to them was, ‘I choose taekwon-do over my son.'” His children were released.

“He was a true grand master,” said Michael Tibollo, chief legal advisor for the ITF. “He lived what he believed, which is that you don’t do any harm to anyone and you respect everyone. He exemplified whatever you think of when you think of the old grand masters.”

Gen. Choi leaves the ITF in disarray as it faces internal battles over a successor; his son, James Choi of Mississauga, had been elected to succeed him but the vote has caused a serious rift in the organization, according to Mr. Tibollo. “Part of the problem was that Gen. Choi allowed himself to be influenced by people he should have been more cautious about” in his last days, he said.

The organization is also facing a major challenge from the rival World Taekwon-do Federation operated by South Korea. When the International Olympic Committee recognized taekwon-do as a medal sport for the first time at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, it was the WTF’s altered version of the sport that was accepted. In his final years Gen. Choi had sought to unify the two federations, but the differences between them were reportedly as glaring and insurmountable as those between the two Koreas.

Afflicted with stomach cancer, he returned to North Korea in May and died June 15, surrounded by family and friends; he was buried in a patriarch’s tomb. He leaves his wife Chun Hi, son James, daughters Meeyun and Sunny and several grandchildren in southern Ontario, and several surviving brothers and sisters in North Korea. ♦

© 2002