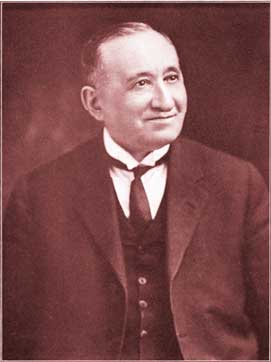

THE following feature profile of Jacob Cohen, a retired Toronto businessman who became Toronto’s first Jewish justice of the peace in 1907, appeared in the Toronto Globe of March 12, 1910.

THE following feature profile of Jacob Cohen, a retired Toronto businessman who became Toronto’s first Jewish justice of the peace in 1907, appeared in the Toronto Globe of March 12, 1910.

* * *

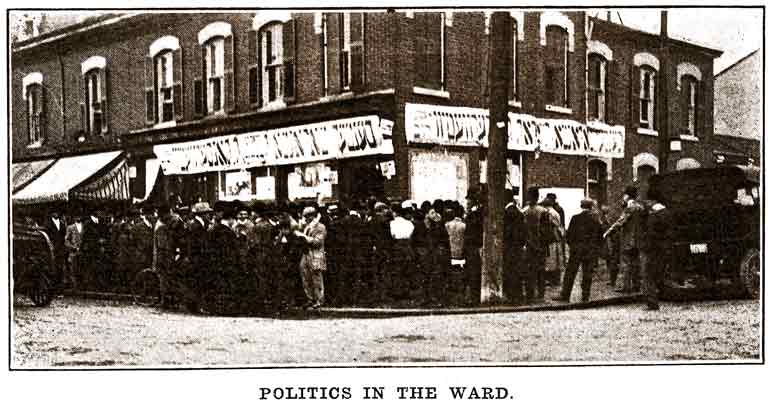

SNUGLY settled in the heart of Toronto reposes a little Hebrew nation sixteen thousand strong and growing rapidly. It has its own ideals, its own language and its own age-old customs. It has its own leaders, too. Like those “able men fearing God, men of truth, hating covetousness,” whom Moses designated to sit in the gates of the cities and hear complaints and grievances, it has its rabbis and civil leaders to whom these modern children of Moses go with their troubles. A litigious people they are by nature, and few outsiders know how much work the courts are spared by the mediation of their rabbis and prominent men. The instruction “In every small matter they shall judge” seems still to hold true.

No one man in Toronto’s Jewish colony has done more to earn the rewards of the peacemaker than Mr. Jacob Cohen, J. P. The Justiceship of the Peace bestowed upon him three years ago by the Government was never more fittingly awarded or more well deserved. To adjudicate the partnership difficulties of three sets of rag and bottle dealers, reunite four estranged pairs of husbands and wives, interview and warn a couple of erring spouses, hand out advice to several tearful and love-lorn Jewish maidens, examine the stories of half a dozen applicants for charity, find jobs for a brace of new arrivals from Europe, collect funds to aid some unfortunate co-reigionist, and then preside at some social, political or charitable meeting in “The Ward” at night is a mild day’s work for Mr. Cohen.

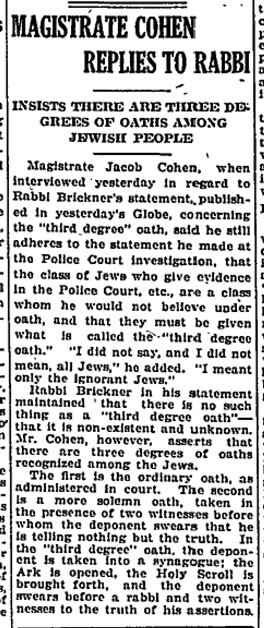

Daily his services as an interpreter and as a judge of Hebrew character are in demand in the Police Court, where on occasions he presides as Magistrate. A whole host of activities crowd one another on the useful life of this sunny-faced little man. Were he paid fees for all the work he does he would probably be grumbling about overwork. But Mr. Cohen, being a gentleman of independent means, works cheerfully all day long and refuses even such pecvuniary rewards as his office entitles him to. “The happiest man in Toronto,” was the accusation once charged against him, and “Jakey,” as he is popularly called, did not deny the charge.

Sometimes the little man drops his cloak of jocularity and confides, “I do this for my people, because they are so ignorant. They have been used to persecution. They have had no rights. This liberty they have is too much for them at first. It seems so good to them that the law gives them rights that they want to go to law to see if it is true. And then my people have always among themselves appealed to the law.”

“Adjourn this case for a week and ask Mr. Cohen to find out what’s at the bottom of it,” is a pronouncement heard in the Police Court when the Magistrate is in doubt in a case between two Hebrew citizens. For “Jakey” knows the subtle workings of the Jewish mind. He is one of the people.

This modern Judge in Israel has risen to his present honorable place from being a poor immigrant boy. Sixty-two yhears ago he was born in Cracow, Austria. Yearning for the freedom he had heard of in the west, he left home as a boy of fourteen and got a passage to New York. Knowing scarcely a word of English, the enterprising lad set out with a little peddler’s pack through the farming districts. At sixteen he went to New Orleans, where the steamboat captains on the Mississippi got to know the little birght-eyed Jewish boy.

Those were adventurous times coming just after the civil war, and when a compatriot in Chicago told him of the English country to the north, and how well some of their race were respected in a city called Toronto, he decided to visit this place. That was in 1872.

A little store on Queen street, within shadow of where the City Hall now stands, rented for $4 a month, gave him his start in business. Now the little boy peddler can boast of an honor from the Government, is an ex-President of the Holy Blossom Synagogue, Treasurer of the Jewish Benevolent Society, President of the Cosmopolitan Club, and honorary agent of the Israelitish Colonization Association of Paris, the society to which Baron de Hirsch donated his fortune, and has held many positions of honor in the Oddfellows’, Foresters’, and Masonic Lodges.

He has the unique honor of being the first Hebrew to hold Magistrate’s court in Toronto, where he has frequently been commended by the Bench for valuable services.

A substantial rumor has it that “Jakey” dictates the Hebrew vote in Toronto, usually in the interests of the Conservative party, but he smiles and shakes his head enigmatically at the charge. A collection of silk hats — and “Jakey” wears no other variety — testifies to his skill in picking winners at election time. His clean-shaven face tells of his allegiance to the “Young Hebrew,” or “Progressive,” party.

Hundreds of stories are told about Mr. Cohen, some of which may not be true. His informal court held in the corridors of the City Hall each morning is one of the most amusing and withal most useful of functions. It is averitable Cave of Adullam for the disconsolate of Israel. One incident is typical of many. A pushcart man greatly excited burst in, gasping out his need of advice. His cart had been grazed by an automobile and a bicycle dragged off the top of the load. He wanted advice how to sue the auto-owner for $10 damages.

“I joost hav’ giv’ six dolalrs for der bike, an’ four dollars to men’ der vaggon,” declaimed the Hebrew.

“Get back to your work and tell no more lies,” ordered the Squire. “Six dollars? You know very well some woman gave you ten cents to take it away.”

Away went the man, quite satisflied. He had got the judgment of “Judge Cohen,” and some overworked Magistrate was saved the task of listening to a tribe of hopelessly cotradictory witnesses.

The reverence some of these men have for the law and its appurtenances is scarcely believable. One man, who, with his Russian cap, bearded face, top boots and whip in hand, looked a typical Russian moujik, came seeking advice a few weeks ago. Five reporters struggling to produce live copy were the sole occupants of the Police Court. With a series of bows and abasements, the man approached to ask for Mr. Cohen. He literally trembled as he addressed the august occupants of the press gallery. The Supreme Court Bench could hardly hope to inspire more awe. As he withdrew he paced slowly backwards, and at the door of the court made five profound bows — one apiece for the reporters.

The reverence some of these men have for the law and its appurtenances is scarcely believable. One man, who, with his Russian cap, bearded face, top boots and whip in hand, looked a typical Russian moujik, came seeking advice a few weeks ago. Five reporters struggling to produce live copy were the sole occupants of the Police Court. With a series of bows and abasements, the man approached to ask for Mr. Cohen. He literally trembled as he addressed the august occupants of the press gallery. The Supreme Court Bench could hardly hope to inspire more awe. As he withdrew he paced slowly backwards, and at the door of the court made five profound bows — one apiece for the reporters.

Yet it is of such material that Mr. Cohen and other of his co-religionists are making good Canadian citizens. “I won’t get you no scond-hand license — go and work at some clean, useful business and become a good Canadian,” is advice he gives very often, for the Jewish leaders in Toronto are trying to educate their people away from the rag and bottle ideas of commerce, and the policy is showing its fruits in the younger generation.

Many of the latter are forsaking commerce entirely and are entering the professions by way of the University of Toronto. Most convincing proof of all is a visit to the Cosmopolitan Club — the old Dalton McCarthy residence on Beverley street.

There on the splendid lawn of a summer’s night, beneath the light of Chinese lanterns, standing within the shadows of the trees, or dancing to the tune of an orchestra, one may see the second generation of Toronto’s Hebrew colony. The men, for the most part, are clean-shaven and alert, the women well-gowned and good to look at, and all with an air of prosperity and social worth.

But “Jakey” is more than a dispenser of good advice or a doler out of other people’s charity. Many a poor prisoner with a pitiful tale to tell — Jew and Gentile alike — has had his or her fine paid and a fresh start given them by the big-hearted little Squire. Many a poor family with their goods seized by the bailiffs have had their debts paid and the bailiffs ordered out by the little Jewish J. P.

“I get more fun spending my money and my time like this than if I’d stayed in business,” is strange philosophy to fall from the lips of a retired Jewish tradesman. Stranger wtill when one reflects that his views on life and citizenship were formed, not in some university away from the struggle of life, but in the heart of a homeless boy peddler tramping his way through a strange land. — J.S.C. ♦