Fingerprints Practically Infallible — Inspector Duncan an Expert at Identification — A Card With a Peculiar History — How Prisoners Behave Before the Camera

By Leo Devaney

From The Toronto Star Weekly, January 17, 1914

Probably the most important and yet the least known department of Toronto’s police system is the identification bureau, where the records, fingerprints, photographs and measurements of criminals are kept.

Probably the most important and yet the least known department of Toronto’s police system is the identification bureau, where the records, fingerprints, photographs and measurements of criminals are kept.

In one small room situated next door to the Detective Department at the City Hall there are the records and descriptions of over 10,000 criminals gathered in by the Police Department in the last twenty or thirty years.

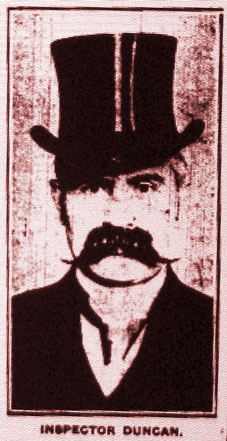

The man who has charge of this department, Hugh Duncan, is a man almost invaluable to the Police Department. The possessor of a good memory and a keen eye, it is only once in a great while that he fails to identify any person who has ever been before him.

When a man is arrested, suspected of some crime, he is brought to the detective office. Later, he goes before Mr. Duncan, who looks him over carefully and decides whether his photo is among that tidy little bunch of exhibits known as the Rogues’ Gallery.

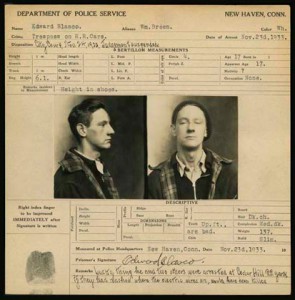

Should he be a new man to the Police Department, he is taken upstairs and two photographs made of him. One picture shows the face from a side view while the other shows the man facing the camera.

After his picture has been taken he is stripped and is measured by the Bertillon system. The length of his arm, his head measurement, and all other measurements are taken. Then his finger prints are noted.

How Prints are Taken

This is probably the most interesting part of Mr. Duncan’s work. A sheet of glass over which a thin layer of printers’ ink has been spread is prepared and the criminal has his fingers impressed in the ink, after which the wet fingers are pressed on to an ordinary sheet of paper. The finger prints, the photograph, and the measurements are all numbered and are transferred into several books. They are available at a few moments’ notice.

The question has been asked that if a man whose finger-prints have been taken by the police should burn or scar the “palm” of the fingers with acid or by any other means would the Police Department be able to identify the man by a new impress of his fingers. Mr. Duncan explained that if the fingers have been recently burned or scarred he would be unable to tell from the finger-prints whether the man had ever been up before, but that if a short time had elapsed between the time the fingers had been burned and the appearance of the man in the identification bureau the skin would have healed sufficiently to allow the natural lines, the little whirls, and circles, to appear again. No matter how many times the fingers have been burned or scarred the original lines will reappear just as soon as the skin heals.

Head Measurement

With the exception of the finger-print system, the system of head measurement is probably the most reliable in existence. The three principal parts which are measured are the head length, head width, and cheek width. After a man is fully developed these measurements to not change, and there are no two men with exactly the same head measurements.

All these measurements go into a book and are later transferred to a card. On this card appears the name of the prisoner, date of conviction, description, chare, sentence, and who the detective was in the case. The card system extends over a period of 25 years. The average number of criminals who undergo this system of measurement, and whose photographs are taken, is about 700 each year. This means that 700 men who have committed indictable offences each year and who have been convicted leave their records in the identification bureau.

While the number seems small for a city the size of Toronto, it must be remembered that each year there are a number of prisoners which the police department classifies as “repeaters” — that is, men who, after they have served their sentence, are caught on some other charge and convicted. In the case of these “repeaters,” their photographs are measurements are not taken again. The card bearing their name, records and description is taken out and the last charge, date, and sentence added to it.

A Life Behind the Bars.

There is one card in the identification bureau that has a peculiar history. Inscribed on this card are 41 convictions for one man. This man has the distinction of having the longest record of many that ever came into the police department. He is over 60 years of age now, but the date of his first crime was over 40 years ago. In those days he was a strong, healthy young man with lots of nerve, and no mean amount of skill, as the nature of his crimes will testify.

There is one card in the identification bureau that has a peculiar history. Inscribed on this card are 41 convictions for one man. This man has the distinction of having the longest record of many that ever came into the police department. He is over 60 years of age now, but the date of his first crime was over 40 years ago. In those days he was a strong, healthy young man with lots of nerve, and no mean amount of skill, as the nature of his crimes will testify.

Daring cases of burglary, housebreaking, and highway robbery are all credited to him. It is safe to estimate that this man has spent easily two-thirds of his life behind stone walls. His first twenty years of crime comprise many reckless deeds. This man in those days took all kinds of chances. He was young, he had not felt the hand of the law often enough to realize its power, its relentlessness, and he has unbounded confidence in himself.

After he had been caught a couple of times, the cards show a lot more time between his convictions. He has grown more wary, also his criminal deeds less daring. He confined himself a number of years to commit smaller crimes with less chance of detection. The arm of the law is long, however, and though he may have escaped punishment for a number of crimes, the law eventually caught up with him.

When he had passed the fortieth milestone of his life, his crimes became more and more mean. He was thieving from department stores, stealing umbrellas out of hallways, and similar little thefts. . . . (illegible).

The last time he was sentenced was for the theft of a lawn-mower. Two score years ago he would have probably ridiculed the man who would have suggested the theft of a lawn-mower or an umbrella, but the spirit he had then, years ago, has been pretty well removed out of him, and the crimes that he committed in the heyday of his youth now look desperate to him. He steals now, more to keep alive than anything else.

Attitude of Prisoners

This is but the case one man whom the law, while it has tamed him, has subdued. Other tales there are of men, while their records are not so long, suggest that they mapped out for themselves a career in crime.

The attitude of these criminals as they stand before the camera preparatory to having their picture placed in the Rogues Gallery is interesting. For their first offence, and the crime has been a daring one, the man often seems ill at ease, nervous, and hesitates. But smaller fry, the pickpocket and penny thief, are generally filled with bravado and talk incessantly, while the big criminal, the man who might have his picture in a dozen Rogues’ Galleries, is a cool, unconcerned and incommunicative individual. He is calm before the camera, as if it was an everyday occurrence.

Considerable discussion has occurred as to the ability of trained detectives to read another’s character by his appearance, the study of his physical peculiarities. That this is not a workable theory is the opinion of Mr. Duncan, who has handled thousands of cases, and should know. While he admits that a man’s life leaves its imprint upon him, he declares that it is impossible from a man’s appearance to determine whether he is criminally inclined or not.

A good deal has been written about the man who looks like a criminal, with shifty eyes, the weak chin, etcetera, but they are not indications of his moral character. The honest, clean, straightforward-appearing man many turn out to be the most daring of criminals. Two New York criminals who were sent back to long terms in the United States were fine-looking young men. One looked like an up-to-date business man, while the other might have been taken for a college professor. A strange contrast was the appearance of one of the American officers who arrived to take them back. He was tall and slim, with weak eyes too close together, and a profile like many seen in a criminal record. One might easily have been forgiven if he picked out the police officer as the criminal and the criminal as the officer of the law. ♦