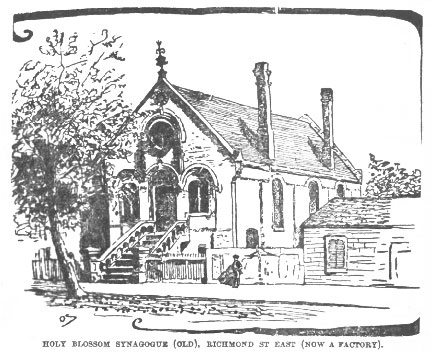

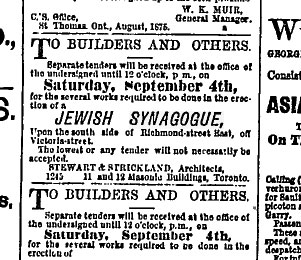

Note: This very early article may be the first significant piece written about the Jewish community of Toronto and any of its synagogues. It appeared only six years after the synagogue was built in 1875 on Richmond and Victoria streets. Like many stories of its kind from that era, it treated the Jews in a kindly fashion, colouring them as an exotic tribe full of “oriental” strangeness yet possessed of fine traits — such as learning, a predominant tendency to be law-abiding, and a loyalty towards their faith — that were admirable and deserving of respect. Here is Toronto, this most British and Anglo-Saxon of cities, beginning to take notice of the slowly growing community of Jews in its midst. At the time, the Richmond street synagogue was the only Jewish house of prayer in Toronto; however, another minyan had just been established in that year and would coalesce and merge into Goel Tzedek within a couple of years. The illustrations are from the book “Landmarks of Toronto (1901); the ad below appeared in The Globe on August 30, 1875. — B.G.

How the Day of Atonement is Observed by the Jews in Toronto

The Synagogue Services

A Weird Ceremonial and a Strange Mixture of Ancient and Modern Costumes

From The Toronto Globe, October 3, 1881

Yesterday evening at sunset the Jewish day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, began and the Synagogue on Richmond street was filled with an assemblage of Hebrews belonging to the city with strangers from inland towns and from the country, as well as travellers who found Toronto a convenient place in which to spend the important day.

Yesterday evening at sunset the Jewish day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, began and the Synagogue on Richmond street was filled with an assemblage of Hebrews belonging to the city with strangers from inland towns and from the country, as well as travellers who found Toronto a convenient place in which to spend the important day.

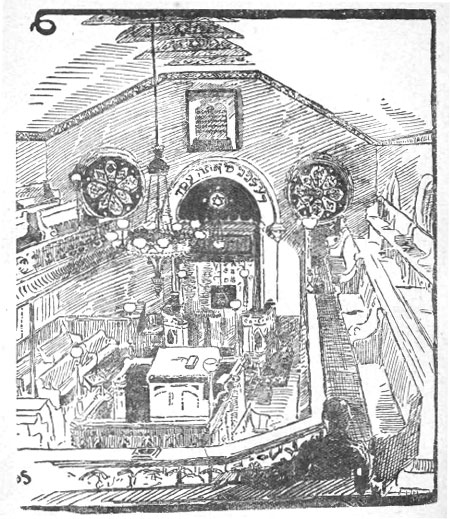

A strange service lasting for three hours commenced. The men occupied the body of the synagogue, and in the gallery above the lobby were the women. At the end of the hall opposite the gallery is a platform reached by steps, and at the rear of it, in an arched recess excluded from view by doors overhung with a white curtain bearing the inscription in Hebrew, ‘There is but one God,” is the Ark of the Covenant containing the Torah, or Pentateuch, written on parchment.

Around the arch above is the inscription, in Hebrew, “For whom doest thou stand ?” and over it, also in Hebrew, the Ten Commandments. In the centre of the hall is a somewhat extensive platform, enclosed on its four sides by a framework three feet high, and enclosing the reading desk covered with a white fabric. Four tall brass “candlesticks” for the gas jets stand on the railing or framework referred to. The benches are ranged around the reading desk platform. No organ or musical instrument is used, and apart from the ornamentation referred to, the ball is comparatively plain.

The Audience.

The ladies in the gallery were dressed in their usual costume, nothing remarkable being noticeable excepting the greater frequency of white dresses than on ordinary occasions. Among the men there was a strange blending of ancient and modern dress, and a weirdness in the costumes and ceremonial that could not but fascinate a stranger. The Rabbi in the reading desk was dressed in a long white gown, resembling neither a Roman toga nor an Anglican surplice. Over his shoulders was flung a white, shawl-like garment called the Thalis, and along the outer margin, which drooped over his arms in front, were several bands of black. On his head was a round white cap swelling out as the flat top was approached.

A Strange Blending.

In the congregation were many similarly dressed, and their ancient faces and patriarchal grey beards vividly suggested the men of the olden times when the temple service was yet in its glory. Some had the thalis drawn over their heads, and their bent forms, as they swayed to and fro during the incantations, bowing low every now and then, as they wailed out the peculiar melody, and beat their breasts every now and then, added to the oriental and ancient features of the scene. The nineteenth century and the fashions of Paris were alongside of those picturesque figures, and formed a striking contrast. Most of the men were dressed in black broadcloth of the most approved cut and style, and wore tall silk hats. Over the black coat was elegantly thrown the loosely flowing thalis. Many of the ancient and modernly dressed worshippers were in their stocking feet, a custom which is regarded by some as more significant of respect to the character and object of their worship.

The Services.

The services last night consisted almost entirely of prayers from the liturgy — a copy of which was in the hands of every person — the Hebrew text on one page, and a German or English translation on the page opposite, and the pages numbered from the back of the book forward. Early in the evening the Rabbi, Dr. Gluck, addressed the congregation in German on the significance of the day and its ceremonies, and sought to impress on all the importance of heartfelt love to God and charity and righteous conduct between man and man. The ceremonies were weird and impressive.

The services last night consisted almost entirely of prayers from the liturgy — a copy of which was in the hands of every person — the Hebrew text on one page, and a German or English translation on the page opposite, and the pages numbered from the back of the book forward. Early in the evening the Rabbi, Dr. Gluck, addressed the congregation in German on the significance of the day and its ceremonies, and sought to impress on all the importance of heartfelt love to God and charity and righteous conduct between man and man. The ceremonies were weird and impressive.

Weird Chanting.

The Rabbi, in a loud voice, chanted in a strange and peculiar manner, unknown in the Roman, Greek, or Anglican Churches. Often before he closed his parts the responses of the congregation strangely mingle with his utterances. The responses were apparently chanted, intoned, or read, according to the liking of the individual. There was no attempt at tune, nothing but an intermingling of various and discordant voices, as of a multitude, each member of which was supplicating for himself.

Yet it was impressive, and through it all ran a vein of sadness, the very melodies reflecting the long, sad history of the chosen race. A few of the men stood during the whole service: the others rose and sat down at frequent intervals. On the opening of the ark, which occurred several times, every one rose, and on its closing sat down. The prayers were full of confession of sin, and a vast variety, of violations in act and spirit of the law of God were particularized.

In pleading for forgiveness, the memory of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and the ancient Jewish worthies was dwelt upon. At the close several members of the congregation entered the reading desk separately and led in prayers, the congregation joining every minute. At the close several hymns were chanted in a pleasing manner. Then the thalis, which must be either of pure silk or pure wool — in Mosaic times it was of lamb’s skin — was taken off, folded up, and either placed in a small ornamented silk bag to be carried home or laid over the back of the wearer’s pew.

In pleading for forgiveness, the memory of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and the ancient Jewish worthies was dwelt upon. At the close several members of the congregation entered the reading desk separately and led in prayers, the congregation joining every minute. At the close several hymns were chanted in a pleasing manner. Then the thalis, which must be either of pure silk or pure wool — in Mosaic times it was of lamb’s skin — was taken off, folded up, and either placed in a small ornamented silk bag to be carried home or laid over the back of the wearer’s pew.

Today’s Proceedings.

The day thus commenced is strictly observed. No work whatever is down for twenty-four hours; not a match will be struck, and not a lamp or gas jet lighted. before sunset yesterday every light necessary was burning, and not one of them will be put out till after sunset this evening. A rigorous fast will be maintained, eating, drinking, and even smoking being totally avoided. The people will remain assembled in the synagogue from six this morning till sunset, engaged in prayer, praise, and the reading of the parchment roll kept in the ark. At sunset the trumpet will sound, and the great day of atonement will be over. ♦