An intriguing collection of essays throws a new light into the dark world of the Jewish ghettos of Eastern Europe as seen by a cavalcade of Jewish writers including Heinrich Heine and Joseph Roth, and numerous others who have been all but forgotten.

An intriguing collection of essays throws a new light into the dark world of the Jewish ghettos of Eastern Europe as seen by a cavalcade of Jewish writers including Heinrich Heine and Joseph Roth, and numerous others who have been all but forgotten.

Ghetto Writing: Traditional and Eastern Jewry in German-Jewish Literature from Heine to Hilsenrath, edited by Anne Fuchs and Florian Krobb (Camden House, Ireland) offers a pioneering look into this rich subcategory of literature, which for the most part remains untranslated into English.

Remarkably, the book was prepared entirely outside of Germany by two scholars, Anne Fuchs and Florian Krobb, attached to universities in Dublin, Ireland. Its 14 essays were contributed by critics in Scandinavia, Germany, Great Britain and Ireland. Commendably, Fuchs and Krobb rendered all cited literary quotations into English, thus providing English-speaking readers with an insightful glimpse into this important but obscure body of work.

In an introduction, Fuchs and Krobb identify and fix the date of the first true piece of ghetto writing. It is Aus dem Ghetto — From the Ghetto, Leopold Kompert’s collection of stories about life behind ghetto walls, which appeared in 1848.

Publishing their anthology on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Kompert’s collection, the editors acknowledge many instances of “ghetto writing” occurring decades before Kompert, but assert that he was the first to put the ghetto setting into a universal literary context and use it as a metaphorical model to treat issues related to Jewish identity and emancipation.

In one Kompert story, “Outside the Ghetto”, he describes the exhilarating feeling of escaping, albeit momentarily, from the confined space into which all of Jewish society had been crammed. It is a first-person reminiscence of how the narrator, as a boy, ran up the hill above the Judengasse, against the advice of family members, and experienced a dizzying sense of freedom:

“They had warned me, they had urged me not to go, not to take this dangerous path up the mountain; but I had laughed at them and said: Let me go! and now I stood up there. My grandmother is wringing her hands in anguish towards me, I can hear a cry depart from her lips, and my grandfather is wagging his finger and shaking his head thoughtfully.”

“They had warned me, they had urged me not to go, not to take this dangerous path up the mountain; but I had laughed at them and said: Let me go! and now I stood up there. My grandmother is wringing her hands in anguish towards me, I can hear a cry depart from her lips, and my grandfather is wagging his finger and shaking his head thoughtfully.”

Repeatedly, Kompert seems to be looking back on the ghetto from a sentimental position of exteriority. This nostalgic, romanticized stance is one of two main polarized views that contemporaneous writers had of the ghetto. The other view, steeped in modern realism, highlights the crowding, stench, dirt, lack of sunlight and other squalid conditions.

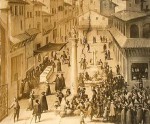

In his essay, “The Frankfurt Judengasse in Eyewitness Accounts from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century, “ Eoin Bourke offers an extraordinary set of views of the infamous Frankfurt ghetto, formerly one of Europe’s most vertical and densely crowded pieces of real estate. According to some (non-Jewish) observers, the Jews deserved no better than the inhumane conditions under which they were forced to live.

“The more they feel locked in and sit on top of each other, the better they propagate: the place is creeping and crawling with Hebrew figures,” writes one hostile observer. “To the question of how this ancient remainder of the twelve Israelite tribes nourishes itself, the answer is by fraud.”

Other observers are more sympathetic, seeing the dejected condition of the ghetto Jews as an indictment of the antisemitic attitudes of the majority. “That,” notes one writer, “is our Christian way of treating a people who have the same human right to freedom as we have, from whom we are descended, so to speak, who have preserved more originality, uniqueness and purity of morals than we, and whom we now force to live from usury by thwarting every possibility of an alternative means of living in the most dishonorable way.”

It is precisely this attitude that informed the earliest pro-emancipation writings of Dohm and other civil libertarians, who campaigned for full civil rights for the Jews.

Ghetto Writing offers a scintillating glimpse of a literary treasure-trove. Works examined include Wilhelm Jensen’s 1869 novel The Jews of Cologne, Joseph Roth’s 1927 novel Jews On Their Wanderings, Herz Wolf Katz’s 1937 novel The Fishmanns, Alexander Granach’s 1945 autobiographical novel There Goes An Actor, and works by Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Edgar Hilsenrath. There’s even a study of Zionist images from the journal Die Welt, which Theodor Herzl edited.

The final essay, which focuses on ghetto imagery in modern punk and rap culture, brings the collection right up into the 1990s. The ghettos and shtetls of yesterday are no more, but their memory and meaning evidently live on, transformed and renewed by Western pop culture. ♦

© 1999