December 10, 2025

Librarians are a cautious bunch. How else to explain why those at the main branch of the Toronto Public Library have taken to hiding away the latest Toronto phone books from public view?

Librarians are a cautious bunch. How else to explain why those at the main branch of the Toronto Public Library have taken to hiding away the latest Toronto phone books from public view?

They are all on the open shelf, they will tell you. But they are not. The phone books on the open shelf go up to 2009 and no further.

At first the librarian deflected my specific request for more recent volumes, but my genealogist’s instinct told me I was being gaslighted. I asked again, more pointedly than before, if they had more recent volumes.

To the best of my recollection, our conversation went something like the following:

“What are you trying to do?”

“I’m trying to trace a missing person.”

“For what purpose?”

“To find their current whereabouts.”

She was looking up other potential sources on her computer; the dialogue continued.

“When was the last time you saw this person?”

“I’ve never seen them at all. I’ve been hired to try to find them.”

“What for?”

“I don’t even know – they didn’t tell me. But cases of this kind usually involve estates.”

“And what is the name of the person?”

“I’m sorry, I can’t tell you that!”

After a few more questions of this sort, I handed the librarian my professional card which she looked at with interest. It apparently transformed her instantly into an ally. She finally admitted that yes, the library does indeed hold more recent volumes. They were generally not offered to patrons, however, because there was a perception that they posed a challenge to modern standards of privacy.

I countered that the books were already in the public domain by virtue of the fact that they had been published and massive numbers of copies circulated. I might have added that all listings were a matter of consent, the removal of which caused numbers to be unlisted.

Like a bootlegger pulling out a bottle from behind the counter, the librarian eventually opened a small drawer behind her and pulled out several thin directories from 2021 to 2023. After I looked at those useful books, she helpfully offered to retrieve more books of recent vintage from a back “annex.”

True, the phone book has been on the endangered species list for decades and, like the dinosaur and once-ubiquitous city directory, has now pretty much gone extinct. Those that remain are but thin shadows of their former incarnations. The remaining volumes, those we can coerce from their secret hiding places, are essentially the last of their breed.

True, the phone book has been on the endangered species list for decades and, like the dinosaur and once-ubiquitous city directory, has now pretty much gone extinct. Those that remain are but thin shadows of their former incarnations. The remaining volumes, those we can coerce from their secret hiding places, are essentially the last of their breed.

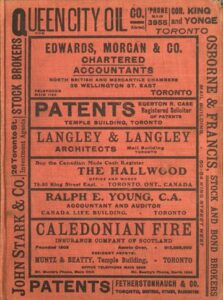

The first phone books appeared in the 1870s, a few years after the telephone itself. By 1910, American and Canadian telephone books were tracking more than seven million numbers. Toronto’s first city directories appeared in the 1830s, shortly after the city’s founding, and were published annually until about 2001 when the final volumes appeared.

Both resources remain a gold mine for researchers but, sadly, both have declined precipitously since the turn of the 21st century, having fallen off the proverbial cliff once the web and smartphones became universal.

TPL has fully digitalized the entire run of city directories and many — excepting the more recent years — are freely available online. Ancestry, MyHeritage, the Internet Archives, FamilySearch and other websites now offer somewhere between 500 million and a billion searchable directory pages. Hard copies are also available at the City of Toronto Archives, but only until 2001.

For genealogists and local historians, this is an awesome gain in terms of convenience and ease of use. But the disappearance of these powerful tools from our collective genealogical toolbox leaves a gaping hole.

Sadly for genealogists, the era of telephone books and city directories has irretrievably passed. In a society beset with massive telephone fraud, identity theft, robocalls and data-scraping bots, there is little public appetite for a single, central registry of cell phone numbers. That concept, except for private and guarded registries and data-bases controlled by the government, is “gone with the wind.” ♦