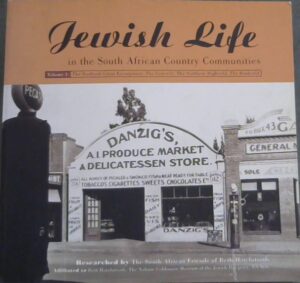

Jewish Life in the South African Country Communities. Large format, five volume set. Researched by the South African Friends of Beth Hatefutsoth.

Through some diligent genealogical detective work about a dozen years ago, I located a distant cousin in Johannesburg, descended from my grandfather’s uncle who had gone to South Africa in the WWI era. But the discovery was ultimately disappointing. I sent my newfound cousin an exuberant letter full of family lore and received in reply a polite Rosh Hashanah card with a note of thanks but not a word of family history.

After that, I put my South African research on ice — until recently, that is, when I had occasion to explore the rich history of the South African Jewish community through perusal of these handsomely illustrated volumes cataloguing the Jewish experience in South Africa. Concisely written by a team of researchers with another team collecting photographs, each of the volumes in this projected series of five books focuses on select regions and the Jewish communities therein.

Volume 1 (2002) is titled The Northern Great Escarpment, The Lowveld, The Northern Highveld, The Bushveld; it details Jewish life in 37 country towns. Volume 2 (2004) provides information on more than 70 country towns in the Western & Northern Cape and the territories of Boland, Bushmanland, Central Karoo, Fairest Cape, Griqualand West, Kalahari Koup, Namaqualand, Swartland, West Coast. Volume 3 (2007) focuses on Camdeboo, Cape Midlands, Garden Route, Langkloof, Little Karoo, North-Eastern Cape, Overberg, Settler Country, Transkei, and Griqualand East.

The two volumes focus on the Orange Free State and Natal.

Many of these place names will sound as foreign and exotic to many readers as phrases like Shmah Yisroel, gefilte fish, borei pree hagafen, kreplach and motzei lechem min ha’aretz might sound to the non-Jewish residents of these places. And yet some of the residents bore such familiar surnames as Blumberg, Cohen, Edelstein, Fineberg, Gershowitz, Kaplan, Rosenberg and Shapiro.

Many of these place names will sound as foreign and exotic to many readers as phrases like Shmah Yisroel, gefilte fish, borei pree hagafen, kreplach and motzei lechem min ha’aretz might sound to the non-Jewish residents of these places. And yet some of the residents bore such familiar surnames as Blumberg, Cohen, Edelstein, Fineberg, Gershowitz, Kaplan, Rosenberg and Shapiro.

The extent to which Jews once settled the remote South African countryside seems remarkable. Equally remarkable is the fact that for many of these remote places, the books offer comprehensive lists of families that once lived there, and a capsule history of the Jewish presence in each place. There are also photographs on nearly every page of old synagogues, prominent citizens, family and community gatherings, hotels and main streets, farmers and settlers on horseback.

The researchers visited major libraries and archives as well as smaller research facilities all over South Africa. They also conducted oral interviews with many present and past residents and used the proverbial fine-tooth comb to search the back issues of the London Jewish Chronicle and other historic papers for relevant items. “The aim of this research,” they write, “is to have a permanent record of the Jewish communities in the dorps [country towns] of South Africa.”

Today most of South Africa’s roughly 80,000 Jews (down from nearly 120,000 in 1980) live in Johannesburg and Cape Town, with almost none left in the small towns and the vast and rugged countryside. The first Jews arrived in the 1820s with an influx of British settlers and their communities grew slowly until the discovery of diamonds in 1869 and gold in 1886. Many thousands of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived over the next half century and spread far and wide across the country.

Perhaps the story of Jewish country life still has such resonance among today’s city dwellers because it invokes a time when, through the mere fact of their being found in nearly every town and drop, Jews were far more connected with the country as a whole than they are today,” senior researcher David Saks wrote in a Foreword to Volume 2. “South African Jewry is now essentially a two-city community, with 85% of the total living in either Johannesburg or Cape Town and most of the remainder in Durban or Pretoria.”

South African Jews and their descendants, who may have moved to Israel and major cities in Canada and the United States in recent decades, will find these volumes a valuable and intriguing record of a vanished past. ♦

Originally published in Avotaynu, 2010

Jewish Migration to South Africa: Passenger Lists from the UK. Two large-format volumes, edited by Saul Issroff. Volume 1: 1890 to 1905. Volume 2: 1906 to 1930.

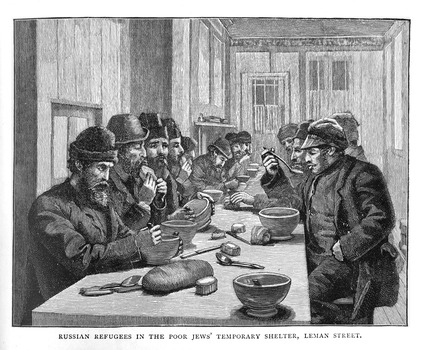

These two volumes offer extracts from passenger lists of “aliens” — non-British residents who are mostly (but not exclusively) Jewish. As Issroff explains in an introduction, the present South African Jewish community consists of people with Litvak ancestry who traveled to South Africa between 1881 and 1914. Many of these East Europeans passed through British ports en route to the southern tip of Africa.

“The journey to the arrival ports of Hull, Grimsby or London usually took 3 to 5 days depending on where they had embarked,” Issroff writes. “From the point of entry they usually went to the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter in the east end of London where they awaited the next steamship to the Cape.”

Issroff is also editor of Jewish Migration to South Africa: The Records of the Poor Jews Temporary Shelter, 1885-1914, which could be used in conjunction with these volumes to help pinpoint an ancestors’ journey and potentially find clues about their birth dates, occupations and family members. ♦