Trying to put a yarmulke on the King of rock ‘n’ roll

From the Forward, 2002

Evan Popoff, co-producer of a new documentary that demonstrates beyond any reasonable doubt that American rock idol Elvis Presley was Jewish according to halakha or Jewish law, says that the film uses Elvis “as a metaphor for identity — I think it’s a quest film about Jewish identity.”

Evan Popoff, co-producer of a new documentary that demonstrates beyond any reasonable doubt that American rock idol Elvis Presley was Jewish according to halakha or Jewish law, says that the film uses Elvis “as a metaphor for identity — I think it’s a quest film about Jewish identity.”

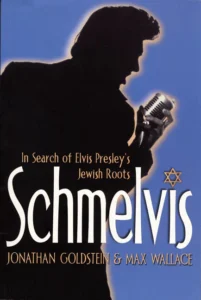

Titled Schmelvis: Searching For The King’s Jewish Roots, the feature documentary is slated to premiere at the opening of the Toronto Jewish Film Festival and may go into U.S. theatrical release later this year.

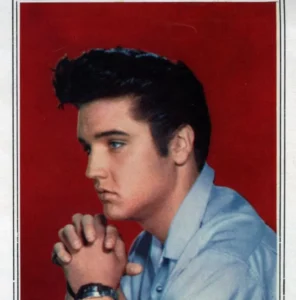

It is not clear whether Elvis, who died in 1977, ever really knew that his maternal great-great-grandmother, Nancy Burdine Tackett, was Jewish, or understood the halakhic principle of matrilinear descent through which he would have been identified as a Jew.

But he was unquestionably aware of some sort of familial Jewish connection. Although he was a practising Christian, he seemed philosemitic to the point of wearing a golden Chai around his neck and a kitschy wristwatch that alternatingly flashed a Jewish star and a Christian cross. As the film reveals, he even put a Magen David on his mother’s tombstone; it was later removed by officials of his Graceland estate.

Schmelvis offers many such revelations, including the facts that Presley, as a teenager, had Orthodox Jewish neighbors for whom he acted as “Shabbes goy”; that he once made a $150,000 donation to a Memphis Jewish charity; and that he enjoyed warm relations with many Jews, including his doctor and his tailor, Bernard Lansky. “I was clothier to the King,” Lansky boasts. “I put his first suit and his last suit on. I made him sharp. I made him what he was.”

Schmelvis offers many such revelations, including the facts that Presley, as a teenager, had Orthodox Jewish neighbors for whom he acted as “Shabbes goy”; that he once made a $150,000 donation to a Memphis Jewish charity; and that he enjoyed warm relations with many Jews, including his doctor and his tailor, Bernard Lansky. “I was clothier to the King,” Lansky boasts. “I put his first suit and his last suit on. I made him sharp. I made him what he was.”

Popoff says he got the idea for the film from a 1998 Wall Street Journal article about Presley’s Jewish roots, and soon enlisted the aid of co-producer Ari Cohen and writer-director Max Wallace. “We took one of the biggest Christian pop icons in our culture and we were able to show how Jewish culture informed his life,” says the 32-year-old Montreal filmmaker.

Schmelvis is anything but a traditional film documentary; indeed, it seems more about the filmmakers than their chosen subject. As viewers will quickly discern, it’s a film about the making of a film — and one that seems freighted with a rather ponderous thesis. Should we care if Elvis was Jewish? Is it significant?

The filmmakers wrestle indeterminately with exactly that question. Popoff, who provides the Chandleresque narration, quickly admits, “I knew I was in over my head — I needed some help,” as if he were a down-in-the-mouth detective seeking one last chance for redemption. Yet the film holds together remarkably well and entertains us even as it strays down its peculiar cul-de-sac.

Strangely, there’s not a single Elvis song in Schmelvis. “The licensing fees were absolutely astronomical — tens of thousands of dollars,” Popoff explains. “There’s no way the Elvis estate would want to be associated with this film, not even in the title.”

Strangely, there’s not a single Elvis song in Schmelvis. “The licensing fees were absolutely astronomical — tens of thousands of dollars,” Popoff explains. “There’s no way the Elvis estate would want to be associated with this film, not even in the title.”

As it happens, the title derives from the stage name of a Montreal-area ultra-Orthodox-Jewish Elvis imitator, Dan Hartal, who performs at geriatric homes with born-again zeal; he says that if he ever met Elvis he’d like nothing better than “to put some tefillin on the guy.”

The producers invite Schmelvis to join them on a bizarre cinematic odyssey to the American South, where they intend to seek evidence of Presley’s Jewish roots as well as local reaction. Schmelvis, who claims a spiritual connection with Presley, quickly comes on board.

By a stroke of luck, the producers also get the brilliant idea of inviting prominent Montreal Rabbi Reuben Poupko, who readily puts his orthodox “hechshur” on the unorthodox adventure, and adds a welcome and witty commentary to it even as he questions its overall significance. “Does anyone care? Does it really mean anything?” he asks in the introductory scene in his office. “Wouldn’t the Gentile people down south react as if we were kidnapping their boy?”

Soon their Winnebago is rolling south to Elvis’s birthplace of Tupelo, Mississippi, to the strains of a schmaltzy borscht-belt song, “I’ve Got A Mammy But She Don’t Come From Alabamy.” First stop: a local cemetery, where, after a day-long search, the producers fail to locate the tombstone of Elvis’s supposedly Lithuanian-Jewish ancestor, who died about 1917. Jewish genealogists will find the setting and mission familiar: for many, the cemetery is a compulsory part of the modern Jewish quest for identity.

The next stop is Memphis, where they interview some of The King’s Jewish associates; this section nicely fleshes out the skeletal thesis and has a reassuring “documentary” feel to it.

They also attend what they call Elvis’s “23rd yahrzeit” outside the Graceland mansion, where they encounter scores of pilgrims, whose candles flicker like votive offerings in a church. Many who hear the report about their idol being Jewish only shrug: they’re used to hearing weird things about him. Others seem to welcome the news. “I don’t care if Elvis is Black, Buddhist, Jewish or Moslem,” says one woman. “Elvis is Elvis. Elvis is the King.”

As the filmmakers soon realize, the gathering itself is the real story. It’s clear that Elvis’s posthumous charisma seems laden with religious significance. “He’s a modern hero,” Rabbi Poupko deadpans as he walks amidst the crowd. “He comforts them when they’re lonely. He’s there with them. He lifts them up.”

The next day the film crew say kaddish over Elvis’s grave and the Rabbi completes the Christian analogy. “They took a man and made him into a God,” he observes. “Who’d they take? A good Jew. They did it again with Elvis. They took another child of our people and made a God out of him.”

The producers, who increasingly portray themselves as picaresque figures, suffer another setback when Schmelvis backs out of an appearance at a Memphis karaoke bar. Desperate for a scene that might “save the film,” they attempt to provoke the locals by suggesting that Elvis should be exhumed and reburied Jewishly. No one takes them seriously. They sink further into a morass of doubt, despair and navel-gazing, as they try to rescue their seemingly doomed project. Like true schlemiels, they make a comic virtue of being hard on their luck: that’s all they have left.

Did you know that Memphis has a “wailing wall” that is a popular site for Elvis fans? The producers are delighted to make this discovery, which points them in a new direction: Israel.

Granted, it’s quite a stretch between Graceland and the Holy Land, but, unbelievably, Israel boasts a popular Elvis tourist site, just outside Jerusalem, which the filmmakers do their best to capitalize on. They also plant a tree in Elvis’s memory and consult the Bible Codes to see if his name is embedded in the Torah. (It is, 61 times.)

On Jerusalem’s Ben Yehuda mall, Schmelvis demonstrates his prowess as a Jewish troubadour by singing to puzzled passers-by — not Love Me Tender, not You Ain’t Nothin’ But A Hound Dog, but rather Simmin Tov and Mazel Tov. None of this proves a thing, though, and their eccentric quest seems to get sillier by the moment.

Ultimately, the coterie of crazed Canadians returns to Memphis for one last try for the brass ring by way of an Elvis impersonator contest. Once again, nothing seems to go right for these hapless Jewish boys: Schmelvis, who is decked out in his usual yarmulka and glittering cape of Jewish stars, is pulled from the competition at the last moment because organizers suspect he’ll violate their “no religion and no politics” rule. Dejected, they wander next door into a Christian revival meeting — where worshippers pray for their souls in the name of Jesus. Closing credits roll over a wonderful live rendition of Amazing Grace.

On the surface, Schmelvis is a light-hearted comic expedition that turns strangely inward. Helen Zukerman, executive director of the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, calls it a “funny and quirky look at contemporary pop culture.”

While representatives of the Toronto festival expressed enthusiasm for Schmelvis from the start, Popoff reports that the film was rejected by the smaller Montreal and Vancouver Jewish film festivals.

“Looking at this project objectively, it’s probably one of the strangest Jewish films made in a long time,” he says. “It’s Bugs Bunny meets Duddy Kravitz. It’s certainly inspired lots of debate and questions, and I like that. A film that encourages debate is an effective film.”

Rabbi Poupko, who hasn’t yet seen the completed film, says it took him “about three seconds” to agree to participate in it. “When I first heard about it, I actually thought it might be a serious catalyst for some people with common issues of loss, identity and assimilation,” he says. “I thought people would see in Elvis’s life and his lost identity, much that has happened to American Jews. It’s a paradigm for a large swath of American Jews that has lost touch with their roots.”

Poupko says that he considered saying kaddish over Elvis’s grave as the best and most meaningful part of the project. “Halachically, he’s certainly Jewish,” he says, “and every Jewish soul deserves a kaddish.” ♦