Toronto, January 1928

Mourned by Thousands of Hebrews Whom He Helped and Encouraged — Instituted Labor Lyceum and Gave Freely to Charity

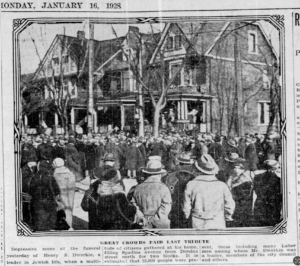

What manner of man was this, that mourners, estimated to number from ten to fifteen thousand, thronged about the place where the funeral service was held on a Sunday afternoon?

What had there been in his life and character to attract, to the funeral, an assemblage greater by many thousands than has paid tribute to departed citizens whose names and services to community and nation have made them known in every household?

Last Friday evening in crossing Queen street at John to buy a newspaper, Henry Dworkin was struck by a motor car. He died a few hours later. On Sunday a squad of twenty policemen was required to direct the crowds which sought to enter the Labor Lyceum, on Spadina avenue, to view the remains and participate in the funeral service. Four hundred motor cars formed the cortege to the cemetery.

“’Tis a piy that men like him lie under the earth.”

The speaker, a young Frenchman, an idealist, indicated a photograph of Henry Dworkin. And then came the enlightenment:

“Everyone who knew him went to Henry Dworkin when they needed to be helped — they never came away empty-handed or downhearted.”

In the picture one saw in the face of the man’s idealism also. It showed the friendly smile that played round the lips and irradiated the countenance.

BORN IN RUSSIA

“Twenty years ago there were not nearly as many Jews in Toronto as now — about five thousand then, probably,”remarked Abram Rhinewine, editor of the Hebrew Journal, a staunch friend and admirer of Dworkin and his family. Simply yet effectively, Mr. Rhinewine told the story of Henry and Edward Dworkin.

“The birthplace of the boys was the city of Ekaterinoslav, Southern Russia. Refugees from a Russian pogrom, the whole family migrated to Canada, but not all at the same time.”

Edward, elder brother, came first, in 1904. He was twenty-one years of age. Fleeing from the horrors of oppression behind him, what youthful ambitions and resolves fired his imagination he alone can tell. Obtaining a job in a paper box factory, the youth worked hard all day and did odd jobs at night to save enough to bring out his brother, living on bread and tea practically for one year.

Edward, elder brother, came first, in 1904. He was twenty-one years of age. Fleeing from the horrors of oppression behind him, what youthful ambitions and resolves fired his imagination he alone can tell. Obtaining a job in a paper box factory, the youth worked hard all day and did odd jobs at night to save enough to bring out his brother, living on bread and tea practically for one year.

Came a day in 1905 when he had funds to send for Henry.

Came another great day, in due course of time, when, trembling with eagerness, Edward waited in the old Union Station to greet his dearly beloved brother.

Henry, nineteen years old at that time, too was fired with ambition to aid the rest of the family to come. Together the boys worked in the factory, and at night opened a tiny store on Louisa street, where now stands the Registry Office.

“’Twas only a shack of a store, much like those one sees as one walks along parts of Queen street west today, but there were several rooms in it. They sold cigarettes, confectionery, soft drinks and Jewish newspapers, having obtained an agency from a firm in New York.

Though there were a few synagogues in Toronto then, the Hebrew population was not organized. Immigrants found no one place or institution where they could go — until they heard of Dworkin’s store. It became a meeting place — a haven for weary wanderers.

The brothers after a year and a half sent for their sister, who tended store for them in the evenings. Their father is still living.

Gradually it came about that Edward devoted himself to the business end of the factory and Henry to the store.

Gradually it came about that Edward devoted himself to the business end of the factory and Henry to the store.

My money and time is yours to help whom you will,” said Edward, with complete confidence in his brother.

And so, like a beacon light whose beams reached across the sea, it became known to Jewish immigrants where a friendly face could be found and a helping hand when they reached these shores.

My own experience was this,” said Mr. Rhinewine. “A group of three, we came to Toronto, my wife, a man friend and myself. I had only the address of a friend here to whom I could go on arrival.

“I found when I came that my friend had left for the States six weeks before we landed.

“We heard of Dworkin’s store and went there. I remember his friendly smile and manner as he welcomed us. I told him I was trying to find a room, but could not at once get one furnished.

“His answer was, ‘Take mine.’ Without apparently a thought as to our honesty, he placed his room at my disposal, moving into another one somewhere in the store. He bade us stay as long as we needed accommodation.

“As I recall now that there were always thirty or forty people in his store, sitting around a stove. Those who had no work came there and got in touch with others who could put them in the way of jobs.

“During 1907 and 1909 there was a financial crisis and much unemployment. The Dworkins weren’t making much money then, and Henry could only afford — sometimes — to buy six or seven loaves of bread, but this he did. I can see him cutting it up and handing it to those waiting there.

“If you wanted tobacco and had no money you could have credit. If you could, you paid; if you hadn’t the money, well, you didn’t – that was the way of it. Newspapers, too, were provided. You bought them if you could; if you had no money, they were there anyway.

“The brothers in due time sent for their parents. The father opened a repair bicycle shop in the back of the store and did well. They moved to 64 Elizabeth street and operated on a little larger scale.

“At the same time Henry and his brother opened a restaurant, subletting the old Minto House, corner of Bay and Louisa streets. They kept it going about a year, but lost nearly all their investment. You see, everyone was given food whether they paid or not.

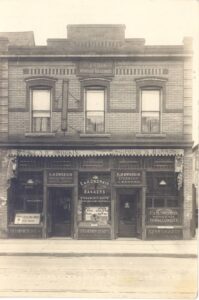

“Afterwards they devoted themselves to their business, and, Elizabeth street becoming known as Chinatown, they removed to 525 Dundas street west, their present site, and opened two departments – one tobacco, the other steamship agencies.

“Afterwards they devoted themselves to their business, and, Elizabeth street becoming known as Chinatown, they removed to 525 Dundas street west, their present site, and opened two departments – one tobacco, the other steamship agencies.

“Both brothers had married by this time, and their wives pluckily played their parts, and still do, in the business.

“Henry Dworkin became anxious for Jewish people to have their own labor institution — it became an ambition — and it was through his efforts they have their Labor Lyceum now. He gave liberally to projects, Jewish and non-Jewish. His philosophy was:

“Since the project is launched and people are contributing, it is worthy of support.”

“It was on the night he was killed – Friday January 13th that he was to have been chairman at a board of directors meeting at the Labor Lyceum. The meeting was due to begin at 8.30. At his non-appearance they kept phoning until 10 p.m., but could get no reply from his home, so the meeting was postponed.

“It was on the night he was killed – Friday January 13th that he was to have been chairman at a board of directors meeting at the Labor Lyceum. The meeting was due to begin at 8.30. At his non-appearance they kept phoning until 10 p.m., but could get no reply from his home, so the meeting was postponed.

“The love of the brothers that even death has not severed was demonstrated when at the grave Edward vowed to take his brother’s place in continuing his good work.”

Other friends spoken to regarding the life of Henry Dworkin stressed the liberality of the man.

“He gave away more than he was worth when he died,’ was all the family would say when asked if it were possible to compute in dollars and cents as well as in kindness what he had done for the city. From all appearances he had been a successful business man at the time of his death.

An exciting incident in his life was a trip back to Poland made a few years ago. His brother explained:

“During the war remittances sent to bring people to Canada were frequently delayed. Advices piled up in Poland and then the money market changed. Money sent for a purpose at one date was not sufficient later. Trouble ensued, and Henry journeyed over as soon as possible to straighten matters out. His wife followed him.

“There he was not known so well. People said, ‘I gave all my money to him.’ He was arrested. Henry at once paid the difference in increased rates, and people promised to pay him back. Some did, but many forgot, and the matter ended – his loss.”

Others say that Henry Dworkin was exceptionally broad minded, and it would seem so from messages, letters and telegrams of sympathy received from all over the country by his widow, from all classes and faiths.

An unusual departure from Hebrew custom at his funeral was that instead of the customary shroud Henry Dworkin was buried wearing a frock coat, etc.

“Death is the great leveller. There should not be many flowers and for and not another – rich and poor at this time rank the same. Therefore flowers are not allowed, and the conventional shroud is the garb for all classes of society,” is the explanation of the Jewish custom. ♦

* * *

MEMORIAL PLANNED FOR HENRY DWORKIN

To show their esteem for the late Henry Dworkin, Jewish leader, the Ladies’ Auxiliary of Mount Sinai Hospital, of which Mrs. Dworkin is president, are presenting her with a painting of her husband. N. Soboloff is the artist commissioned to do the portrait.

Further indications of esteem are shown by the setting apart of one of the rooms in the Labor Lyceum to establish a Jewish library in his name.

In memory of him, the family will present to all synagogues in the city Hebrew prayer books, will establish a scholarship, and will furnish a room in the Mount Sinai Hospital in the name of Henry Dworkin.

On the 29th of January, a mass memorial meeting in honor of the late Henry Dworkin will be held under the auspices of 25 organizations, in the Standard Theatre, Dundas and Spadina, at 2 p.m. It is planned to have the various speakers transferred to different halls to accommodate all who may wish to attend. ♦

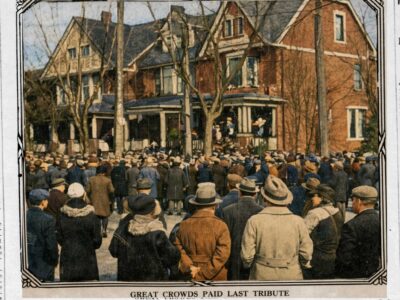

Photo caption (top): A large multitude of citizens gathered at his home, filling Spadina avenue from Dundas street north for two blocks. It is estimated that 15,000 people were present, these including many Labor men among whom Mr. Dworkin was a leader, members of the city council and others.

Near top, at right: Dworkin (tall man at centre) with a group of immigrants from Kielce, recent arrivals to Toronto, ca 1920 (colourized).

Dworkin store on Dundas St W (OJA)

Labor Lyceum, Spadina at St. Andrews (Speisman Collection)

Below: original newspaper photo, colourized above.