From The London Jewish Chronicle, August 11, 1916

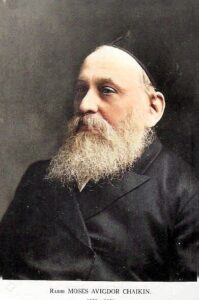

◊ BG Intro: Rabbi Moses Avigdor Chaikin (1852–1928) was a distinguished rabbinic scholar, teacher, and communal leader whose life reflected the intellectual vitality and migratory experience of Eastern European Jewry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born in Shklow, in the Russian Empire, and raised within a Chabad-Lubavitch milieu, he received rabbinic ordination from some of the era’s most renowned authorities. His career took him across multiple European centers—Paris, Rostov-on-Don, Sheffield—before he settled in London in 1901.

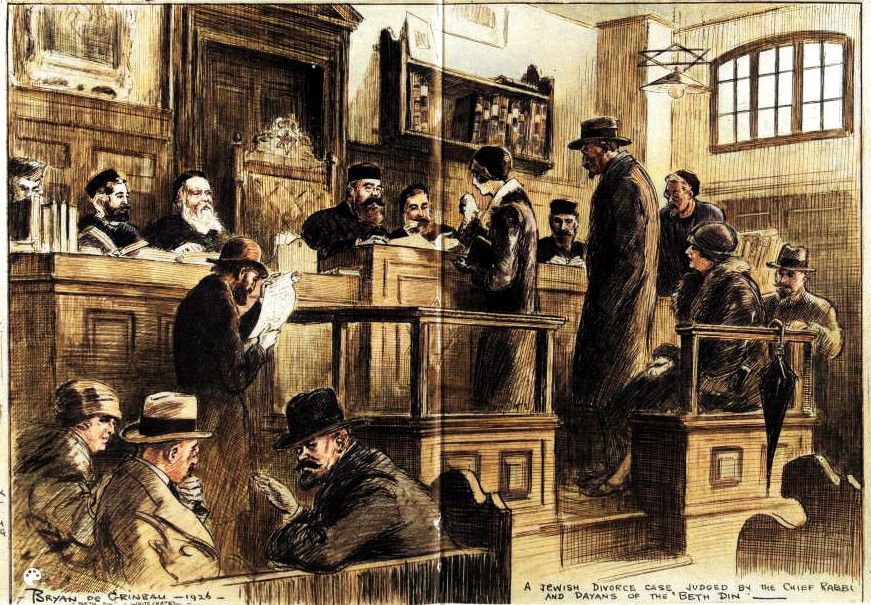

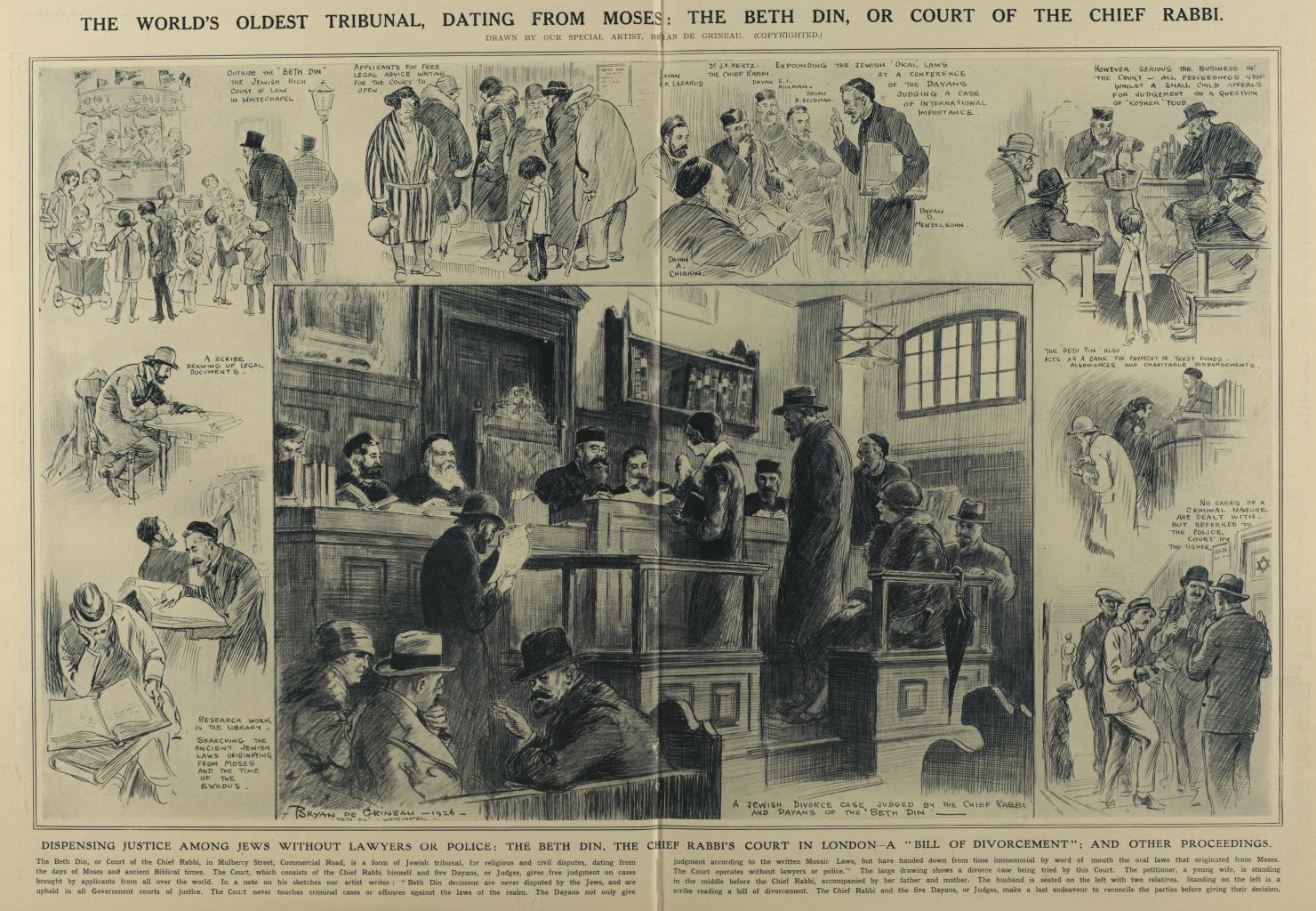

There he became the senior rabbi of the Federation of Synagogues and, in 1911, a dayan of the London Beth Din, making him a central figure in the religious life of immigrant Jews in the East End.

Fluent in several languages and steeped in classical Jewish learning, Chaikin was an accomplished author whose works made Jewish history and learning accessible to a broad audience. He guided the immigrant Jews of London’s East End through practical halakhic, social, and wartime challenges. His work was intimate, pastoral, and grounded in the classical study hall.

Fluent in several languages and steeped in classical Jewish learning, Chaikin was an accomplished author whose works made Jewish history and learning accessible to a broad audience. He guided the immigrant Jews of London’s East End through practical halakhic, social, and wartime challenges. His work was intimate, pastoral, and grounded in the classical study hall.

In 1926 he retired to the Land of Israel, where he died two years later.

The following interview explores the state of Jewish life, learning, and spirit in the East European ghettos during World War I.

The Spirit of the Ghetto

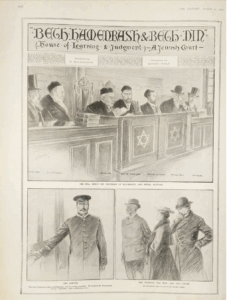

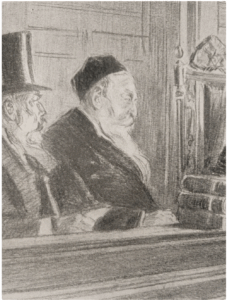

◊ JC Intro: Away in the East End, the counterpart of the Ghetto of Central Europe, a spirit of optimism is still found dominant, notwithstanding the terrible times in which we are living. Hoary-bearded rabbis with long flowing beards, sit rocking themselves, preferably in some Beth Hamedrash, over a folio of Mishnays, unruffled by the catastrophic march of daily sensations. For such, the ardent love of the Torah far transcends the mundane round of a material world.

Our representative recently had an ample opportunity of witnessing a manifestation of this spirit of the Ghetto at the house of Dayan Chaikin on Saturday evening, soon after the Havdalah ceremony. The venerable Dayan had hardly finished the home service, making his “distinction between things holy and things profane,” when a stream of humble visitors poured in soliciting his advice and help on matters in connection with the war; such as sending money to starving relatives in Russia, the means of ascertaining their whereabouts, about lost relatives, naturalization, and how to enlist their sons for military service in the army.

In the intervals of these brief catechisms our representative was able to procure an interview for the Jewish Chronicle, and here are some of the replies that the kindly Dayan Chaikin supplied. ◊

AN EMANCIPATED JEWRY.

What are your views as to the effects of the war on the Jewry of Central Europe?

What are your views as to the effects of the war on the Jewry of Central Europe?

“The end of the war is not yet in sight, so it is really very difficult to formulate any opinions in this respect. It may lead to the complete emancipation of the Jews in the Central Empires. This may be due to their being rewarded for loyalty as a part of an emancipated whole. The peoples of the Central Empires are not yet endowed with full rights, as the citizens of the great liberal states of Western Europe. The various subject races of the Central Empires still groan beneath the yoke, nor have the democratic forces in the enemy countries yet reached to that stage that they could influence their several governments for good . . . .

“The various governments may come to realize that the Jews liberated would form a valuable asset to the body politic. But, it seems to me, however, that there will be a great revival of Hebrew learning together with a strong nationalistic spirit. The lamps of learning which have been lit in the Ghetto neither this war nor any other war will ever extinguish.

THE CORD OF LOVE.

“History which repeats itself will repeat itself again in the case of the yeshivahs and beth hamedrashim in Central Europe. The memory of Rabbi Jochanan ben Zakkai, the founder of the Yeshivah of Yavne, is deeply engraved in our heart. We fasten our love upon him, and, like an elastic cord, that love broke not, but only drew with more force as the distance became great. The beings we love do not die . . . .

THE EVOLUTION OF GHETTO LEARNING.

“Thus it was that Rabbi Jochanan petitioned for permission to keep open his school at Yavne, feeling convinced that the power of the schools would eventually prove a great factor for preserving Jewry.

“From the beginning of the reign of Yazdejerd II. of Persia in 442 until far into the reign of Cobad (491–531), hostility to the Jews was the rule: it culminated under Firuz (461–488) in the incarceration and execution of men in eminent positions, followed in 479 by a royal decree to shut all the schools and to enforce the adoption of Persian laws. As a matter of course, the schools were re-opened after a short reign of terror, and the laws of the Medes and the Persians were never supreme.

“Divine Providence through an accidental circumstance ordained that a short time before Babylon’s part in Jewish history was played out, a branch of learning from the East should be transplanted to Spain and France, where it soon took root, and flourished so luxuriantly as to overshadow the fame of its parent stock.

TALMUDIC JUDAISM IN RUSSIA AND POLAND.

“In 787 Charlemagne transplanted Rabbi Kalonymus with his own sons, Rabbi Moses and a nephew to Mainz, where they opened schools, which continued to flourish under the care of their successors, and the Jews of Northern France were thus greatly influenced by this change.

“At the end of the 12th century, as a result of the Crusades, the Jews emigrated to Poland. Then an early Jewish immigration wended its way into the old Russian principality of Kiev, partly from the Crimea and partly from Byzantium . . . . And so it was that Talmudic Judaism found its most faithful reproduction in Poland and Russia; the school and the synagogue were now to be Jewry’s impregnable citadel, and the law its palladium.

“The testimony that the Torah we love does not die, might be perennially witnessed at the doors of the Talmud Torahs, notably at the time of the admission of new pupils. It burns and shines in the eyes of the young children, and will never be extinguished.”

ISRAEL VERSUS THE WORLD.

So you are optimistic of the future of Judaism?

“Quite! The eternal mystery and miracle of the ages has been the persistence of Israel. While the mighty empires of Assyria, Babylonia, Rome and Greece rose to fame, spreading their conquests over large and immense portions of the earth’s surface, and extending their subject-inhabitants by millions, what is left of them to-day is but the shadow of a name. All that they had wrought for, and all that they had fought for has crumbled upon the ruins of their disorganization. Israel alone has withstood the tempests of time. His inner faith in the all-good and his moral fibre, his loyalty to the Torah and the teachings of the Rabbis — his adamantine spirit is what has stood him in stead like a rock in the sea.

THE HEBREW REVIVAL IN FUGITIVE COMMUNITIES.

Still, has not the present upheaval exploded the work of centuries of Jewish learning in Russia and Poland?

“No, the work has only been scattered. As I have shown you in the historical parallels, that though this learning and piety may be uprooted, it will on transplantation flourish elsewhere. Take for example Moscow, which has already opened a Hebrew children’s home for 150 refugee children and you have another reply to your query. Similarly, Hebrew homes for fugitive children have been opened in Saratov and Nizhny Novgorod; chedarim in Bogorodsk and Yelets: libraries in Saratov, Petrograd and Moscow have started special information bureaux for Hebrew teachers.

“It is true that the war has suffered, but this is merely a temporary set-back. It will come right in the end. Taking one case out of many others like it, in Ciecowicze [sic], in the province of Grodno, there were 8,000 inhabitants before the outbreak of the war. During the siege they were compelled to leave the town, and do so they left themselves to the wood round about the town.”

“After the battle some of the Jews, only 3,000 of them, returned, but they found the place in ruins. Five hundred houses with all the schools and synagogues were demolished. The poor inhabitants then betook themselves to the cellars of the houses, which had not been destroyed by fire, and they hastily constructed booths for those less fortunate than themselves who were shelterless. Gradually the work of reconstruction began, hebrew schools and chedarim were opened, synagogues established, beth hamedrashim inaugurated, and the whole sphere of Jewish communal life set in motion again. So it will be with Jewry in general after the war.”

THE LEADERLESS GHETTOS.

What light does all this throw on the future of the ghetto?

“To say that the ghetto is a united whole would be an exaggeration of the truth, for in the ghetto there are many other little ghettos, each striving after its own welfare and serving their own interests. There is no universal ghetto as such, recognizing one leader or head, but each working out its salvation in its own individual way.

“The present communal life of the scattered Jewish communities consists of many incoherent parts. It needs a connecting force to draw them together, and this is bound to come one day as soon as Jewry learns the significance and object of its mission on earth.

“The present communal life of the scattered Jewish communities consists of many incoherent parts. It needs a connecting force to draw them together, and this is bound to come one day as soon as Jewry learns the significance and object of its mission on earth.

“For it must be remembered that the ghetto is supremely idealistic, rearing a race of dreamers, scholars, visionaries, teachers, thinkers, and poets. It breathes humility and simplicity. It brings man nearer to his Maker. The type of life that teaches by its sweet peacefulness and earnest unostentatious conduct is the work of life of the ghetto. The ghetto is rich in these qualities, and who can single out one above the other?

THE MESSAGE.

Then what is your message?

“My message to Jewry is that they be witnesses of the living God, such indeed is their mission: for their language, literature, customs, traditions, and character—these, too, have all survived. It is one of the many miracles of Jewish history. ‘Then, indeed, in the blissful time,’ will the Torah go forth from Zion and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.” [Is. 2:3, Mic. 4:2] ♦