Sometimes when author Daniel Mendelsohn was a boy, elderly relatives would cry at the sight of him, so great was his resemblance to his great-uncle Shmiel Jaeger. From some handwriting on the back of a photograph, Mendelsohn knew that Shmiel and his wife Ester and their daughters Lorka, Frydka, Ruchele and Bronia had been “killed by the Nazis,” but his beloved grandfather always skipped quickly over their photographs in his photo album without a word.

Sometimes when author Daniel Mendelsohn was a boy, elderly relatives would cry at the sight of him, so great was his resemblance to his great-uncle Shmiel Jaeger. From some handwriting on the back of a photograph, Mendelsohn knew that Shmiel and his wife Ester and their daughters Lorka, Frydka, Ruchele and Bronia had been “killed by the Nazis,” but his beloved grandfather always skipped quickly over their photographs in his photo album without a word.

Consequently, his ears became highly attuned to “scraps of whispers, fragments of conversations that I knew I wasn’t supposed to hear.” He had heard so much about all other aspects of his American Jewish family — but who were these missing relatives?

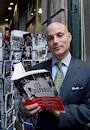

“My grandfather told me all these stories, all these things, but he never talked about his brother and sister-in-law and the four girls who, to me, seemed not so much dead as lost, vanished not only from the world but — even more terrible to me — from my grandfather’s stories,” Mendelsohn writes in his book The Lost: a search for six of six million (HarperCollins, 2006).

“Which is why, out of all this history, all these people, the ones I knew the least about were the six who were murdered, who had, it seemed to me then, the most stunning story of all, the one most worthy to be told. But on this subject, my loquacious grandpa remained silent, and his silence, unusual and tense, irradiated the subject of Shmiel and his family, making them unmentionable and, therefore, unknowable.”

Like an astronomical black hole in a distant galaxy, Mendelsohn’s silent, invisible quarry — his great-uncle Shmiel and family — exerts an emotional gravity that ultimately overpowers him. This riveting narrative, part memoir and part meditation, is the result of his ruminative quest for knowledge and truth.

Upon discovering after his grandfather’s death a cache of desperate letters sent by Shmiel to his grandfather in 1939, Mendelsohn embarks in search of eyewitnesses and evidence testifying to the specific fate of his perished kin. While his genealogical odyssey takes him to Australia, Israel, Sweden, Denmark and other places, his first destination is Bolechow, the family’s ancestral shtetl, where Shmiel had been a butcher.

It is in Bolechow that he first experiences those enthralling “vertiginous feelings” upon meeting strangers who speak knowingly of his lost relatives: “All that distance, all those years; and then there she was, right there across the table, there he was, chatting with me on the phone, there they were, still out there if you knew where to find them: remembering them.” An impossible, gaping abyss is momentarily bridged as the seeker, wrestling with dark angels, recovers precious facts and histories from mute, unknowing eternity.

Family tree historians who utilize JewishGen and other genealogical websites will feel an instant familiarity with Mendelsohn’s frequent descriptions of these amazing resources, details of which he weaves into the fabric of his literary narrative. Jonathan Safran Foer may have mentioned some of them in his award-winning satirical novel Everything Is Illuminated, it was for an entirely different purpose. While Safran Foer excelled at cutting up American Jews who revisit the shtetl, Mendelsohn’s somber quest is infused with the unwritten commandment that has possessed many a Holocaust researcher: Thou Shalt Not Give Hitler A Posthumous Victory.

Although Mendelsohn engages in genealogical research, his purpose is not to produce an ordinary family history but rather a more noble sort of bibliographic matzevah or monument to posterity. With The Lost, Mendelsohn erects a literary monument in memory of his vanished relatives that may ultimately be one of the most enduring in our psychic cemetery.

The Lost is essentially a Proustian-type exercise in which the author weaves many personal associations from earliest childhood forward into the narrative, as though intent on recapturing the sights, smells, sounds, sensations of a lost time.

Mendelsohn also indulges in exegetical discussion of the early chapters of B’reishit, particularly those dealing with Cain and Abel, and Noach. He’s particularly drawn to the motif of brother killing brother, reflected not only in the historical backdrop of the Holocaust but also in the inferred friction between Shmiel and Mendelsohn’s grandfather, who did not answer his pleading letters and may have been forever frozen by guilt.

The author, a classical scholar, further enriches the text with allusions from ancient Greek and Latin sources. Noting the power of certain objects to evoke deep emotion, he offers a quote from Virgil: Sunt lacrimae rerum, which translates as “There are tears in things.”

The subject being so close to his heart, the author treads fertile ground and constructs many meaningful puns and turns of phrase. In describing Auschwitz, for example, he trades his usual sincere yearning for some of Safran Foer’s biting satire. Regarding the death camp’s Arbeit Macht Frei gates and other features, he observes: “All of this has been reproduced, photographed, filmed, broadcast, and published so often that by the time you go there, you find yourself looking for what it is difficult not to think of as the ‘attractions,’ for the displays of the artificial limbs or glasses or hair, more or less as you’d look for the newly reconstructed Apatosaurus at the Natural History Museum.”

In The Lost, Mendelsohn gives expression to a sensibility that seems to infuse much of Diasporan Jewry today. My one wish is that he could have done so in a book of 250 rather than 512 pages. Although the subject is vast (every person is a world, after all) our precious time is finite. Alas, this excellent, moving book is weighted with a length that eventually becomes trying and ultimately dullening. The editors should have insisted on an abridgement. ♦

© 2006 by Bill Gladstone