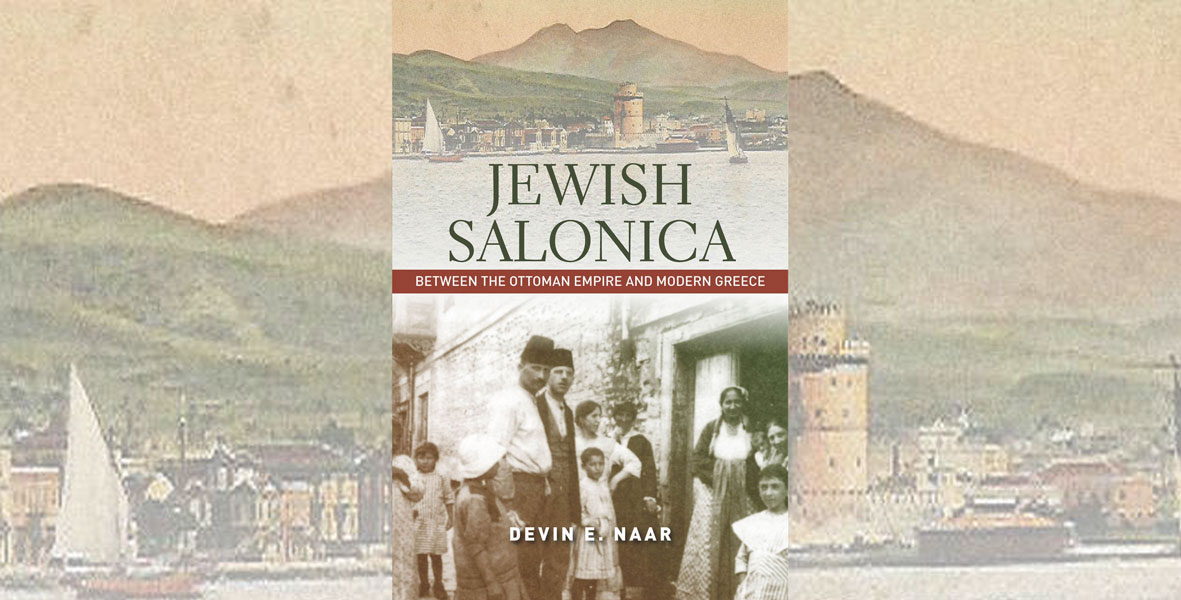

Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece

By Devin E. Naar. Stanford University Press 2016.

by Bill Gladstone

Jews first arrived in the city of Salonica, formerly known as Thessaloniki, soon after their dispersal following the Roman conquest of ancient Israel. Salonica again became a prime destination for Sephardic Jews after Spain expelled the Jews in 1492. From then until the Second World War, Jews were close to a majority of the population.

A part of the former Ottoman Empire, Salonica was a strategic Aegean port and a thriving multicultural metropolis at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East. It was a place in which the Jews attained significant cultural, commercial, political and familial links across a wide geographical range from Sarajevo to Sofia, Istanbul to Cairo.

A part of the former Ottoman Empire, Salonica was a strategic Aegean port and a thriving multicultural metropolis at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East. It was a place in which the Jews attained significant cultural, commercial, political and familial links across a wide geographical range from Sarajevo to Sofia, Istanbul to Cairo.

With a self-assured Jewish community that at its height exceeded 60,000 — even up to 100,000 by some estimates — Salonica attained a legacy as “the Jerusalem of the Balkans” and was home to the largest Sephardic community in the world. The community possessed a historic sense of heritage, grandeur and belonging. By the early 20th century, Salonica had become such a dynamic Jewish center that the Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky, upon visiting in 1909, declared it “the most Jewish city in the world.”

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, there was short-lived talk of making Salonica into an independent Jewish principality. However, Greece annexed the city in 1913 and a calamitous fire swept through it in 1917. These events marked the beginning of a significant exodus of Jews to New York, Tel Aviv and other destinations.

As Devin E. Naar writes in this historical narrative, the Germans occupied Salonica during World War Two but it was the Greeks who, at a peak of nationalistic fervour, destroyed the ancient Jewish cemetery, which had been one of the largest in the world. The massive destruction and looting of the cemetery was “a precursor to the imminent total destruction of the whole Jewish community of Salonica, the most populous center of Judaism in the East,” Naar observes. Tragically, the Germans deported most of the Jews to Auschwitz.

Since Naar’s family came from Salonica, he had heard about that city since childhood. His great-grandfather was a bearded rabbi who appeared in a photograph wearing an Ottoman fez. Among the family members who stayed behind and perished was an uncle who worked in a Jewish soup kitchen and distributed food to the sick and elderly until the Nazis boarded them all onto trains to Auschwitz.

In compiling this scholarly study, for which he seemingly left no stone unturned, Naar visited archives and museums in Salonica, Athens, Jerusalem, Moscow, New York and Washington DC. His sources, which are listed in the copious notes, include the extant archives of the Jewish community in the period 1917 to 1941, mostly written in Judeo-Spanish but also in Greek, Hebrew and French.

Speaking of stones, the Salonica Jewish cemetery stretched across 86 acres and held an estimated 350,000 densely-packed graves; according to Naar, it was the largest Jewish burial ground in all of Europe. The next largest, in Warsaw, contains 150,000 graves over some 74 acres. Naar devotes considerable space to the efforts of teacher-historian Michael Molho, who transcribed many historic stones even as 500 municipal workers were destroying the cemetery with pickaxes. Today the sprawling campus of the Aristotle University of Salonica occupies the site.

The stones easily reveal that Salonica boasted a diverse and multicultural Jewish community. While most of the tombstone inscriptions were in Hebrew, Judeo-Spanish began appearing in the 1700s, along with Portuguese on the gravestones of former conversos who were buried as Jews; Italian on the graves of merchant families from Livorno; as well as French, Yiddish, Ottoman Turkish and Greek.

Wearing a proud cloak as “Hellenistic” Jews, the Salonican Hebrews felt sure of themselves as Greeks. But when the protective multicultural fabric unfurled due to heightened nationalistic tensions, the Jews were displaced and destroyed. Ironically, many Salonican Jews strengthened their spirits by singing Greek nationalistic songs in the death camp.

Jewish Salonica tells an important chapter of Jewish history. Too bad that, like so many others, it ends in tragedy. ♦