The extraordinary story of Eli Hyman first came to my attention with the following notice that appeared in the Toronto Daily Star of December 20, 1902:

* * *

WILL BE BURIED SUNDAY

Rabbi Jacobs Will Conduct the Funeral from Holy Blossom Synagogue

The funeral of the late Eli Hyman, the Jewish miser who died in the General Hospital, will take place Sunday afternoon from the Church of the Holy Blossom Synagogue. Rabbi Jacobs will conduct the ceremony, which is expected to be an imposing one.

A formal inquest was opened this afternoon by Coroner Johnson for the purpose of identifying the remains. This was necessary since Hyman was admitted to the hospital under the name of Henry Saloski. ♦

* * *

Why in the world did the Toronto Star find it necessary to reduce this man to a negative cultural stereotype? At first, I imagined the newspaper was simply relying upon a common trope of the tight-fisted miserly Jew, long familiar to most readers and propagated for centuries by stage plays such as Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. But a little more “digging” turned up several more news stories, some of which were reprinted in newspapers as far away as New Zealand.

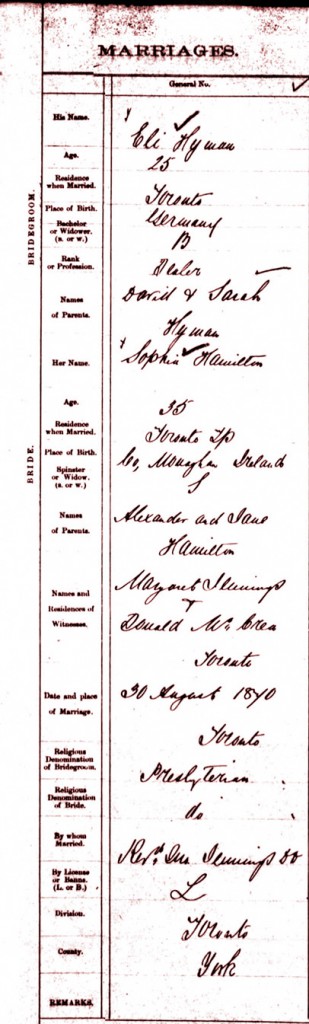

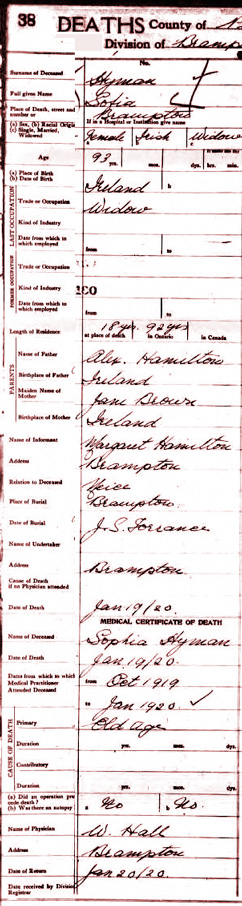

Some genealogical research has added a few more details. Eli Hyman was born in Germany about 1846 and was among the first handful of Jews in southern Ontario; he married an Irish-Presbyterian, Sophie Hamilton, in Toronto in 1870. In 1881 he and his wife were living in Brampton; the census of that year described him as a “boot agent.” In 1891, the couple were living in Brampton, but now he was a “farm labourer.” The 1901 census indicates he came to Canada about 1850.

Here, then is the full story of Eli Hyman — husband, father, and evidently, savvy businessman — who, sadly, achieved his greatest renown as the “Jewish miser” of Toronto.

* * *

Death Reveals Miser’s Wealth

Eli Hyman Imposed on Charity for Twenty-five Years.

DIED AT THE HOSPITAL.

Worth Over One Hundred Thousand Dollars.

Gathered Rags and Sold Newspapers — Pockets Were Stuffed with Scrip — Begged For A Car Ticket to Go to the Hospital.

From the Toronto Globe, December 18, 1902

The death of an aged Jewish rag-picker at the General Hospital at 1 o’clock yesterday afternoon brought to light one of the most remarkable cases of avarice that has ever been recorded. That a wealthy old man could for over 25 years play the part of a destitute old pauper without detection seems incredible. The death of Eli Hyman, however, revealed the fact that he was worth at least $100,000 and possibly much more.

The death of an aged Jewish rag-picker at the General Hospital at 1 o’clock yesterday afternoon brought to light one of the most remarkable cases of avarice that has ever been recorded. That a wealthy old man could for over 25 years play the part of a destitute old pauper without detection seems incredible. The death of Eli Hyman, however, revealed the fact that he was worth at least $100,000 and possibly much more.

Under the name of Henry Zolinski, he went to the hospital on Saturday evening last, a picture of filth, misery and disease. He had begged a car ticket, he said, to come to the hospital. His very appearance was repugnant and he was so dirty that the ward tenders, accustomed as they are to such things, shrank in disgust from his presence. He had a city order and was put to bed after being washed. It was seen that he was suffering from pneumonia and pleurisy combined, and that the diseases had already obtained a strong hold. He was placed in ward six, a public ward, and given every care.

Bonds in a Dirty Handkerchief.

When Hyman entered the hospital he said that he was a “very poor man” and had “no money, relations or friends.” The name of Rabbi S. Jacobs of 577 Church Street was given as his only acquaintance, and that gentleman was notified and visited the sick man until the hour of his death. During his illness Hyman was most impatient and exacting and demanded ceaseless attention. When put to bed he handed to the nurse a dirty red handkerchief loosely tied in a knot and she put it in a table drawer near the bed.

When Hyman entered the hospital he said that he was a “very poor man” and had “no money, relations or friends.” The name of Rabbi S. Jacobs of 577 Church Street was given as his only acquaintance, and that gentleman was notified and visited the sick man until the hour of his death. During his illness Hyman was most impatient and exacting and demanded ceaseless attention. When put to bed he handed to the nurse a dirty red handkerchief loosely tied in a knot and she put it in a table drawer near the bed.

No one suspected that Zolinski was any other than a destitute old rag-picker until his death came. then his effects were examined and the astounding facts were revealed. The dirty red handkerchief contained a formidable roll of bonds and scrip amounting in value to $31,000. Of this $17,000 was in one company and $14,000 in another. His pockets, moreover, were stuffed with similar securities, and the total value of those found in his effects at the hospital was over $50,000. The ruling passion of the old miser remained with him to the end, and with his dying breath he gasped, “My vest, my vest.” Before this he had said that he wanted to say something to the Rabbi, but put it off on account of his weakness.

A Beggar for Years.

Eli Hyman is known to have been the old man’s correct name. “Henry Zolinski” and “Davis” were pseudonyms which he used at different times. He was 70 years of age, was born in Russia, and had been in Toronto for 32 years. Begging seems to have been a mania with him, for, although among some of the Jews of the city his fraudulent life was discovered last spring, he continued his old manner of living.

In the mornings he appeared as a rag, bone and bottle collector and begged from door to door. He was well known in the eastern parts of the city around Jarvis, Carlton, Parliament and Queen streets. He would ask most frequently for a car ticket, saying that he had been in the hospital and wanted to get down to York street. In the evenings he was in the habit of selling newspapers, and complained that the newsboys interfered and tried to stop him. When night came he would be seen trying to sell his “last paper.” He always had this last one tucked away beneath his coat, as though it were precious, and his appeal for frequently successful. When The Sunday World and the New York papers came he would sell them “two for five,” and tell the purchaser that he was losing money on it. This often resulted in a kind-hearted man giving him ten cents instead of five cents. He had no home in the city, but slept in alleys and outhouses.

Many other stories could be told of his schemes. Whenever he purchased stock in a company he went to the office and told them that he would call for the dividends, and they need not send them to him. When he called he would always demand the stamp which the company had saved by not mailing the dividend.

His Wife.

Hyman was a married man. Mrs. Sophia Hyman, his wife, lives in Churchville, a village near Streetsville, and is currently reported to be well off. They were married in 1870 by the late Dr. Jennings. She was notified yesterday of her husband’s death, and came to the . . . (few lines missing) . . . received charity from the Hebrew Benevolent Society. Last spring, however, some stock brokers made it known that the old man was well off, and a secret investigation was made, by which the extent of his wealth was learned, and he was no longer able to impose upon the charitable men of his own race. He, however, joined the pensioners’ staff of the Holy Blossom Synagogue, and obtained some small pay for assisting in the conduct of the morning and evening services. Rabbi Jacobs considered him to be well versed in the Jewish law and liturgy.

Some of his Investments.

Among the companies in which he had stock, according to the scrip found among his effects, are the following: — Canada Permanent, Canada Landed, British America Assurance, British Canadian Loan, Western Assurance, Toronto Electric Light, Dominion Savings & Investment, Union Loan & Savings, Building & Loan Association, London & Canadian Loan & Agency, Dominion Telegraph, Land Security Companies, and the Canada Cycle & Motor Co.

When the effects were examined at the hospital it was seen that he had taken the minutest care about each piece of scrip. Every certificate was folded and pressed and put inside an envelope, addressed to Sophie Hyman, Churchville, Ontario. Each envelope had been carefully pressed, and when put together the bundle had been pressed in a letter press or in some other way, so that it would occupy as little space as possible, and could easily be carried in a pocket. The bundle was placed in an oilcloth cover to keep out the moisture, and this was again pressed, and the whole tied up in the red handkerchief. Mrs. Hyman will apply for administration of the estate, and Mr. S. King will take charge of the matter.

A post-mortem examination will be held upon his remains by Dr. Norman Anderson this morning. Coroner Johnson has issued a warrant for an inquest into the cause of death, to be held on Friday. ♦

* * *

The story evidently had “legs” and travelled far — even to remote New Zealand, where an account appeared in The Wanganui Herald of February 20, 1903, under the heading, “MISER’S END: Remarkable Avarice.” Unfortunately, the focus was on the late Mr. Hyman’s extreme “avarice” and none whatsoever on our modern perception that he was clearly suffering from mental illness. Excerpts:

* * *

A remarkable and, so far as Canada is concerned, unprecedented case of avarice was brought to light in Toronto, Canada, recently. Eli Hyman, a Jew, who had lived in that city for 32 years, was admitted to the hospital as a non-paying patient. A local doctor found him suffering from a very heavy cold, and gave an order for his admission at the city’s expense. He begged a street car ticket to take him to the hospital, and the regular ward attendants found him in such a state of filth that they shrank from him in disgust. He was given a bath and put to bed, when the house surgeon found that he was suffering from pneumonia. He seemed anxious to impress upon the hospital authorities the fact that he was destitute, and therefore could not pay anything for medical treatment . . . .

A remarkable and, so far as Canada is concerned, unprecedented case of avarice was brought to light in Toronto, Canada, recently. Eli Hyman, a Jew, who had lived in that city for 32 years, was admitted to the hospital as a non-paying patient. A local doctor found him suffering from a very heavy cold, and gave an order for his admission at the city’s expense. He begged a street car ticket to take him to the hospital, and the regular ward attendants found him in such a state of filth that they shrank from him in disgust. He was given a bath and put to bed, when the house surgeon found that he was suffering from pneumonia. He seemed anxious to impress upon the hospital authorities the fact that he was destitute, and therefore could not pay anything for medical treatment . . . .

Four days later he died, and when the parcel in the handkerchief was opened it was found to contain £8000 in first-class securities and a considerable sum of money. Inside the lining of the vest other bonds were discovered, which brought the total up to over £20,000. This was not only a great surprise to the nurse, but to the people of Toronto, when the fact was published, for Hyman was a well-known character in the city. He was always regarded as an unfortunate beggar, barely able to keep body and soul together. As a mendicant, however, he was an artist.

For years the old man had slept in a shed on York Street. He spent his forenoon in gathering rags and junk, and in the afternoon he would sell newspapers on the street. He always had a last paper to sell, and his stimulated distress frequently led to some generous pedestrian giving him a small donation in silver. So successfully did he impose on everyone that even his Jewish friends were deceived, and for years he had been allowed a small pension out of the charity fund contributed by the Hebrew community of Toronto. In fact, while he was not sleeping he spent his time in either begging or making small sums by the selling of rags and newspapers. He denied himself every trace of bodily comfort, and one of the mysteries connected with his case is the means by which he managed to purchase valuable securities without the fact being known.

After Hyman’s death it transpired that he had a wife living some 40 miles from Toronto, who he occasionally visited. She had some little means of her own, and for 35 years, he had not contributed a farthing for her support. Living entirely alone, he had given himself up to the task of accumulating money, and this he had done so successfully that at the time of his death his investments were sufficient to have yielded him an annual income of £2000. Nevertheless, for practically a life time he had not known what it was to enjoy a good meal, to be decently dressed, or to have a place in which he could sleep with comfort. One occasionally reads about incidents of this kind, but the genuine miser is usually regarded as a creature of fiction. ♦

* * *

By the following summer the estate had been settled, according to an item that appeared in the Toronto Daily Star on August 31, 1903:

* * *

Settlement of the Hyman Case

Widow and Daughter of Former Wife Propose to Pay Off the Other Claimants

A settlement among the numerous claimants in the Eli Hyman estate is in progress. The estate of the deceased peddler is estimated at $80,000. Mrs. Hyman, the Streetsville widow, and Mrs. Wertheimer of San Francisco, the daughter of Hyman by his first wife, are understood to have arrived at an arrangement whereby they agree to pay off the various claimants and divide the remainder of the estate between them. ♦