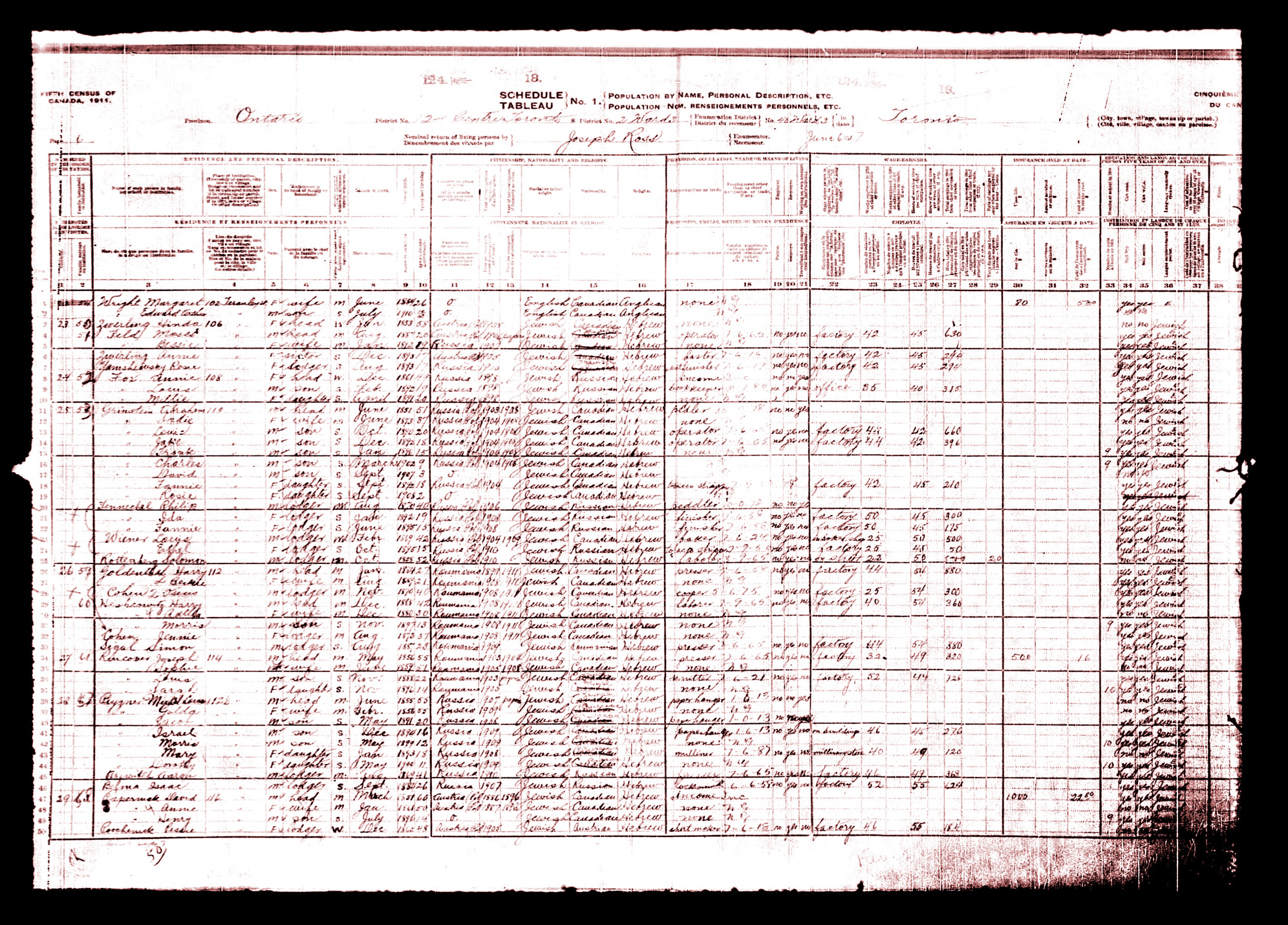

“The Lot of the Census Taker in the Ward is Anything But an Easy One” is the title of the first story; its subtitle is “The Foreigners There Have No Idea of the Months of the Year, and It Takes a Long Time to Convince Them That the Information Is Not for the Tax Collector.”

* * *

From the Toronto Daily Star, June 1, 1911

From the Toronto Daily Star, June 1, 1911

“All right, now, what month were you born in?”

“Such a question! How should I to know? It will be in Russland drei und sixty yahr ago. Beside, I cannot remember. I was only a little kind, und it was in the summer time and –”

“Oh, all right, all right. What month was your wife born?”

“How should I to know? I did not ask her father. I am a poor man and I do not make any money and –”

So it goes. There is a regiment of men in Toronto to-day who need the patience of Job, the wisdom of the serpent, the mildness of the dove, the diplomacy of the French Ambassador at Berlin. They are census enumerators, and whatever your job may be, you may be very thankful that it is not that, anyway.

In the English-speaking sections it was not so bad, but take it in “The Ward,” or wherever the foreigners congregate, and the lions in the path of the seeker after information are legion.

Foreigners Are Timid.

Hostility to the enumerator there does not seem to be, but there is the most amazing ignorance of the things that everybody is supposed to know. They are a timid people, these brown-eyed, simple folk of “the Ward,” and too great insistence, a quick word, or a display of impatience drives them into silence and secretiveness.

Information gleaned by the enumerators is for the use of the Census Bureau alone, and this fact has to be driven home firmly. No man likes to make public the full details of his business, as the census officials ask for them, and if a little shopkeeper in “The Ward” once gets the idea that what he tells the enumerator will be turned over to the Assessment Department as a basis for his next year’s taxes, he loses his tongue at once.

Last night the enumerators for “the Ward” got their fourth and last lesson on their duties, and started out this morning at whatever hour suited their own convenience, around with their big portfolios full of schedules printed on tough paper.

Last night the enumerators for “the Ward” got their fourth and last lesson on their duties, and started out this morning at whatever hour suited their own convenience, around with their big portfolios full of schedules printed on tough paper.

The appearance of the enumerator at the door of a little shop usually reduced the proprietor to a state of something like panic for a few minutes. His diminutive business immediately began to engross the whole of his attention, and he would find himself deeply concerned about the age of eggs or the number of broken biscuits that go for two cents. Eventually, however, the air would clear, and the proprietor be induced to devote a little of his time to the numerous questions fired at him.

Case of Immigrants.

The case of immigrants more or less recently arrived is always the more difficult. Born in some obscure province of Russia, Poland, or Italy, the newly-made Canadian really has very little idea of what is required of him. He knows that he was born “in the Old Country,” but just when or where it is difficult to say. He knows that he came to Canada “in a big ship,” but that was years ago, too. Of English months he has but little idea: something happened “in the summer” or “in the winter,” or he marks his time by means of church festivals, which the Canadian official knows little about; he cannot remember how many weeks he worked last year, or what he got for a week’s work all of the time. is youngest child was born in Toronto. Good, here is something tangible at last, but when? In Purim. What is Purim? It appears to be a church festival or ecclesiastical period of some sort, and the family archives have to be consulted with much shuffling and putting on of glasses before the baptismal certificate can be found (sic).

Hard to Get Answers.

“Do you own this store?” asks the enumerator.

“Ach nein, mister. Once I should to own the store, I would be all right.”

“Then you rent it. How much rent do you pay?”

“I pay — dollars every month and it is too much. Now they have torn down all of these houses (this, by the way, to make room for the new hospital), and all the peoples is gone away, and there is no peoples to come on the shop. I am a poor man. Oi weh! I cannot make any money und –“

“I pay — dollars every month and it is too much. Now they have torn down all of these houses (this, by the way, to make room for the new hospital), and all the peoples is gone away, and there is no peoples to come on the shop. I am a poor man. Oi weh! I cannot make any money und –“

“Oh, that’s all right. Now how much insurance have you?”

Insurance brings up the subject of fires, naturally enough, and the enumerator narrowly staves off an account of the last conflagration that nearly “getot-ed” the whole family, including the cat. All the while beshawled “little mothers” with fluffy-haired grubby little families drop in to buy two cents’ worth of shredded cheese, or a loaf of bread. Then youngsters evince a disconcerting interest in the schedules, and suspend operations on the herring barrel long enough to run stick fingers over the immaculate sheets. It is cram full of human interest, but a little wearing on a man gathering raw material for future statistical abstracts.

Other Difficult Problems.

The Chinamen present a problem that is peculiar to themselves.

The enumerator enters a little laundry, book under arm, and pencil poised. The first question, and the Chinaman emits a noise like an alarmed duck, and dives for the back premises. Chinamen boil out of unexpected corners and flow over the floor. That’s all there is to it. Your Chinaman is about as responsive to questions as one of his own porcelain ornaments, as any policeman will tell you. There is no use talking to him. His yellow face is impressionless, and the enumerator gives it up.

“Have to get an interpreter here,” he says, and the Chinamen, triumphant, vanish behind curtains.

No Interpreters Appointed.

There is considerable soreness among the census men because the Government has so far refused to appoint interpreters to go through the foreign quarters with them.

Capable interpreters, one of them able to speak seven languages, were recommended, but the powers that be have not seen fit to appoint them.

A protest was sent to Ottawa yesterday, and a telegram is eagerly awaited to-day, authorizing the employment of the linguists.

“We can’t perform miracles,” said one enumerator to The Star. “We take oath to give correct returns to all questions as far as possible, but if some people do not speak English and we can’t speak their Babel of tongues, what are we to do?”

A Different System Used.

The Government’s action is strange, too , in view of the fact that the Census Act provides for interprets in districts populated by foreigners. The interpreters do not work on the same system as the enumerators, however. They are employed by the day, and will not be used until there is enough work to keep them busy continuously for some time.

The enumerators are instructed to make a note of the houses where they cannot speak the language, together with the language spoken there. When enough of these have been located the interpreters will be set to work. many of the enumerators in the Ward speak Yiddish, and with this and English they can go a long way.

The enumerators are instructed to make a note of the houses where they cannot speak the language, together with the language spoken there. When enough of these have been located the interpreters will be set to work. many of the enumerators in the Ward speak Yiddish, and with this and English they can go a long way.

If the enumerators had time to look about them, they could get material for many an article or book on the lives of the poor in Toronto. They are busy men, and they have little time to think what some of their dry little entries mean. For instance here is Harry –, just a year and a half out from Russia, who is cheerfully supporting a wife soon to be a mother again, a crippled child of five, and a young and very pretty sister, doing it all on $6 a week, with frequent long periods of unemployment. Not a word of complaint out of Harry, though. All he has is apologies that he can’t get time to learn English.

However, Harry is not a human just now, he is a number, a nose to be counted, a head of the house, though the “house” is only two rooms up two flights of stairs.

Why So Many Questions?

“What does the Government ask so many questions for? Dos weiss ich nicht,” say the enumerated.

“The census doesn’t mean much to the noses that are being counted. These Canadians are funny people, they say. Always asking questions and putting things down on papers. God grant there is nothing bad behind it. It may be as bad as a tax collector or a gas man, for all they can tell, but since the man with the fountain pen seems to be really in earnest about it, it is just as well to humour him.”

Some Manufacturers Unwilling.

In the manufacturing districts the census takers are having their troubles.

Manufacturers misunderstand the situation, and imagine that the Government is trying to open their business affairs to the gaze of the public.

“It’s prying into my private business affairs, that’s what I call it,” said one big factory owner to a South Toronto enumerator, who wanted to know the main facts about his business.

It was only after repeated explaining by the census man that the information was secret, and that after the form was sent to Ottawa, the stub in the book would reveal nothing, that the manufacturer reluctantly gave the desired information.

“We find that the small factory owners make no kick,” said one of the enumerators to The Star. “It is the big fellows who are holding back. It means a big loss of time to us, though.”

Too Much for Him.

There was considerable excitement in the office of Cornelius Ryan, Commissioner for South Toronto, when one of the enumerators, after studying the big book of instructions and attending the meeting at which the men received their final orders, complained of feeling unwell in his head, and immediately lapsed into an epileptic fit.

He is a big, powerful man, and it took seven men to hold him. He frothed at the mouth, roared like a lion, and finally the police had to be called in to take him in an ambulance to the hospital.

The mental strain had been too much for him, and when his books were handed in this morning Mr. Ryan decided to get somebody in his place of a less excitable nature. ♦

* * *

The articles below illuminate the process by which the 1911 census was taken, and the difficulties enumerators had canvassing the vast neighbourhood of “foreigners” who lived in the Ward.

* * *

425 Enumerators Selected for City

Classes for Instruction to Open Next Monday

WORK BEGINS JUNE 1

Five Cents to be Paid for Every Living Person Recorded and Ten Cents for Every Death — Ten Jewish Interpreters Secured.

From the Toronto Globe, May 3 1911

All the enumerators required to take the 1911 census in this city have been recommended for appointment, and next Monday the instruction classes on census-taking will open at convenient centres in the five ridings into which this city is divided. There are 425 enumerators altogether recommended, and they are distributed amongst the ridings as follows: North Toronto, 84, with 88 sub-divisions; Centre Toronto, 62; East Toronto, 48, with 88 sub-divisions; West Toronto, 146; South Toronto, 85.

North Toronto and East Toronto are the only ridings in which enumerators are in some instances, being allotted two sub-divisions. In East Toronto especially, this practice has been adopted extensively. In all the other ridings there will be one enumerator for each of the sub-divisions. Nearly all the enumerators are recommended from their respective ridings.

Commissioners in Toronto.

The Commissioners who have charge of the census-taking in Toronto are: West Toronto, W. O. McTaggart, 979 Bloor street west; Centre Toronto, Thomas Vance, 83 Colborne street; South Toronto, Cornelius Ryan, 77 Victoria street; East Toronto, D. Walton, 47 Simpson avenue; North Toronto, H. M. Ferguson, Canada Life building.

The actual census-taking will commence on Thursday, June 1, and the work must be completed within twenty-one days.

The table of rates and allowances to the enumerators is interesting. Here are some of the items of reward to them: Every living person recorded in the population schedule, five cents; every death recorded, ten cents; for every factory employing five persons or more, twenty-five cents; for every church, Sunday school, college, public or private school, charitable institution and penal institution, twenty cents.

The table of rates and allowances to the enumerators is interesting. Here are some of the items of reward to them: Every living person recorded in the population schedule, five cents; every death recorded, ten cents; for every factory employing five persons or more, twenty-five cents; for every church, Sunday school, college, public or private school, charitable institution and penal institution, twenty cents.

Interpreters in Centre Riding.

The heaviest work will devolve upon Commissioner Vance in the Centre riding, which includes the “Ward.” The multiplicity of nationalities there presents a formidable difficulty, and a number of interpreters will be used. Ten Jewish University students will assist in the enumeration of the Jewish population.

Toronto’s population in 1901, when the last census was taken, was 208,040, and was distributed among the five ridings as follows: North Toronto, 40,983; West Toronto, 44,991; Centre Toronto, 43,861; East Toronto, 40,097; South Toronto, 38,108.

A big increase is expected in West Toronto, especially, with this coming census. Ten years ago there were only eighty sub-divisions in that riding; according to the arrangement this year there are 146. There are at least 700 people in a sub-division, so that by multiplication it will be seen that West Toronto’s population this June will be found to approximate 100,000. ♦

* * *

Census Men in “Ward” Grow Grey with Worry

Summonses to Be Issued if Foreigners Do Not Give Information Desired

From the Toronto Globe, June 5, 1911

Instead of growing wealthy through the large families which inhabit “The Ward,” the luckless census enumerators are fast becoming grey with worry. Not one or two visits do they pay to each house, but more often ten or a dozen, and every time they find some new roomer or member of the family. The population of “The Ward” simply refuses to aid the census men in any way, regarding them as unnecessary evils, and shutting its doors upon them.

“Unless some of them disgorge the true numbers of their households by 3 o’clock to-morrow,” said Mr. G. Vance, “they will find themselves in the court in the morning. We don’t want to issue a single summons, but we intend to get the information, and if people won’t give it to us we must simply make them.”

Despite their worries, occasional iridescent flashes of unconscious humour lighten the toils of the workers. One stalwart Jew refused to give any information because the enumerator would not show his button, probably thinking the searcher to be related to the gas meter man.

Another, an Italian woman, refused entrance, declaring volubly that there were neither knives nor revolvers on the premises, and that her husband had not a single keg of beer concealed.

Conscription evidently ranked supreme in the thought of one lusty Italian family, the head of which was in mortal fear lest the enumerators should be on the lookout for likely soldiers of the King.

With very many foreigners, particularly Chinese, thee is a great reluctance to give correct information. The enumerators ascribe this to the fact that doubtless a large proportion have either been smuggled in or else entered in violation of the immigration laws, and consequently fear that they will be deported. Mr. Vance wishes it to be stated that no such result will follow.

As things are at present, every likely boarding-house has to be watched incessantly, which naturally wastes both time and money. ♦

* * *

Hauled into Court to Tell her Birthplace

The First Woman to be Summoned for Refusing to Answer Census-Taker

From the Toronto Daily Star, June 8, 1911

The first census enumerator to ask the court to compel anyone to give information is Joseph Rose, and it was a woman, a Russian-Hebrew, who refused to answer one question. It was Mrs. Annie Fox, of 108 Teraulay street, and she managed to supply all information demanded except the country she was born in.

“I guess she was frightened out of her wits,” explained Jacob Cohen in an effort to make things as easy for her as possible. “Perhaps she thought she was still in Russia.”

Magistrate Kingsford placed the woman in the witness box, confronted her with the enumerator and repeated the query.

“Where were you born?”

The woman had lost all desire to conceal facts and shout out a few frightened sounds.

“She says it’s Russia,” Jacob Cohen interpreted.

“Now run home,” admonished the court, and the woman seemed to understand. ♦

* * *

See also The 1911 Census is a powerful tool