In Devil in the White City, a riveting page-turner that reads like a murder mystery thriller, Erik Larson resurrects the legend of a forgotten American psychopathic mass murderer, the cold-blooded H. H. Holmes, and overlays it atop the equally dusty story of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, one of the most impressive achievements of gilded-age America.

In Devil in the White City, a riveting page-turner that reads like a murder mystery thriller, Erik Larson resurrects the legend of a forgotten American psychopathic mass murderer, the cold-blooded H. H. Holmes, and overlays it atop the equally dusty story of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, one of the most impressive achievements of gilded-age America.

Satisfying the modern appetite for realism, the book falls into a hybrid literary genre, combining the narrative techniques of the suspense novelist with the intense realism of the non-fiction documentary work. “However strange or macabre some of the following incidents may seem, this is not a work of fiction,” the author advises in a preliminary note, adding that all quoted material comes from documented sources.

The author has also hobbled together two distinctly different subject matters, each normally of a separate stature and requiring distinctive treatment. In Larson’s hands, the chapters dealing with the fair have an ominous undercurrent of death, decay, fright and morbidity — the very traits that we come to associate with Holmes. Thus unified in tone, this Frankenstein of a book lurches forward with a peculiar, uneven gait, carrying the enthralled reader in its vice-like grip for 390 pages.

Dr. Henry H. Holmes, whose real name was Herman Webster Mudgett, was a brazen serial killer who, like the society around him, embraced many of the modern conveniences of his day. As all of Chicago was churning with excitement at the prospect of hosting a magnificent world’s fair, Holmes designed and built a tourist hotel near the fairground, at 63rd and Wallace. Nicknamed the castle, it was a dark gothic edifice with long narrow hallways, odd-shaped rooms, a soundproofed vault, hidden passageways, and leaden chutes through which large objects could be dropped into the cavernous basement, where Holmes had installed a coffin-shaped kiln hot enough to melt glass. (It was for a glass factory, he explained to the curious.)

Dr. Henry H. Holmes, whose real name was Herman Webster Mudgett, was a brazen serial killer who, like the society around him, embraced many of the modern conveniences of his day. As all of Chicago was churning with excitement at the prospect of hosting a magnificent world’s fair, Holmes designed and built a tourist hotel near the fairground, at 63rd and Wallace. Nicknamed the castle, it was a dark gothic edifice with long narrow hallways, odd-shaped rooms, a soundproofed vault, hidden passageways, and leaden chutes through which large objects could be dropped into the cavernous basement, where Holmes had installed a coffin-shaped kiln hot enough to melt glass. (It was for a glass factory, he explained to the curious.)

How ironic that this human monster — equal parts Sweeney Todd, Ted Bundy, Hannibal Lector and Josef Mengele — could make himself so irresistibly charming to women. “He broke prevailing rules of casual intimacy: He stood too close, stared too hard, touched too much and long. And women adored him for it,” Larson writes. By conservative estimates, he murdered dozens of unattached females lured to the big city by the fair. Numerous women who became his fiancees disappeared, as did some of their sisters; they ran off with someone else, Holmes would explain. Men, especially bill-collectors, were also charmed by him; he was adept at floating dozens of creditors simultaneously, like a juggler keeping balls in the air. He was a confidence man par excellence.

In several cases he convinced trusting friends and lovers to buy insurance policies, naming him as beneficiary: a fatal mistake. Accidents always seemed to be happening near him; his arsenal included poison and suffocation: he also gassed tourists to death in their sleep. Possessing the unquestioned authority of a medical degree, he would sometimes strip the flesh off the cadavers of his victims, bleach the bones, and sell the skeletons to medical schools. Despite a growing missing persons list, some of whom were last seen at the world’s fair, the police were too disorganized to conduct the rigorous investigation that was required.

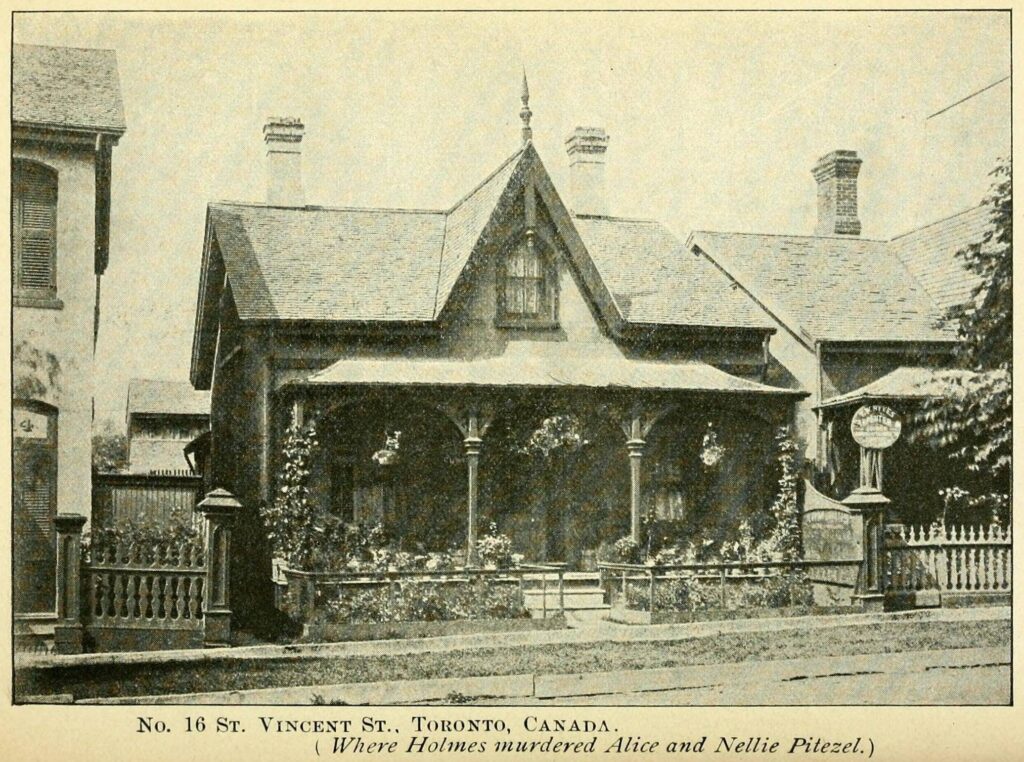

Until Detective Frank Geyer, that is. Two years after the fair, the shrewd gumshoe sensed that Holmes had plotted an insurance scam with a partner, then killed the partner’s wife and two children so he could keep the money for himself. As Geyer discovered, Holmes had dragged the poor children to Indianapolis, Detroit and then Toronto, where he gassed them in a trunk and buried them in the dirt cellar of a rented cottage near what is now College and Bay streets. After Geyer dug up the corpses, the story made front-page headlines across the continent; by then, Holmes was rightly being referred to as “the Chicago monster.” He eventually was hanged.

Until Detective Frank Geyer, that is. Two years after the fair, the shrewd gumshoe sensed that Holmes had plotted an insurance scam with a partner, then killed the partner’s wife and two children so he could keep the money for himself. As Geyer discovered, Holmes had dragged the poor children to Indianapolis, Detroit and then Toronto, where he gassed them in a trunk and buried them in the dirt cellar of a rented cottage near what is now College and Bay streets. After Geyer dug up the corpses, the story made front-page headlines across the continent; by then, Holmes was rightly being referred to as “the Chicago monster.” He eventually was hanged.

Alternating chapters of this chilling narrative deal with the massive achievement of the so-called “white city” — the monumental fairgrounds built in less than two years by a cadre of architects that included Daniel Hudson Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted, and involving a supporting cast of real-life personalities from Buffalo Bill Cody to Thomas Edison. Larson is successful in depicting a city so giddy with the notion of progress, scientific advancement, civic growth and the optimism of the gilded age, that it had become an unregulated jungle where a cunning beast like H. H. Holmes could operate with seeming impunity.

Larson deserves enormous credit for retrieving this important piece of social history. Although he takes some dramatic liberties, he maintains his unwritten pact with the reader by remaining loyal to the documented truth. If his depiction of Holmes seems as thin in spots as a cardboard villain from Dickens, it’s the result of a lack of information. Larson has done an excellent job with the limited material at hand; obviously intoxicated with the story, he deftly polished each of its facets until the whole became as sparkly and shiny as a jewel. ♦

© 2003, 2013, 2025

Photo of 16 St Vincent St (now Bay Street near College) courtesy UrbanToronto