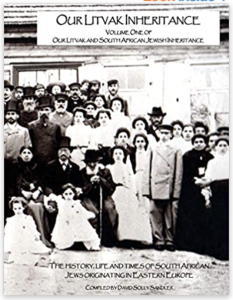

Our Litvak Inheritance, Volumes One and Two of Our Litvak and South African Jewish Inheritance, compiled by David Solly Sandler. Three large-format paperback volumes with b&w illustrations , published 2016.

Like most South African Jews, Sandler’s ancestors emigrated to South Africa from Lithuania between 1880 and 1920. A thorough historical researcher but not what he would call a writer or story teller, Sandler was urged to write a family history but chose instead to compile this pair of large heavy volumes (with a third promised soon). Each presents an ordered and lightly curated collection of articles, stories and histories focusing on the themes of life and history in Lithuania, emigrating to South Africa, and life and history in South Africa from (generally speaking) 1880 to 1950.

Like most South African Jews, Sandler’s ancestors emigrated to South Africa from Lithuania between 1880 and 1920. A thorough historical researcher but not what he would call a writer or story teller, Sandler was urged to write a family history but chose instead to compile this pair of large heavy volumes (with a third promised soon). Each presents an ordered and lightly curated collection of articles, stories and histories focusing on the themes of life and history in Lithuania, emigrating to South Africa, and life and history in South Africa from (generally speaking) 1880 to 1950.

This is truly a Reader’s Digest-type compilation of materials that are in some cases already on library shelves; also some previously unpublished items and published items that would be hard to find. They include The Jewish Settlement of Keidan by Boruch Chaim Cassel; extracts of The Keidan Yizkor Book; The Yizkor Book of Rakishok and Environs and similar fare for other shtetls; excerpts from several books and accounts of family history; reprinted articles such as Rony Golan’s Jews Expelled from Kovno in WWI which first appeared in this journal; and sundry other pieces.

This sprawling mixture begins with a timeline of Jewish history that runs from 3800 BCE to 1918. Cassel’s long essay on The Jewish Settlement of Keidan likewise begins in ancient times, although in this case the Jews don’t make an appearance in Lithuania until the 10th century, perhaps as late as the 12th century. The region was late being Christianized and was rife with Crusader wars. Following the pattern that was prevalent in Europe during that era, the Jews were expelled in 1495 and allowed to return in 1503; many found protection in Poland in the interim, and long after. This is a fascinating essay, bearing mentions of regional place names such as Kazdan (a village) and Abela (a river) that, perhaps significantly, are carried by Jews even today. The book carries numerous other pieces about Keidan, reflecting the settlement’s importance in Lithuanian as well as Lithuanian Jewish history.

Besides Keidan, the section on Life in The Shtetl offers pieces on Linkovo, Seta, Rakishok, Pumpenai, Pasvalys, Panevezhys as well as Libau Latvia and Goldingen in Courtland (sic) Latvia. The section on the Holocaust offers pieces representing 21 towns, including the additional towns of Joniskelis, Kretinga, Pokruojis, Rietavas, Saukenai, Seduva, Seredzius, Ukmerge, Zasliai, Zeimelis and Zeimiai. One might observe that, despite the heft of these volumes, their coverage is sporadic and far from encyclopedic.

Typically, the piece about Goldingen (as told to Eric Rosenthal by Moshe Leib Nurick) focuses on the late 19th century and is filled with vivid first-person descriptions and delightful vignettes, such as this account of a boy’s first experience with cheder:

“The cheder was run by a retired pedlar who, for that reason was nicknamed Josele der Kremer. I was about four years old and there were between 60 and 70 children in the crowded shtiebel. Josele was a little man with a white beard. On the first day of cheder, to our astonishment and great delight, he threw handfuls of sweets onto the table. The object, we were told, was to make learning and the study of Torah sweet.”

Nurick also recalls the first time he saw a bicycle. “It was a German machine of the penny-farthing type. It created such a stir in the village that streams of children were running down the street after the rider — myself included.” Such recollections are the very stuff of history.

Whereas Volume One focuses on the Jews of Lithuania, Volume Two deals with the Jewish experience in South Africa, from the first Jewish settlers of the 1820s through the eras of the Second World War and Israel’s War of Independence. Kimberley, Natal, Johannesburg, the Orange Free State, the Transvaal and other regions are covered with a wide assortment of reprinted articles and essays, most well illustrated.

A plethora of historical material deals with community organizations, personalities and related subjects. In some cases Sandler neatly “cuts and pastes” images of newspaper articles that he has retrieved: the depth of his curiosity seems matched only by his determination as a researcher. The book even includes a reprint of the 1930 annual report of the South African Jewish Orphanage — later called Arcadia — which lists thousands of names of supporters and is, therefore, a significant resource for genealogists.

It turns out that Sandler, whose mother died at the tragically young age of 34, spent most of his childhood (from 1954 to 1969) in Arcadia. “I think the fact that I did not grow up in a traditional family environment must have triggered something in me to find out more and more about my family and ancestors,” he explains. The result is a bountiful omnibus that offers numerous rare and fascinating pieces.