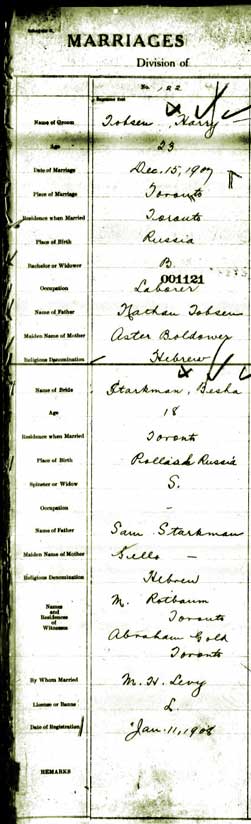

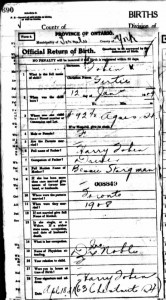

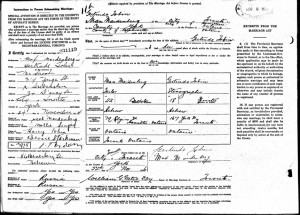

Prelude: Bessie (Besha) Starkman, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, married baker and driver Harry Tobins in Toronto in 1907 and gave birth to daughters Gertrude in 1909 and Lilly (Leah) in 1911. They lived at 92-1/2 Agnes (Dundas) Street in 1909 and 63 Chestnut Street in 1911. In 1912 an Italian immigrant named Rocco Perri rented a room in their home and conducted an illicit romance — and eventually a criminal partnership — with his landlady.

Prelude: Bessie (Besha) Starkman, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, married baker and driver Harry Tobins in Toronto in 1907 and gave birth to daughters Gertrude in 1909 and Lilly (Leah) in 1911. They lived at 92-1/2 Agnes (Dundas) Street in 1909 and 63 Chestnut Street in 1911. In 1912 an Italian immigrant named Rocco Perri rented a room in their home and conducted an illicit romance — and eventually a criminal partnership — with his landlady.

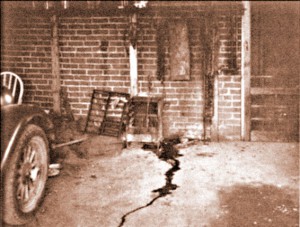

Throwing conventionality to the wind, Bessie ran away with Rocco and assisted him in building a lucrative bootlegging empire said by some accounts to be second in North America only to Al Capone’s; she was said to have a superlative business sense. But the couple’s second sense failed them that day in August 1930 when, returning to their home in a nice neighbourhood of Hamilton, Ontario, they drove into a trap and Bessie was gunned down in the garage. Her murderers were never apprehended.

The following colourful and somewhat sensational account by Frederick Griffin of her funeral was published in the Toronto Star of August 18, 1930. Griffin estimated that a mob of some 20,000 people swarmed the Perri home that sweltering day and followed the cortege to the local Jewish cemetery where Bessie, who was the common-law but not legal wife of Perri, was laid to rest in a simple grave alongside the fence under the watchful eye of a visiting rabbi.

* * *

Grotesque Ceremony Becomes Free-For-All of Morbid Curiosity

Twenty Thousand Mill and Fight to See Bessie Perri’s Magnificent Funeral

HEARSE BREAKS DOWN

Regal Coffin Buried in Orchids — Consort and Daughters Faint Under Strain

by Frederick Griffin

Hamilton, Ont., Aug 17 (1930) — It took only a split second to kill Bessie Starkman, consort of Rocco Perri, in the Perri garage near midnight last Wednesday night. It took over two hours to stage her strange funeral this blazing Sunday afternoon.

Hamilton, Ont., Aug 17 (1930) — It took only a split second to kill Bessie Starkman, consort of Rocco Perri, in the Perri garage near midnight last Wednesday night. It took over two hours to stage her strange funeral this blazing Sunday afternoon.

It was held against a background and amid mob scenes of strange savor that were surely without precedent on this side of the border.

It was an amazing climax to the career of this woman of forty — which was her actual age, I’m told, although she was a grandmother — whom police credit with being a woman of organizing ability and of force of rule in her invisible kingdom unique in Canadian annals.

Legends may well arive about this dramatic and dynamic Jewess who mated with an Italian in a liaison of love and sinister business which ended only when a killer’s gun smashed the partnership.

Chimes Sound Knell

It was exactly two o’clock — for I heard, as I watched the grandfather’s clock in the adjacent dining-room strike the soft liquid chimes — when the rabbi lowered the casket lid on Bessie Starkman’s face in the flower-choked room of the Perri home, where she had lain in state, like a princess, for three days and nights while ten thousand people filed in to see her.

The dog — the big German police dog which had been so queerly quiet the night of the killing — was, I remember, barking. Its baying came with muffled force from the cellar below where it was now held.

And Jewish women and dark Italian women were softly wailing in the stifling, scented room, while outside on Bay Street between Bold and Duke Streets, 5,000 people milled and reared in their eagerness to get in and look.

The roar of them came in like the shouting of impatient bleacherites wanting the gates opened for a big game. Police and husky Italian men held the door forcibly against their entry.

It was exactly four o’clock when the casket of bronze and silver steel costing, it is said, $3,000, was lowered into the earth by the side of the fence by the edge of the orthodox in the tiny cemetery on Hamilton mountain to which it had been carried.

Slowness an Agony

A strangely long four miles had lain between the quiet last scene in the shadowed front room and this open-air riot in which hundreds surged over graves and fought for close-up views. To Rocco Perri and the two dead women’s Jewish daughters who rode with him in a big car behind the hearse, it must have been an agony of slowness.

I hold no brief for Rocce Perri, although he made me welcome to his home. It was he who made his partner’s funeral a public pageant. He placed taxi-cabs at the disposal of every Italian who sought to attend. But I do not think that he dreamed that the strain would have been so great.

Blocked on Herimer Street for nearly half an hour by the traffic jam which was created, sightseers who thronged the route crowded round his car and peered at him as at a curiosity.

Every time the procession halted they gathered round to look in at him.

And then, after climbing the steep highway of the hill, the motor of the hearse broke down on the plateau, more than a mile from the cemetery. That was the penultimate straw of the afternoon: the morbid crowd at the cemetery who fought for close-ups was the last.

Broken by the Strain

Small wonder Rocco Perri’s nerves gave way and that he had to be literally carried by his friends, who made a flying phalanx to get him through out of the burial ground so that he did not see Bessie lowered into the ground.

Small wonder that Bessie’s two daughters, melancholy figures in black who had been registering a degree of grief such as I had never seen, had to be borne aside in a semi-comatose state of bewilderment and woe.

But the story of the afternoon as I saw it had better be told in sequence.

It was shortly after one o’clock when, with Athol Gow of The Star staff, I went to 166 Bay Street, Rocco Perri’s home. This is a fine residential street of a quiet type, something like St. George Street, Toronto. It is on the edge of one of Hamilton’s best districts.

Perri’s house, although large enough inside, is semi-detached, with a very high veranda on which opened the bow window of the room in which Mrs. Perri, as she was popularly known, lay.

Ten Thousand Call

At this time the street was not yet thronged, although there was a crowd. But an endless procession filed up the veranda steps and into the house to look at the murdered woman. They had been coming, I was told later, by Mrs. Mike Sterge, Perri’s sister, since the body was brought home Thursday evening at eight o’clock up to the time when the doors were closed about one thirty Sunday afternoon. They had arrived as early as 7:30 and 7 every morning since and as late as 2 and 3 o’clock in the morning.

Italians came from Buffalo, Welland, Niagara Falls and other parts of the Niagara peninsula. Hundreds of non-Italian people came also. In the crowd I saw there were many Anglo-Saxons.

It was Mrs. Serge who put the number of people who had called at 10,000.

Athol Gow and I, finding it impossible to get in at the front, entered by the back door. We went up the lane up which the Perris had driven on the night of the killing and into the garage. I had had the impression that the garage was back from the house. It is really part of the house, or rather built up against the rear of the house.

Garage is Crowded

Mrs. Perri was shot down inside the garage as she walked to a stairway (also inside the garage) that leads up to the kitchen door.

Mrs. Perri was shot down inside the garage as she walked to a stairway (also inside the garage) that leads up to the kitchen door.

There was such a crowd in the garage, looking over the two cars, examining the place on the wall where the shot had struck, that I had little chance to look around.

We went up and entered the immaculately white kitchen. This proved to be the temporary headquarters of the obsequies. It was crowded with Italians, men and women. Tea cups were in evidence. The pall-bearers, young Italians wearing tuxedos, black bow ties, soft white shirts and gray silk gloves, stood waiting.

I was given their names. They were Joe Romeo, Tony Serge, Anthony Marando, Jules Sperazze, Matthew Rastivo and Sam Calubro, all of Hamilton, the first three cousins of Rocco Perri.

I was also given the names of the chief mourners: Rocco Perri, Mrs. Gertrude Maidenberg and Mrs. Lily Shime, daughters of Mrs. Perri, and their husbands: Mrs. Stallarin from Detroit, niece of Rocco Perri; Mike Serge and his wife, the latter Rocco Perri’s sister; Joe Serge and his wife, Joe Romeo and his wife, Frank Catanzrita and his wife and Mike Romeo and his wife.

Attends from Jail

Mike Serge, brother-in-law of Rocco Perri, who had been sent down for three months the day of the killing for having alcohol in his possession, was released temporarily to attend the funeral. He was driven to the house from the jail by Jim Pealrie, sheriff’s officer, who took him away again after the funeral.

Pealrie was later to prove a further friend in need, for it was his car which towed the broken-down hearse on its last lap to the cemetery.

Along the hall of the house ran the following rooms — the kitchen (as described), the dining room, a sitting room and the drawing room at the front in which Mrs. Perri’s body lay.

In the dining room sat a circle of Jewish women in black dresses.

In the middle sitting room, from which wide doors opened on the front room, only now they were blocked with the bank of flowers, sat in a circle the Italian women mourners. Some of them were old women, wearing black shawls. Others were young comely women in mourning.

On Gloomy Vigil

In this room, gloomy as if it were late twilight with the lamps not yet lit, sat Rocco Perri in an armchair. He proved much smaller than I had imagined, a short, dark man, inclined to stoutness. Athol Gow introduced me. He murmured something. I did not catch it.

I went into the front room. This was the room of lying-in-state. A most pleasant room, I should say, under normal circumstances. It glowed with rosiness. The window drapes were rose. Rose shaded candles lights glowed against the walls panelled with gray silk paper. There was a rose-shaded standing lamp. And above the face of Bessie Perri another rose lamp was bracketed to the casket lid, the upper third of which had been hinged back open.

This lamp glowed from beneath a canopy of white gauze-like lace through which the face of the dead woman showed softly. Besides these were three candles burning in a silver candles stick at her head.

The general effect was a serene whiteness. Mrs. Perri’s face, pale, well-cut, strong, as though carved in stone, showed — though the hair was hidden — from a bed of pure white silk, crinkled, if that is the right word. The lid was covered, on the underpart which was to close over her head, with this same white effect.

Coffin Concealed in Flowers

The massive coffin of bronze, with heavy silver steel trimmings, was scarcely to be seen, hidden, as it virtually was, with flowers.

What flowers! I am not an expert in funerals but, personally, I never saw anything to equal them. Athol Gow and I, figuring conservatively, as we thought, placed the value of them at $3,000. Maybe we were high. Maybe we were low. At any rate they were magnificent. There were over a hundred wreaths. Orchids were a commonplace.

At the head of the coffin was a magnificent pillow of mixed flowers, orchids, roses, gladioli and other blooms, literally hundreds of them.

It was from Rocco Perri.

Across it there was a wide ribbon of gauze. And on it in letters of gold were the words, “To my wife.”

On top of the coffin was a chair, as large as a child’s chair, of mixed roses. I do not know who sent it. Here and there on the magnificent wreaths, there were pure white doves of peace poised in flight. There was a harp of flowers, largely white lilies almost as tall as a small man.

I cannot begin to detail the wreaths. Flowers flowed up and around the coffin and up the walls until they were the height of the candle light fixtures.

Only in the heart of the room was there a vacant space leading to the coffin. There were two rows of light chairs with red leather seats.

I entered the room just as the last of the sightseers were going out. I got in in time to see Sardo, the guardian of the room, check a young man who lifted the veiling from Mrs. Perri’s face to gaze close-up beneath. He said roughly, “Don’t do that!” as he caught the man by the arm and showed him out.

Women stood crowded on every step of the stairs and along the narrow hall.

Outside, people were on the veranda. They thrust hands through and raised the blinds so that they might peer in.

Suddenly there were shouts in the hall. “Close the doors. Close the doors.” There was a big commotion outside. Italians inside held the front door forcibly against people pushing and clamoring to enter.

Quite suddenly Rocco Perri appeared. “Close the door tight,” he cried. “Plenty have seen. It is enough.”

He looked frowningly outside. He came into the room whee Bessie lay. There was a clamor which broke strangely in this room where the dead woman lay. In a moment the room which had been empty, was filled with people who had been in other rooms of the house. Italians and Jews. I found myself pressed back against the flowers. There was a terrific undercurrent of excitement.

Daughter Faints

I had scarcely begun to notice a slight girl in black when, all of a sudden, with a moan, she pitched fainting at my feet.

It was Mrs. Maidenberg, Mrs. Perri’s daughter. The people gathered her up and carried her out.

The clamor outside at the door grew stronger. Itw as necessary to watch the window lest people climb in that way in their eagerness to see the body.

“Phone for the police. Get the police.” The word was passed through the Perri home.

Peculiarly enough, the Hamilton police seemed up to this point to have ignored the occasion.

Shortly after one-thirty Deputy Chief Ernest Goodman and a number of policemen arrived. Already a number of Italian men outside on the veranda and inside the door were holding at bay the press who surged up the steps in an effort to enter.

The police tried to drive the people back from the door and off the veranda. There was scuffling, shoving and shouting.

Rabbi Arrives

The time passed like this, in clamor. The rabbi arrived. He was Rabbi Isadore Freund of Goldsboro, North Carolina, a former rabbi of the Anshe Sholom synagogue of Hamilton, who, I understood, was in Hamilton on a visit. He proved a young man, with glasses, wearing a blue suit and a gray fedora.

It was almost two o’clock. He entered the room and went over to th ebier. The room which had been again empty filled again in a moment. Rocco Perri came in. The two daughters of Mrs. Perri, wilting, eyes closed, moaning, seemingly only half conscious, were led down the stairs by their husbands and half carried into the room.

Rocco Follows Jewish Custom

“Where’s Roc’s hat?” The call came out of the room and was passed along. The hat was forwarded. Rocco Perri put it on. This Italian was conforming to Jewish custom. Other men in the room put on hats. Some of the Italians stood bareheaded.

The two daughters went forward nd took a last look at their mother’s face. The sound of their low moaning came out to where I stood back on the second step of the stairs.

Rocco Perri then stepped forward. He stood for a moment with his two hands on the side of the casket. His shoulders shook up and down, violently. But he made no sound. He stood thus for a moment. Then he turned away. He sat down on a chair between the two daughters. Thus he sat during the service.

Someone switched on the big electrolier of cut glass which hung from the center of the ceiling. The room which been so rosily dim was flooded with a brilliance of harsh white light.

The heat was almost unbearable.

The three tapers which burned at the head of the bier of Mrs. Perri were guttering to a finish in their silver stand when Rabbi Freund in a low voice that was scarcely audible where I stood, began the reading of the Psalm: “I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills.”

It was jus at this moment that the sound of the clock’s chimes came with golden mellowness from the next room. And for the first time, in he comparative silence which the murmuring of the mob outside did not quite drown, I heard clearly the baying of the police dog prisoned in the basement.

It was not a howl of lament, but a savage barking.

Service Overrides Interruptions

The reading of the rabbi went on uninterrupted by shouts of “Order! Order!” as there was a fresh commotion at the door. Repeatedly during the service there were these interruptions.

The rabbi read: “Thou art strong and we are weak. Thou art wise and we are simple. Thou art infinite and we are finite . . . Hear thou us, O Father, for we are sorely stricken. . . . O God the Father in They encompassing love . . . forgive our sins for there is no man that liveth and sinneth not . . . . Man is like a vanity. His days are as a shadow that passeth away . . . . Thou bringest our years to an end as a tale that is told . . . . “

“Order! Keep that door shut!!” Every now and then these loud cries punctuated the solemn reading.

Then in Hebrew the solemn voice recited the prayer Kel Moleh Rachmin, “God full of pity.”

There was no cantor and the rabbi did not deliver an oration, but otherwise, I was told, the simple service conformed to the regular reformed ritual of the Jewish faith in which Bessie Starkman-Perri had been born.

Bessel Bas Shiman

And the rabbi referred to her in the Hebrew, according to custom, as Bessel Bas Shiman, which, being translated, means Bessie the daughter of Simon.

It was Bessie the daughter of Simon, the Jew, and not Bessie, the partner of Rocco Perri, the Italian, whom the young rabbi buried. But he buried her by the fence, by the edge of the orthodox, beneath a withered tree of thorns.

Not for Bessie Starkman at the last was what warmth she might have had from sleeping completely within the ranks of her race and faith.

At least she was buried with a show of the ancient ritual in consecrated ground in the little dishevelled cemetery of Ereve Zedeck, which means Land of Righteousness, on the top of the mountain.

But of that later. The service ended, there was the problem of the parade. Twelve open cars had been ordered for the flowers but only four or five were to be seen when I went outside on the veranda. The others had been blocked away back. The street was literally chocked with people. Below there was a veritable tapestry of upturned faces. People swarmed on the street, on the sidewalks, on the lawns. People were on the tops of the funeral cars, up trees, on verandas, on the very roofs of the verandas.

Only on the black hearse in front of the house there were no people. But they milled around it.

There was an animal sound from the mob, a kind of anticipatory “Ah!”, long drawn, when the front doors opened and some of us went out, like the sound I remember hearing a Mexican mob make at a bull fight.

Police Fight in Hearse

Police fought to make a narrow land down to the hearse.

Men began carrying out the magnificent wreaths. The crowd craned, josttled, struggled, murmured in a thousand exclamatory accents as the long procession of flowers went down to the cars.

The cars were piled high with flowers. The petals from them broke and strewed the steps of Bessie Perri’s home as far as the hearse and beyond.

And then at last the casket came out. Women, especially, exclaimed audibly at its magnificence. One could hear them. For the first time I really saw it. It was a grand coffin indeed. There was no inscription, no marking of any kind, which I understood, I hope correctly, is according to Jewish custom, although the casket was not, since the rules call for a casket of wood. But this was a costly one of bronze and silver steel.

The casket was put in the hearse. The police managed to hustle Perri and the two duaghters to their car. But then the crowd, surging in around, cut off all the rest of the mourners. I was caught in that crowd myself so I know what it was like. The women mourners of the Perri family broke down and cried as they felt themselves crushed and borne along by the clamoring people who pressed to get close to the hears and Perri.

Procession Starts at Last

It was half an hour before the last of the mourners were got into cars and started on their way to the cemetery. The few police were helpless to handle the mob which had gained possession before they came.

But at last the procession started and wound its way along Bay, along Herkimer, up the Jolly cut and the mountain road to the cemetery. There was a half-hour blockade on Herkimer during which we did not move an inch and during which scores thronged gaping around the car in which Perri and the two daughters sat with their husbands and Frank Romeo, a friend of Perri’s, in the driver’s seat.

I don’t know how many people lined the route of the procession but, judging by crowds I have known, I know I am underestimating if I say twenty thousands. Every yard of the more than four miles held spectators and in some places they were three and four deep. Even along the mountain road there were crowds and along the plateau there were thousands of people.

It was up here that the hearse broke down, stopped and had to be towed. It must have taken twenty minutes to cover the last mile. Every few minutes there was a stoppage and the tow rope had to be adjusted. The affair became tedious, tiresome.

Ritual Act Unperformed

But at last the cemetery was reached. It is a small plot, not much bigger than a good-sized back yard, the sparse grass burnt to a crisp shagginess. It was enclosed by a wooden picket fence. Inside the gates was the Holy House where ritual of sanctification is performed over the Jewish dead.

Here, I was told, the bodies of the dead are taken from the coffin, washed and made holy.

This act was not done in the case of Bessie Perri.

This Holy House was a small frame shack, painted a weak brown with green edging to the roof.

It was bare inside except for a rusty stove on which the water of sanctification is heated for the orthodox.

It was jammed with people. Hundreds of people already milled in this bleak little garden of the dead.

In the Holy House was a small wooden lectern with a book of Hebrew script open ready for the rabbi’s reading and above it four candles burning.

The casket was carried in. The lid was opened. Once more for a moment the dead face of Bessie Perri showed briefly. There was considerable argument in loud voices around the casket. The Jews who seemed to have taken charge when it entered the cemetery seemed angry. When the casket was opened the Italian pall-bearers made the sign of the cross. I heard Jewish women clustered behind me speak excitedly.

Defile Graves of Dead

The casket lid was closed. There were shouts, “Get it out of here. Get it out to the grave.” The rabbi did not read from the Hebrew book standing ready on the lectern. The casket was raised and carried forward.

The bearers had literally to fight their way to the grave. The people thronged around, trampling over graves, defiling this holy place of Jewish dead. People climbed up and stood on precarious points of vantage on top of the picket fence. Men scrambled up the trees that intermittently lined the fence.

The chief mourners were cut off. I caught a glimpse of Perri and the two daughters, of this one and that one trying to break his way through.

The crowd, avid for a close-up, would not give way. The proceedings grew grotesque. There was loud shouting. Around the grave there was literally a fight as people struggled to get close. There was pushing and shoving such as you’d see in a football scrum, the angry shouts of men, the attempts of the cemetery workers to make a clear space, the cries of women being pushed and hurt, the wailing of the female mourners. It was a miniature bedlam. There were no police present. It was a free-for-all of morbid curiosity. I have never seen anything so pitifully terrible.

I felt sorry for these Italians who had come to bury this woman who had been murdered. They were so helpless in this ghoulish jamboree. And the heat added to their misery. The sun beat down torridly. The little graveyard seemed hot as a blast furnace. There was not a breath of wind.

Perri Overcome

Rocco Perri and his friends fought their way to the graveside just as the casket, fixed in the lowering apparatus, had sunk flush to the level of the ground.

Perri had no sooner reached this objective than he lost all control. He pitched forward and almost fell. The man was quite obviously all in from the strain. His face was working. Friends got around him and battered the crowd back to give him air. They pulled his collar loose, ripped back his shirt to let the air on his chest, and then, surrounding him, bore him out towards his car, calling for water. They helped him and pressed his face, murmuring what were evidently endearments. Finally they got him to the car, and got him in. There he lay back, exhausted. Thus he stayed while the body of Bessie was eventually lowered. And after he returned home a physician was called in, for he was said to be in bad shape.

While he was being carried out Mrs. Maidenberg and Mrs. Shime, the daughters of Bessie Perri, went down and out. They both keeled over, wailing, and fainted. A couple of other women in black fainted. The crowd milled and mobbed around them. There was pandemonium. A little Englishman started shouting, “Give the ladies air” and went slightly berserk, flailing with his fists. At least his methods got clearance for he cut a semi-circle by sheer force.

The women were worked back from the graveside. There, surrounded by a complete circle of the curious, they stayed crying and wailing. I have never seen such an extreme manifestation of distress and woe.

In the meantime, surrounded by a press of people that almost pushed him and the cemetery men into the grave, Rabbi Freund read in Hebrew the Kadish and committed the body to the ground.

Earth in a white bag was placed on the dead woman’s face. The casket was lowered into a wooden box. A lid was placed over it. Earth was thrown in. Soon the men were shovelling in sturdily.

And thus Bessie Starkman-Perri was buried.

The twelve car loads of flowers vanished when the procession reached the grounds since Jewish custom bars flowers from the cemetery, according to my informant. They were, I understood, to be sent to the Hamilton hospitals, by Rocco Perri’s orders.

As I drove away I noticed that several patches of dry grass along the sides of the road were ablaze. Men from nearby homes were fighting the flames. It was the last strange note. ♦

4 comments for “20,000 gawkers swarm Bessie Starkman funeral, 1930”