Born in 1887 to Jewish parents in Kalamazoo, Mich., American novelist and playwright Edna Ferber was a hardworking, overly modest, frequently self-effacing writer who read the critics too carefully and was too easily wounded by their sloppily-aimed slings and arrows.

Born in 1887 to Jewish parents in Kalamazoo, Mich., American novelist and playwright Edna Ferber was a hardworking, overly modest, frequently self-effacing writer who read the critics too carefully and was too easily wounded by their sloppily-aimed slings and arrows.

Convinced, for instance, that no one would want to read her novel So Big, she advised her publisher, Doubleday, that it was not worth publishing. Doubleday disagreed — and so did the committee that awarded her the Pulitzer Prize for So Big in 1924.

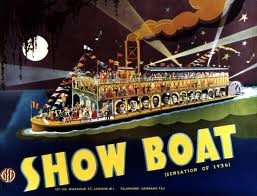

Likewise, Ferber initially thought it preposterous that a musical theatrical production could be based on her 1926 novel Show Boat. In the gay 1920s, musical theatre was lighthearted fare that rarely touched serious social issues. Show Boat, by contrast, dealt compassionately with miscegenation, racial prejudice and wife desertion.

The novel was an instant bestseller, prompting more than a dozen translations as well as radio serializations, stage plays and, in 1927, the masterful musical by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein. But it also prompted an astonishing number of lawsuits that were largely without merit. As the author wrote in her 1939 autobiography A Peculiar Treasure:

“Practically everyone in America — or so it seemed to me — threatened to sue me for something or other they professed to find in the novel Show Boat. River captains I’d never heard of said I had used their boats; descendants of riverside saloon keepers announced that in using their ancestors’ name I had defiled their fair escutcheon and wrecked their political careers; gambling-house owners threatened injunctions; and as a final horror there came a legal messenger from Cardinal Mundelein, of Chicago, saying that the chapter on the Chicago convent school to which Kim Ravenal was sent was an affront to the Church.”

Despite this, Show Boat has become a revered piece of Americana with its own well-deserved niche in U.S. theatrical history. Ferber, who died in 1968, also wrote Cimarron, Saratoga Trunk and Giant — all best-selling novels that were made into motion pictures — and co-wrote two plays, Dinner at Eight and Stage Door, with George S. Kaufman. But it is Show Boat that is arguably her best-remembered work, thanks largely to Kern and Hammerstein.

The last seven decades have seen literally hundreds of productions of the musical around the world. The latest major revival opened at the North York Center for the Performing Arts in October 1993 in a version produced by Garth Drabinsky of The Live Entertainment Co. and directed by Harold Prince. Again, the musical raised the ire of a gang of misguided protestors who, angry and implacable, accused the musical of being racist and — more outrageously –voiced the unprecedented charge that Edna Ferber’s novel, much beloved for 70 years, was nothing more than “hate literature.”

The last seven decades have seen literally hundreds of productions of the musical around the world. The latest major revival opened at the North York Center for the Performing Arts in October 1993 in a version produced by Garth Drabinsky of The Live Entertainment Co. and directed by Harold Prince. Again, the musical raised the ire of a gang of misguided protestors who, angry and implacable, accused the musical of being racist and — more outrageously –voiced the unprecedented charge that Edna Ferber’s novel, much beloved for 70 years, was nothing more than “hate literature.”

The Drabinsky-Prince production of Show Boat went on to win rave reviews and break box-office records. Although it closed in North York on June 11, it is continuing to play to near-capacity houses in New York, where it has won critical acclaim from even the American black press. Earlier this month, it garnered two coveted Tony Awards, for Best Director and Best Revival of A Musical. Ferber would likely have been as agitated by the controversy as she would have been astounded by the musical’s renewed success. She might also have been comforted at the power of large voices to resound down the ages while small voices die out even as their echoes fade. ♦

© 1995