About 60 descendants of Ezekiel Solomons, an 18th-century Jewish fur trader who operated a trading post in what is now Michigan, gathered recently for a first family reunion at Fort Michilimackinac in Mackinaw City, Michigan, about 50 miles south of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

About 60 descendants of Ezekiel Solomons, an 18th-century Jewish fur trader who operated a trading post in what is now Michigan, gathered recently for a first family reunion at Fort Michilimackinac in Mackinaw City, Michigan, about 50 miles south of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Sheldon and Judith Godfrey, a husband-and-wife-team of historians from Toronto, were honoured guests at the two-day event because of the extensive original research on Solomons in their 1995 book, Search Out the Land.

The Godfreys carried the additional distinction of being the only Jews at the reunion. Although Solomons remained loyal to his Jewish faith throughout his life, he married a Roman Catholic, Louise Dubois, and all of their six children were baptized and raised as Catholics.

The event was organized by Thom Smith, a Franciscan friar in Indian River, Mich., who discovered four years ago that Solomons was his fifth-great-grandfather.

Over the last few years Smith has found hundreds of Solomons descendants living in the Great Lakes region of both the United States and Canada. Because many of the six Solomons children had families of 10 to 12 children, he estimates that thousands more remain to be discovered.

“Ezekiel is really an inspiration to us because of his love of faith and his love of family,” he said.

The gathering included a few other Catholic clergy and nuns as well as some people with French Canadian ancestry and members of the Metis, Ojibwa and other aboriginal groups. Descendants of several area lighthouse keepers were also in attendance.

Many came from towns in Michigan, Wisconsin and Ontario, while a few traveled from more distant cities like Toronto, Vancouver and Miami.

“All were very positive about their Jewish ancestry and wanted to know as much as they could about their Jewish heritage,” Sheldon Godfrey said.

“If there’s a point to all this, it is that Solomons considered himself Jewish throughout his life and his family, though all Christian, today value their Jewish roots and would like him remembered that way.”

Family members posit that Solomons was born about 1735 — “that’s just an educated guess,” Smith said — but are no longer certain of his birthplace.

“His great-grandson — in an interview in 1900, when he was about 90 years old — said he was born in Berlin, but I don’t believe this,” Godfrey said. “I believe he was one of the many Bohemian Jews who were expelled by the Empress Maria Theresa about 1746.

“The Jewish refugees of the 18th century came from Bohemia. The people who were wandering around Europe in the middle 1740s were mostly Bohemian Jews.”

Before the Godfreys, few scholars had managed to penetrate very deeply into Ezekiel Solomons’s colourful career. He is regarded as a somewhat elusive historical figure because, unlike other Jewish pioneers of the period, he was illiterate in English and left no papers to posterity.

He was part of a consortium of five Jewish traders that received permission from the British to establish a trading post at Fort Michilimackinac in 1761. Regarded as potentially lucrative but also risky, the venture ended abruptly on June 2, 1763, the date of a native attack on the British stronghold known as the Pontiac uprising. As one of the lucky few to escape with their lives, Solomons was captured and ransomed to British forces in Montreal. All of his trade goods were lost.

He was part of a consortium of five Jewish traders that received permission from the British to establish a trading post at Fort Michilimackinac in 1761. Regarded as potentially lucrative but also risky, the venture ended abruptly on June 2, 1763, the date of a native attack on the British stronghold known as the Pontiac uprising. As one of the lucky few to escape with their lives, Solomons was captured and ransomed to British forces in Montreal. All of his trade goods were lost.

As part of Michigan’s second oldest state park, Fort Michilimackinac has undergone intensive archeological research and thorough restoration, including Solomons’s trading house, which has been faithfully rebuilt. Inside, a wax figure of Solomons stands by his desk in front of a fireplace, surrounded by trade goods and bales of beaver pelts.

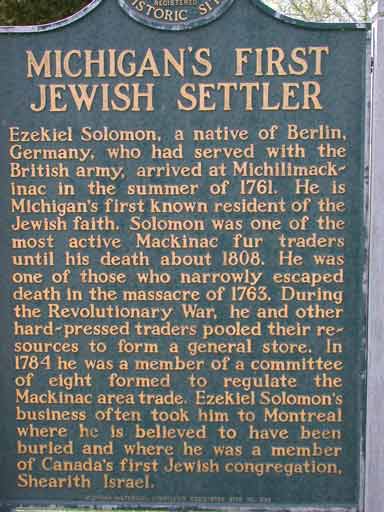

In 1963, with assistance from the Jewish Historical Society of Michigan, the state marked the 200th anniversary of the uprising with a plaque at the entrance to the fort, commemorating Solomons as “Michigan’s First Jewish Settler.” Ever since, costumed historical interpreters re-enact the Pontiac uprising each summer for tourists. During the reunion, many Solomons descendants posed for photographs with a man wearing a fancy dress uniform and three-pointed hat, who has representing their ancestor for the last 21 years.

In the 1770s, Solomons built up a string of successful trading posts north of Lake Superior, prompting rivals in the Hudson’s Bay Company to refer to him in correspondence as “that illiterate Jew.” But according to Godfrey, he was far from illiterate.

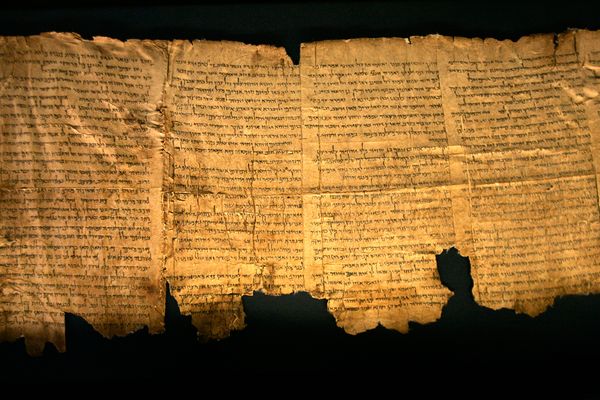

“As a prominent member of the Montreal Hebrew Congregation, he was recorded in its minutes as leading its services and reading in Hebrew,” he said.

Like his fellow fur traders, Solomons often travelled by canoe from the Sault area to attend High Holidays services in Montreal. When his young son Joseph died in 1778, he sought to bury him in the Jewish cemetery there. The congregation consented but inserted a rule into its constitution that uncircumsized males could never be buried there.

In the 1780s Solomons returned with his family to Michilimackinac and lived on Mackinac Island with the other fur traders. Archaeologists have examined the grounds around his family’s living quarters and concluded that he adhered to the laws of kashrut (keeping kosher).

In 1804 he traveled to New York as the Montreal synagogue was then closed. The records of New York’s Shearith Israel Congregation show that he gave charity at the High Holiday services that October and died shortly afterwards without returning home.

Although Solomons is regarded as Michigan’s first Jewish settler, Michigan’s lower peninsula was actually part of Quebec until the War of 1812, said Godfrey, who also claims him as an important Canadian historical figure, albeit one largely neglected by scholars until recently.

Ezekiel Solomons is one of numerous Jewish pioneers between 1740 and 1867 whose exploits are detailed in Search Out the Land. Published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in 1995, the book focuses on “the significant role played by Jews in British North America in the fight for civil and political rights.”

According to Thom Smith, the reunion could not have occurred without the new research contributed by the Godfreys. But there are still many gaps in the genealogical record, he said.

“Ezekiel had a son called Samuel — we call him the mystery son. He traveled to the St. Louis, Missouri area . . . we found records of his children and their marriages but we don’t know what happened after that. That’s a whole other line that needs to be explored.” ♦

© 2003