The first time Sam Gruber stepped inside the Tempel Synagogue in Krakow, Poland, he was “incredibly moved” by what he saw.

The first time Sam Gruber stepped inside the Tempel Synagogue in Krakow, Poland, he was “incredibly moved” by what he saw.

Considered the lone surviving example of the great 19th-century synagogues of Poland, the sumptuously decorated Moorish-Gothic structure had been built as a Reform synagogue in 1862. It had been enlarged in 1892 and again in 1924, and used by the Germans as a stable during World War II. Except for a few occasions, it had been closed to the public since 1945.

An American architectural historian with a passion for Judaic sites, Gruber had seen the Tempel from the outside in 1990 but had not been permitted to enter. Even so, judging only by the elegant but dilapidated facade, he had considered it one of the most impressive buildings in the Krakow-Kazimierz area, a district graced by so many historic buildings that UNESCO has declared it a world heritage site.

When Gruber, Jewish heritage consultant for the New York-based World Monuments Fund, heard in 1991 that the Tempel was to be opened for a gala concert, he rushed back to Krakow to attend. Entering the synagogue, he was awed by the elaborate wall paintings, the curtained ark, the Hebrew inscriptions, the women’s balcony, the perfect symmetry of stone columns and Romanesque arches. All these elements seemed resplendent, albeit badly in need of repair and restoration after so many decades of neglect.

“I was amazed,” he recalls. “The acoustics were wonderful. It was so moving to be in this place which had been closed and locked and empty for so many years. Now to see it suddenly filled with people and springing to life…. I was overwhelmed.”

All told, Gruber has produced an invaluable body of work to date, including extensive surveys of Jewish historical landmarks in six countries, and documenting sites or sparking restorations in nearly two dozen countries.

The next morning, members of Krakow’s small Jewish community asked Gruber whether the WMF might restore the Tempel through its Jewish Heritage Program. As Gruber explained, the WMF has an annual operations grant (it presently receives $100,000 yearly from the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation) but must raise additional funds for its carefully selected restorations. A private not-for-profit organization, the WMF has conserved 180 structures in 68 countries since 1964,and each of these accomplishments had as much to do with raising funds as raising scaffolds.

For two years Gruber searched for funds for the Tempel restoration. Eventually a Houston philanthropist, Joyce Greenberg, gave $30,000 for a new roof in 1994. Greenberg’s gift established a momentum that attracted more substantial funds from the J. Paul Getty Trust, the European Union and others. The restoration is presently about 60 per cent complete and continues on a phased basis, with another $150,000 required for completion.

For two years Gruber searched for funds for the Tempel restoration. Eventually a Houston philanthropist, Joyce Greenberg, gave $30,000 for a new roof in 1994. Greenberg’s gift established a momentum that attracted more substantial funds from the J. Paul Getty Trust, the European Union and others. The restoration is presently about 60 per cent complete and continues on a phased basis, with another $150,000 required for completion.

Invaluable to conservators has been a rare pre-1939 photograph of the Tempel=s interior that surfaced in Warsaw=s Jewish Historical Institute. In November, scaffolding came down in the interior, revealing the breathtaking beauty of the newly-cleaned ceiling. Work is scheduled to begin soon in the apse, behind the lavish ark wall. Beyond its importance to the local Jewish community, the Tempel is expected to provide a fitting prayer setting for the many Jewish groups that stop in Krakow on their visits to Auschwitz and elsewhere.

* * *

Besides the WMF, Gruber is a key player in two related organizations: the privately-funded International Survey of Jewish Monuments (ISJM) and the United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad. All three organizations have participated in thorough surveys of Jewish heritage sites in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Belarus, Ukraine, Turkey, Tunisia, Egypt, India and elsewhere. Gruber credits a variety of geopolitical factors, such as the new ease of travel in former Soviet-bloc countries, for making conditions in the 1990s highly favorable for this type of work.

Since 1990 the WMF has scored many outstanding research accomplishments, often in unlikely locations. Robert Lyon, a New York Times photographer, snapped photos of several synagogues while travelling in Syria in 1995, and later showed the results to Gruber. “I said, ‘This is amazing, no one has ever seen these before,’ and we commissioned him to go back to shoot the other synagogues.” Lyon, who had compiled a wish-list of about 21 Syrian synagogues, managed to photograph 18 of them before he was — as Gruber tells it — kicked out of the country.

In Morocco, a WMF research team visited 80 cities and towns, documenting nearly 300 buildings, cemeteries and mellahs or Jewish quarters. One product of that intensive effort has been an archival-quality set of 600 photographs of Moroccan synagogues that has been deposited in major libraries and institutions in Washington, New York, Jerusalem, Casablanca and other cities. The WMF has also published an abridged report, The Synagogues of Morocco: An Architectural and Preservation Survey, by Joel Zack with photographs by Isaiah Wyner.

Another WMF survey outlines the number and condition of Jewish cemeteries in Poland. The guide has proven invaluable for Jewish genealogists and others planning heritage-related trips to Poland. It’s the kind of project, Gruber says, that would have been almost impossible before the collapse of communism in 1989.

“The openness of the former Soviet Union is revealing amazing collections and monuments that weren’t destroyed,” he says. “And new opportunities have also opened up in North Africa and the Middle East, because it’s now possible to conduct Jewish-related research projects in places like Morocco, Egypt and Tunisia. We’re just beginning to scratch the surface in these places and we’re just amazed to see what is still there: not everything was taken to Israel, not everything was destroyed. There’s never been a better time to be doing this in the last 50 years.”

* * *

With Gruber’s guidance, the WMF has identified thousands of endangered Jewish heritage sites around the world, and published a prioritized list of ten synagogues in immediate need of rescue. Besides the Tempel, WMF restorations have commenced at the Etz Hayim Synagogue in Hania, Crete, and the Paradesi Synagogue in Cochin on India’s exotic Malabar coast.

In determining where to allocate their limited resources, WMF officials generally perform a sort of architectural triage, often choosing a site for restoration (such as the Tempel) from a long list of candidates. Things were different with the Etz Hayim and Paradesi synagogues, however, since each of these buildings is “one of a kind.”

In determining where to allocate their limited resources, WMF officials generally perform a sort of architectural triage, often choosing a site for restoration (such as the Tempel) from a long list of candidates. Things were different with the Etz Hayim and Paradesi synagogues, however, since each of these buildings is “one of a kind.”

Once the center of Crete’s Jewish community, the Etz Hayim Synagogue is the only surviving Jewish monument on the large Greek island. Constructed in the 15th century as a church in a Venetian architectural style, it was converted to Jewish use in the late 17th century. After the Nazis deported the Jews from Crete in 1944, the building was used as a chicken coop, and suffered considerable damage in a 1994 earthquake. Until recently it was an abandoned ruin with a very poor prognosis.

“Overall, the building is in very precarious condition and will probably not survive another ten years without timely intervention,” the WMF declared in 1996. Even though Etz Hayim reflects a “vernacular” or common architectural style, it was an obvious candidate for restoration. About 60 per cent of the work has been accomplished to date.

“I was amazed,” he recalls. “The acoustics were wonderful. It was so moving to be in this place which had been closed and locked and empty for so many years. Now to see it suddenly filled with people and springing to life…. I was overwhelmed.”

The better-known Paradesi Synagogue of Cochin, which still receives worshippers on Shabbat, was erected in 1568 by Sephardic settlers from Europe. It is a square building with a gabled roof, a cupola and a clock tower with numerals in Hebrew, Roman and Malayalam. Inside, one finds white plaster walls, an intricately carved wooden ark, a curved brass bima, a chamber filled with antique lanterns, and hundreds of distinctive blue-and-white willow-patterned Chinese floor tiles dating from the 1700s. In its survey, the WMF described the synagogue as “one of the most beautiful in the world” but warned that numerous repairs were required “before neglect leads to serious damage.” Thanks to the organization’s timely intervention, all but the Paradesi’s picturesque bell tower has been restored.

In Poland, by contrast, endangered Jewish structures are plentiful enough that only a relative few can realistically be rescued. “We can’t save a synagogue in every town in Poland, simply because they didn’t survive,” says Gruber. “But we also can’t do it even in towns where synagogues did survive. It’s too much money and too much work, and there are too few uses for these structures. So we choose buildings that can be effective surrogates for all the ones that don’t get saved.”

When planning a restoration, a fundamental consideration is the desired time period. “Do you want to restore a building to the era when it was built, or to how it looked in a more recent era such as before the Holocaust?” he asks. “This is a decision that every conservator faces, whether it’s a synagogue in Poland or Grand Central Station in New York. With Jewish sites the question is particularly acute, because the shadow of the Holocaust never leaves.”

For Gruber, delicate esthetic questions like these form the pillars of architectural restoration. By preserving key aspects of our architectural past, he says, we preserve essential elements of our culture and history that might otherwise get eroded or bulldozed into oblivion.

“People ask me ‘Why do you care so much about saving old buildings?’ It’s because architecture is a doorway into the past. Sometimes it’s not the building itself that’s so important but having something physical in front of you that forces you to confront another age . . . .

“An old building transports you,” he says. “It’s a time machine. It takes you back into history.”

* * *

Part Two

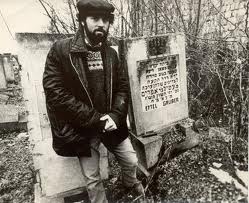

Sam Gruber — Jewish heritage consultant for the World Monuments Fund and other organizations involved in conserving endangered Jewish monuments — lives with his family on a tree-lined residential street in Syracuse, NY, near the university campus. Several blocks from his three-story white clapboard house stands the elegant shuttered mansion that once housed the Jewish War Veterans — a building that Gruber is working with local activists to save. Others include the Onondaga County Poor House and the First Presbyterian Church in East Syracuse. At 42, Gruber is well-known in Syracuse as a force in neighborhood preservation with a self-declared “passionate interest” in preserving heritage buildings of any sort.

Hours by car from any sizeable Jewish community, Gruber’s home is nonetheless the “mission control” for his ambitious goal to catalog and rescue the world’s most important neglected Jewish heritage sites before it is too late. The attic is cluttered with books, files, scrolled architectural drawings, and boxes of materials from the field.

There has been an “explosion” of interest in Jewish heritage, Gruber says, as evidenced by the weighty assortment of recent related titles on his shelves: his favorite is Konin: A Quest, by Theo Richmond. He is also partial to the two important guidebooks written by his sister, author-journalist Ruth Ellen Gruber: Jewish Heritage Travel: A Guide to Central & Eastern Europe (1990) and Upon the Doorposts of Thy House: Jewish Life in East-Central Europe, Yesterday and Today (1994). Stationed in Rome, Ruth is a correspondent for various news media including the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and the New York Times; she is also one of Gruber’s most valued field researchers.

The bookshelves also hold numerous binders with titles like “The Jewish Catacombs, Rome,” “Venice Cemetery Project Notes,” “Czech & Slovak Notes” and “Cochin India.” Maps of Western Russia, the Baltics, and Eastern Europe are pinned to the sloped dormer ceilings, some bearing stickpins as though a military campaign were under way. Masses of paperwork, seemingly layered like geological strata, cover the desks and tables.

Gruber comes by his “passionate interest” in heritage buildings honestly. His father is Jacob Gruber, an anthropologist who founded the anthropology department of Temple University in Philadelphia, where he is still professor emeritus. As a child, Sam often went with him on trips to sites in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. “When I was three years old I was out in the field, doing archaeological work,” he says. “From my father I learned the type of methodical investigation that involves detailed description and careful analysis, which underlies my working method.”

Gruber earned a PhD in architectural history from Columbia University in the mid-1980s, specializing in the Italian medieval period. Part of his studies involved a stint at the American Academy in Rome, where he won the prestigious Rome Prize in art history. He also holds a degree from Princeton. But he admits he knew little then about Jewish architecture. AI had visited every medieval and baroque church in Italy, and I knew Papal history backwards and forwards, but synagogues just didn’t seem terribly relevant.”

In Rome, he met Philipp and Raina Fehl, the founders of the International Survey of Jewish Monuments. In conversation he mentioned that a great-grandfather had founded a synagogue in a small town in Texas and that a grandfather had founded another in southern New Jersey. The Fehls persuaded him to deliver a lecture on the synagogues of rural Texas, then another on the synagogues of South Jersey. More lecture requests followed, each of which required extensive research. Before long Gruber had a growing reputation as an authority on synagogue architecture.

Coincidentally, the WMF had been seeking someone with precisely that rare professional expertise. In 1989, having just completed its first “Jewish” restoration, a synagogue in Venice, the organization was besieged with requests to rescue other Jewish monuments. “Crazy as it sounds, with all the thousands of Jewish organizations in the world, there wasn’t a single one devoted to saving Jewish sites,” Gruber recalls.

The WMF hired Gruber to spend a year compiling a report on the status of Jewish monuments around the world. The task was “impossible,” Gruber admits, and the report still isn’t finished. Gruber also found it next to impossible, back then, to spark any enthusiasm among Jewish audiences for his newly-declared mission. “I’d give a lecture in a synagogue, and there would be a large hostile section of the audience. A lot of the questions would be negative with an accusatory tone. People would say, ‘Why would you want to go to Poland?’ or ‘What is there worth saving,’ or ‘Jews never created any worthwhile buildings or art,’ or ‘Why would you want to do anything there where they destroyed us?”

“I would respond with arguments like ‘There was a thousand years of Jewish history in Poland’ and ‘Clearly not all Poles were hostile to the Jews’ and ‘We have a responsibility to remember our history.’ I made these arguments again and again.”

“I would respond with arguments like ‘There was a thousand years of Jewish history in Poland’ and ‘Clearly not all Poles were hostile to the Jews’ and ‘We have a responsibility to remember our history.’ I made these arguments again and again.”

Jewish institutions also seemed unwilling to recognize the necessity of preserving the material remnants of the Jewish past in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. “Synagogues would say, ‘We can’t save old buildings, we have our leaky roof to fix.’ People weren’t thinking about it in the late 1980s and early 1990s.’

* * *

As part of his work, Gruber forged links with isolated individuals working to preserve particular Jewish monuments in many localities. In 1990 he brought many of them together for The Future of Jewish Monuments, a three-day conference in New York. Delegates from Eastern Europe, the ex-Soviet Union, Israel and America were thrilled to meet colleagues that, in many instances, they hadn’t even known existed. According to Gruber, the conference established a community for the first time and was “a pivotal moment in defining the issues and stating the agenda for the preservation of Jewish monuments around the world.”

Gruber’s job involves much memorable travel. In the mid-1980s he toured Romania with that country’s Chief Rabbi Rosen. He’s also toured Poland with Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka, internationally-recognized authorities on Polish synagogues. And in 1989 he attended, with his wife Judy and sister Ruth, the gala reopening of Budapest’s Szeged Synagogue, the first major restoration of an active synagogue in Eastern Europe. From there the trio set off on an extended road trip through Hungary. “We called ourselves the shul patrol, just for a joke. Wherever we went we’d find the old synagogue. Thus began a process that continued for several years. Ruth got so involved with it that she kept on going. That resulted in her book, Jewish Heritage Travel, then a second one. Now she’s working on a third book.”

In an era in which diaspora Jews are becoming increasingly curious about their roots, Gruber has developed an extensive network of correspondents — mostly American Jews who travel to the Old Country, and report back on the condition of relevant buildings and cemeteries in their ancestral villages. “Thank goodness for e-mail,” says Gruber, who publishes a quarterly newsletter.

“I tell people who are about to photograph a site: ‘You have to pretend you are the last person on earth ever to see this site. If you are a genealogist, don’t just look at the house your family lived in, or the graves of your ancestor only. Look around you: be the eyes for everyone else. Look at things from the point of view of an anthropologist, a folk historian, an economist, a demographer. Try to collect information that will help others understand what you are seeing.”

Commensurate with the rise of interest in Jewish history and heritage, Gruber has noticed a big change in Jewish attitudes towards the WMF’s work with Jewish sites over the past decade. “I don’t get the negative comments any more, now all I get is enthusiasm,” he says. “Today more Jews are travelling, and the moment they go to a place, the first thing they want to see is the synagogue. Now they ask, ‘Why don’t you save this one?’ and ‘How can we help?'”

With every planned synagogue restoration, whether in Poland or India or Greece, Gruber says he asks himself the same question. “What are we bequeathing to the next generation? I always wonder what it’s going to look like in the end. When you visit, will it feel like you’re in a synagogue? Or will it be just another monument on the tourist trail?

“You have to be careful not to lose these buildings. Sometimes you should only do the minimum amount necessary to save them. Sometimes too much care means too much change, and too much change can mean loss of identity.”

All told, Gruber has produced an invaluable body of work to date, including extensive surveys of Jewish historical landmarks in six countries, and documenting sites or sparking restorations in nearly two dozen countries. As he continues to seek funds to rescue endangered sites, he expresses satisfaction that Jewish opinion has warmed towards the project in the past ten years. “I’ve been very impressed by the Jewish community’s ability to grow and change, and open itself to new experiences and new cultural agendas.” ♦

© 2003