Anybody who has had occasion to be on the streets of Toronto about midnight or shortly after must have been struck by the almost sepulchral quiet which then reigns on the streets.

Except the measured footsteps of the policeman as he treads his beat, a sound often audible at a distance of two or three blocks, or an occasional attempt at vocalism from some stray inebriate who is painting the two red by the light of the stars, there is scarcely a sign of human life or human activity throughout the city.

An occasional reporter may pass now and again, generally bound for police headquarters, where he will probably get the last local item that reaches his paper before it goes to press; or a little telegraph boy, carrying in his dilapidated pocket the latest despatches from Hong Kong or Khartoum, may be seen scurrying along the sidewalks, intent on accomplishing his errand and getting home to bed with all the despatch that he can.

But that is all the ordinary midnight observer is likely to see; and unless he makes it his business to inquire more particularly into what amount of business is really transacted under the gas jets, he will find it difficult to believe that over 1,500 men nightly earn their living in Toronto by ways that are usually dark, if not altogether vain.

To attempt to deal sensationally with Toronto’s midnight toilers would be to write down the writer an ass. With the exception of a few chronic drunkards and criminals, there is no class in this city whose conduct during such hours is such as to furnish even the most enterprising reporter with a single lurid item.

A man cannot write a dime novel in which the heroes are merely telegraph operators, or journalists, or bakers, or policemen, and when incessant pen-scratching or dreary, endless marches on the sidewalk have to do duty for incident. But though Toronto’s midnight “sensations” are wholly imaginary, there is yet enough of interest attaching to the various industries in full blast at that hour to warrant some description of the workers and the nature of their labor.

A man cannot write a dime novel in which the heroes are merely telegraph operators, or journalists, or bakers, or policemen, and when incessant pen-scratching or dreary, endless marches on the sidewalk have to do duty for incident. But though Toronto’s midnight “sensations” are wholly imaginary, there is yet enough of interest attaching to the various industries in full blast at that hour to warrant some description of the workers and the nature of their labor.

As you pass the corner of Wellington and Scott streets at almost any hour from midnight to daybreak, you may notice a bright light in the third story windows of the G. N. W. telegraph company’s building. That is the operator’s room. Were you to enter it by day you could scarcely hear your own voice over the perpetual click, click which arises on every side of you.

At night time things are not so noisy, for the staff is diminished by considerably more than one half. On ordinary nights, when nothing special is expected in the press despatches, a corps of a dozen men or so is sufficient. But if news is expected regarding some important battle or some great disaster, this force is considerably augmented.

Last night, for instance, when long despatches were expected regarding the lost State of Florida, three or four members of the day staff were put into requisition. As a rule eight or nine men are sufficient to cope with the press despatches, the others being engaged in despatching and receiving half-rate messages, which are liable to drop in all through the night.

The staff commence work at 6 p.m. and are on continuous duty until 2 a.m. or later. Night operators receive the same pay as those working through the day, but it is calculated that they work at least an hour less. Thirty words a minute is considered a good average for an operator, which is about equal to one column of the Globe per hour.

The despatches are written out on what is technically known as “flimsy,” a very light hard paper. From one to ten sheets of flimsy, according to the lateness of the hour or the importance of the messages, are thrust into the envelope by the receiving clerk and shot down a tube into the ground floor, where boys are always in waiting to convey them to the various newspaper offices. Altogether, the night staff employed at this office numbers from 25 to 30 men and boys.

From the telegraph to the newspaper office is but a short step. There are probably about 130 hands employed around the Globe building at night, and nearly the same number on the Mail. The other morning newspapers have between them a total staff of about 120 hands, making an aggregate of nearly 500 men and boys employed on local daily journals. Of this number about 120 are compositors; the rest includes editors, reporters, proofreaders, stereotypers, engravers, pressmen, route boys and wagon drivers. The time for going to press varies, the latest hour fixed being about 4 o’clock.

From the telegraph to the newspaper office is but a short step. There are probably about 130 hands employed around the Globe building at night, and nearly the same number on the Mail. The other morning newspapers have between them a total staff of about 120 hands, making an aggregate of nearly 500 men and boys employed on local daily journals. Of this number about 120 are compositors; the rest includes editors, reporters, proofreaders, stereotypers, engravers, pressmen, route boys and wagon drivers. The time for going to press varies, the latest hour fixed being about 4 o’clock.

From food for the mind to food for the body is a natural enough transition. Although all those employed in night-work on a morning journal are supposed to work hard, and although the nature of their labor is naturally trying to the strongest constitution, it is not strictly speaking, a physical task. It tells rather on the nerves than on the muscles.

People who take up the morning paper, clean and crisp as it lies on their breakfast table, would find it difficult to realize how much varied labor and thought had gone to make up the trim columns they see before them, and which look as orderly and symmetrical as if every word had been evolved and set in position by means of machinery.

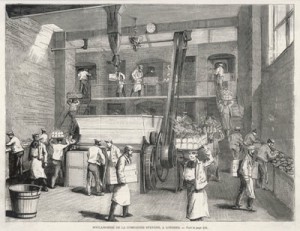

Yet the newspaper is not the only article on the breakfast table which is the product of long labor through sleepless nights. That crisp new loaf, which yields so coyly to the knife, is another result of toil by night. For in this city there are over three hundred journeymen bakers, most of whom repair to their work at an hour when the ordinary citizen is slumbering peacefully beneath his blankets.

Years ago, Toronto bakers had a much harder time of it than now; when their custom was to enter the bake-house at 9 o’clock of an evening, and not quit until 2 or 3 in the afternoon. A few winks on a pile of old flour sacks sufficed them for sleep; and what little they ate was invariably taken at the scene of their work. Under such conditions, it is little wonder that the business soon got the reputation of being an unhealthy one.

Years ago, Toronto bakers had a much harder time of it than now; when their custom was to enter the bake-house at 9 o’clock of an evening, and not quit until 2 or 3 in the afternoon. A few winks on a pile of old flour sacks sufficed them for sleep; and what little they ate was invariably taken at the scene of their work. Under such conditions, it is little wonder that the business soon got the reputation of being an unhealthy one.

Now, however, all this is changed. The men, as a rule, do not go to work before 3 or 4 a.m., and are not in the bake-house for over eleven hours at a stretch. Still, the wear and tear on the physical system is very great, owing to the immense amount of muscular exertion required in the process of bread-making. According to a prominent baker of this city, an average hand in the business actually lifts in the course of his work three or four tons of dough. Toronto today presents more advantages to the class of workmen than any other city on the continent. Wages run on an average from $12 to $8 a week, and are at present about $3 ahead of those paid in Canada’s stingy little capital. ♦

◊ This is No. 1 in a series of articles from the Toronto World newspaper on “Toilers of the Night” — professionals who worked by gas jets in the Toronto of 1884. See also Toilers of the Night: a Toronto bakery and hospital (1884)