From Growing Up Jewish: Canadians tell their own stories (1997)

From Growing Up Jewish: Canadians tell their own stories (1997)

My earlier recollection goesback to the very early 1920s, sitting on the stoop of our dry-goods store on Spadina Avenue and Baldwin Street (southeast corner), watching the Sunday evening church parade go by. These were the strollers emerging from two nearby Christian churches, the Western Congregational Church, just to the south, and the Christadelphian Church on Cecil Street, just to the north. Within a year the scene had radically changed: the two churches had been transformed into synagogues — totally Judaicized — the former becoming the Londoner Shul (officially the Men of England), and the latter becoming the Ostrovtzer Shul. The change was symptomatic of two trends: the demographic move of the indigenous Anglo-Saxons out of the Spadina Avenue area, and the trend to Church union, which reduced the number of Protestant conventicles and effectively removed from the Canadian scene such historic names as Congregationalist, Wesleyan and Methodist.

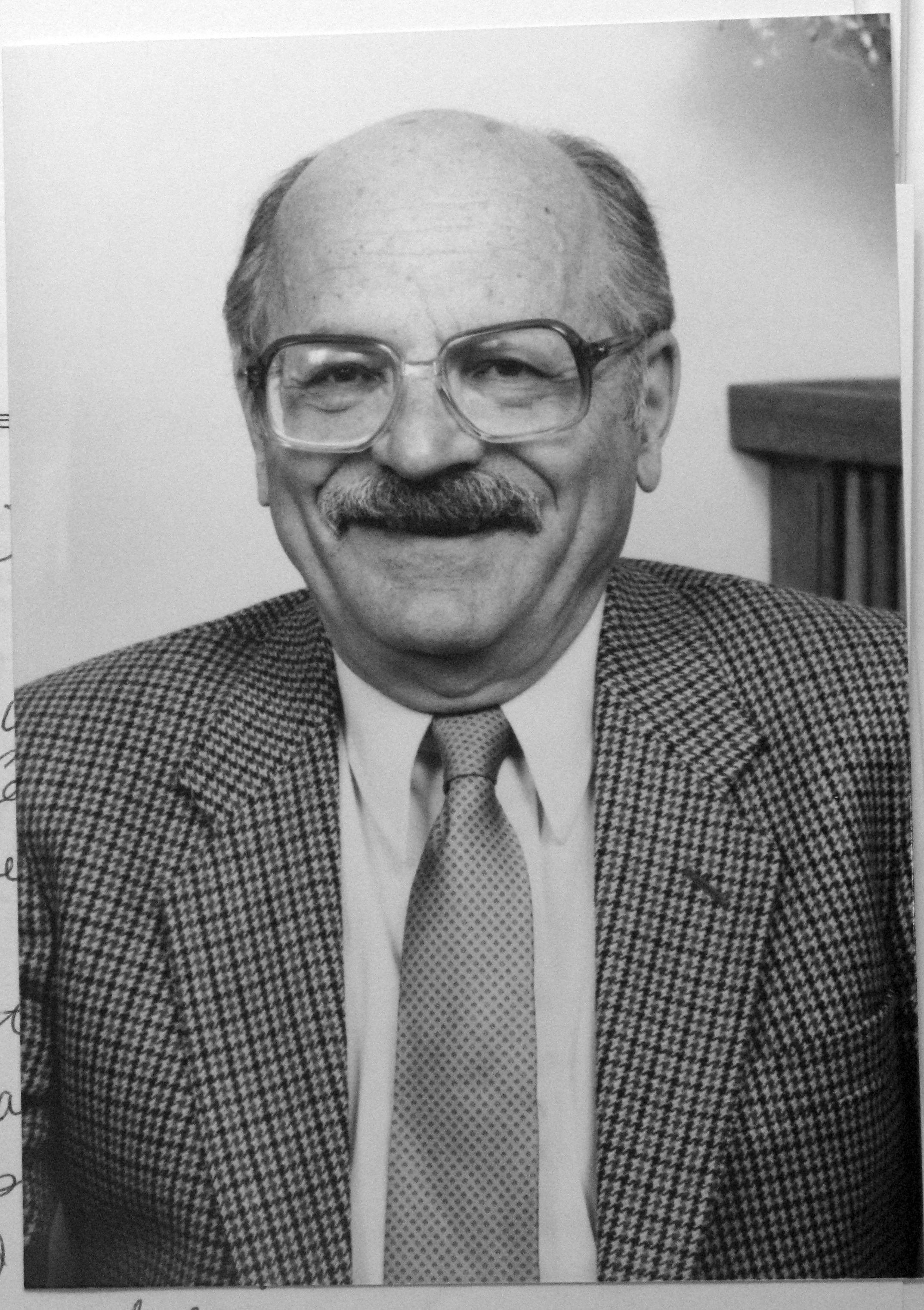

Forty years later, when I was employed by the Canadian Jewish Congress, that same dry-goods store was the editorial office of the Vochenblatt, a pro-Communist organ of the Left, edited by the late Joshua Gershman. Mr. Gershman maintained a love-hate relationship with me, denouncing me in his paper one week, then beckoning me into his den to present me with the gift of a book of memoirs by a Yiddish stalwart. His backhanded way of paying a compliment once led him to compare me with another of his targets, fur worker unionist Max Federman. After listing the misdeeds of Federman, the lackey of the capitalist class, he wrote, “But there is one who is even lower than Federman!” And that villainous person was none other than Ben Kayfetz!

Why the dry-goods store? In the year 1918, my father was stricken with a progressive ailment that removed his motor ability, and my mother looked to the store and other livelihoods to care for her family of five children. The two words “dry goods” are to be pronounced drhygulz, with a guttural r, as it was not until many years later that I learned that this was something other than an accepted Yiddish name for a retail business that dealt in children’s clothing.

Within a year we had moved away from Spadina to 893 Dundas Street West, in the Claremont-Bellwoods area, where the house was provided with a storefront that served over the years as a grocery, barbershop, bakery, and finally poultry shop. Some of these enterprises were operated by our family, others by lessees or tenants. Between 1926 and 1929, we leased the property to a barber (who, like many Jewish barbers, doubled as a klezmer), and we dwelt at other addresses, never very far away. This area lacked the glamour and colour of Kensington (where we lived briefly in 1926) and had no neighbourhood name to attract interviews by newspaper reporters. It was on the edge of Italian territory — which then consisted of three lone thoroughfares, Manning Avenue, Claremont, and Bellwoods, extending between College and Dundas streets — infinitely smaller than after the massive Italian influx that came after World War II.

We had a rich variety of experiences growing up in this reputedly drab part of Toronto. I recall the excitement of watching herds of cattle being driven down Claremont Street — not on trucks, but on foot — with yapping dogs running alongside! This was not a one-time only procedure; I remember it happening several times. The incongruity of cattle treading on a paved road in a built-up urban area never occurred to us children. Years later, when I mentioned this in company, I was greeted by total disbelief — so much so that to escape embarrassment I gave up telling the story. But then I found confirmation in the memory of Johnny Lombardo, of Radio CHIN, who is approximately my age and was raised in the same neighbourhood. The only difference is that, in his recollection, the cattle were moving northward. (This is unlikely, because they were probably being driven south to the abattoir at the foot of Tecumseh Street, having started their “walk” at the Junction stockyards.)

I remember one thing from our brief stay in Kensington in 1926. There was a group of boys who had a ongoing handball game on Baldwin Street every weekday. But on Saturday, no game! Under traffic conditions today, such a sport would be unthinkable, but in 1926 it was possible; Sabbath observance reigned supreme. All shops were Jewish and all were shut down. The main shopping day was Thursday in preparation for the Sabbath that came the following Friday evening.

Who were our neighbours on Dundas Street? There was Mr. Baker, the damski shneider (ladies’ tailor), whose neighbour the cobbler read him the Yiddish daily newspaper. In the tradition of heymishe shneiders, he was Jewishly illiterate. Then there was Richman, the shuster, who carried on in turn in three stores all within one block and whose billboard proclaimed he had cobbled shoes in all the capitals of Europe! The modest, learned parents of Dr. Ben Cohen, staunch General Zionists, lived in the neighbourhood. Another family were shnapps dealers, the polite word for bootleggers. They moved, appropriately, to Chicago, but when they moved back to Toronto three years later they had graduated to South Parkdale.

I made mention of the Londoner Shul, which boasted an imperial connection. But the members were hardly true-blue, hearts-of-oak Englishmen as one might think from the name. My Uncle Paysha was a member, and goodness knows there was little that was English about him. Whence the Anglophile title? It dawned on me years later. It was the practice at the turn of the century for immigrant ships to stop at an English port such as Liverpool for quarantine purposes. The stay lasted about two weeks, just long enough for the Litvak immigrants to acquire a taste of tweed tailoring, a pipe, and the other paraphernalia of civilized British living. And they proposed to continue this pretense as a touch of Old England. Years later they made an unsuccessful attempt to affiliate with the Board of Deputies of British Jews in Britain.

Another shul — much humbler in its structure, occupying a shtiebl on lower Huron Street — bore the pretentious, “big-city” name of the Anshe New York. Most landsmanshaftn were named for Eastern European shtetlekh or provinces. But New York? hardly a name to conjure up shtetl memories! Years later I found the answer. These were a group of needle workers who worked together and prayed together. Dependent on the seasonal supply of work in Toronto and New York, they moved from one location to the other when the season changed. But in the mid-1920s, the United States lowered the boom on immigration. There was no longer an open border, and the group found themselves confined to Canada’s soil. So they remained in Toronto, stayed in the needle trade, and continued worshipping together as Anshe New York in memory of the “open border”!

Nineteen twenty-seven marked the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolutions. I use the plural, for as we know there were two: the February and the October. I, like the Revolution, was ten years old. My mother, I’m sure, was unaware of the distinction between the two political upheavals. She knew there had been a revolution which was long desired by the oppressed people of Russia (she had left in 1907), and in a vague way she favoured anything that removed the hated hand of Tsarism and pogroms. She still recalled with favour words like “democracy” and “Duma.” Which is why I found myself seated with her at a public meeting in the Ukrainian Labour Temple on Bathurst Street (opposite Alexandra Park). There were lengthy speeches in Ukrainian, of which I understood not a word. What I do recall is a speech in English, heavily accented by the Glaswegian dialect thereof, by a top Communist party official named Jock MacDonald, who had praise and homage for the Bolshevik Revolution. What marred his speech, however, were the gales of laughter from the audience hearing his praise for the Rooshan Revolution and his panegyric for Soviet Roosha. And within a year this Scottish proletarian was in disgrace, no longer secretary general of the party. He had made the wrong choice politically, having opted for the Trotskyist faction. This was my first lesson in dialectical materialism and the impermanence of political correctness.

My first experience in a mushroom synagogue was early in the 1920s, when I attended such a service in the Templars Hall on Queen Street West, just beside the 999 Queen Street Insane Asylum as we so insensitively called it. An uncle of ours had a hardware business on Queen Street West (which duly failed). With other Jewish shopkeepers they hired the Templars Hall for the High Holidays. I was seated in the gods, perched near the ceiling, and had no good coign of vantage to watch the proceedings. But what I did see was the blessing of the kohanim (priests), a procedure which gave me an eerie, fearful feeling. The figures, totally enveloped in talaysim (prayer shawls) from head to toe, arms outstretched but completely cloaked, rocking back and forth like automatons to the rhythm of the murmured blessing, resembled huge machines. It came as no surprise to be told that if one looked at them one risked being struck blind!

There was a Mr. Bloom (grandfather of poet Phyllis Gottlieb) — whose fur shop was in the same Queen Street-Dovercourt Road area — for whom mother did “finishing work” at home. A venerable, patriarchal figure (though he was clean shaven), his appearance and age demanded respect and deference. Occasionally he would telephone our home about my mother’s fur work, and when my sister answered she spoke in her less-than-perfect Yiddish, as that was how one addressed elderly Jews. He would reply in flawless, unaccented English. But my sister still addressed him in Yiddish; she knew of no other way of addressing the elderly, even if they were clean shaven.

At one point in the mid-1920s, my mother answered an advertisement in the Yiddish daily looking for a cook general on a Jewish-owned farm near Georgetown. It wasn’t clear to her whether this was to be a summer resort, a favourite sideline for Jewish farmers (witness the Catskills). For some reason she took me along for the ride. I was all of nine. We travelled on the old Toronto-Guelph radial line (long since defunct), and I recall passing such exotic-sounding stations as Eldorado Park, and some less exotic names as Streetsville, Cooksville, Erindale. I was not present at the interview, but remember sitting alone in the radial car station awaiting my mother’s return. My mother did not accept the job. We returned home and I forgot the episode. More than thirty years later I received a telephone call at the office of

the Canadian Jewish Congress from a Mr. Morris Saxe and was asked to come to his daughter’s home, where he had some documents to leave with the Congress. I found him in bed (he died within the year), and he proceeded to tell me of his abortive attempt in the 1920s to train and settle on the land up to seventy-five Jewish children living in a orphanage in Mezritch in Eastern Poland. This idealistic plan failed, sabotaged, he said, by politicians and others who had their own agenda. He wanted the documents to be left with a communal agency like the Congress as it was a piece of history that ought to be preserved. (In one respect, the project was a success, saving the seventy-five from Hitler’s killers some fifteen years later.)

I spent several hours with Mr. Saxe and accepted the documents. On the way home it occurred to me that Morris Saxe was the prospective employer — the Georgetown dairy farmer — who had interviewed my mother back in the 1920s! Now I recalled what he said about his wife, who in the end had to take on the mammoth task of cooking for and feeding the youngsters — a job which Mr. Saxe said was responsible for her premature death. It was this punishing task that my mother had happily avoided.

More recently Mr. Saxe’s grandson, David Fleishman, has made a film entitled A Man of Conscience about this almost-forgotten episode in Ontario Jewish history, an episode in which I unwittingly had a very minor role. ♦

Reprinted from Growing Up Jewish: Canadians Tell Their Own Stories (McClelland & Stewart, 1997). Reprinted courtesy of the Kayfetz family. © 2012 by the family of the late Benjamin Kayfetz.