Humanity’s future: will it be “earthbound” or “spacebound”?

Humanity’s future: will it be “earthbound” or “spacebound”?

My uncle, the artist Gerald Gladstone, posed this question to me recently outside Yorkdale shopping centre in North York. We were standing in the parking lot near The Bay, beside one of his major works, a bronze colossus called Universal Man, which was installed there in late September. He seemed pleased that people were stopping to look at the sculpture and read the plaque; some were even sitting on the pedestrian-friendly platform.

Universal Man stands more than 21 feet high and weighs some 6,000 pounds; it is hard not to notice. Its feet, in a manner of speaking, are made of clay; its legs are thick and rolling, like mountains; the organic lines of a prototypical Canadian landscape may be detected in its midriff; and the billowing imagery of clouds is visible in its upper body. The figure’s arm is outstretched to heaven; in its hand is a sphere. According to its creator, Universal Man symbolizes “earthbound human energies reaching towards a higher universal knowledge.”

Despite its considerable girth (and its considerable worth, now estimated at more than $1 million), Universal Man was summarily toppled from its previous location beside the CN Tower, where it had stood since 1976, when construction began on SkyDome in 1987. The piece, Gladstone notes, “already has a history.”

Born into a working-class family in Toronto in 1929, Gladstone began painting at age 15. One of a group of eminent artists that emerged here in the 1950s (others included Harold Town and Michael Snow), he had a successful one-man show in New York in 1963 and returned home a recognized fine artist. His public works since then have included the Three Graces sculpture and fountain at Bay and Wellesley, Toronto; the McGillivray fountain at the CNE, Toronto; a sculpture and fountain for Place Ville Marie, Montreal; the Martin Luther King Memorial in California; and many other works across Canada and internationally.

Like the Universal Man, Gladstone’s feet seem firmly planted on the ground, his head in the clouds. This came across very well when I asked him to tell me more about the sculpture that stood before us so dramatically against the afternoon sky. Instead of a down-to-earth physical description involving design, form and matter, he responded with some lofty ideas on the future of civilization.

“I don’t know whether our species is about to face an imminent set of decisions,” he said. “Are we going to relate to the planet in future, or are we going to relate to a space environment? Will we abandon the planet as a viable nest, even though it is a spaceship of the highest calibre and contains answers to all the best questions we can ask?”

“I don’t know whether our species is about to face an imminent set of decisions,” he said. “Are we going to relate to the planet in future, or are we going to relate to a space environment? Will we abandon the planet as a viable nest, even though it is a spaceship of the highest calibre and contains answers to all the best questions we can ask?”

This dichotomy — earthbound and spacebound — is an important key to Gladstone’s art. His “earthbound” pieces feature the organic, sensuous curves of earth: women, men, landscapes, skyscapes. In these works, one can see the influence of his friend and mentor, the late British sculptor Henry Moore.

Alternately, his “spacebound” pieces offer random slices of the perfect geometry of the universe: straight lines, cones, spheres, parabolic curves, nuclear configurations, intricate abstract spatial interrelationships. In these works, one sees affinities to the art of the late Buckminster Fuller, another friend and influence of Gladstone’s. The artist says he has also been shaped by a school of abstract expressionists that emerged in New York after 1945, whose ranks include Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning.

In his earlier days, Gladstone worked at the same engraving house where several painters of the Group of Seven were apprenticed. Like them, he is aware of the overriding importance of the landscape as a tradition in Canadian art.

“Canadian artists are plagued and blessed with this tradition,” he said. “It gives them a safe launching pad for their ideas but it can also trap them into not experimenting with newer forms.” He said that he has distilled the organic curves and lines of the landscape for use in other forms, such as Universal Man.

Art, according to Gladstone, is an essential part of the process of how humankind gains knowledge. Even the primitive cave painters, he said, were doing far more than just beautifying their homes. Rather, they were attempting to gain mastery over the wild and ferocious animals whose images they captured so well in muddy ochre on their walls. Our discussion served as an important reminder to me that good art is more than society’s window-dressing, more than mere decoration. It may be rooted in the soil, but it reaches for the stars. ♦

Originally appeared in the Canadian Jewish News. © 1998

* * *

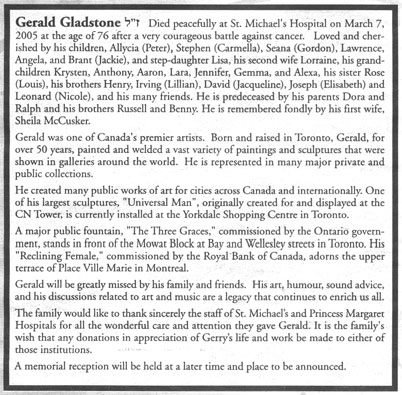

GERALD GLADSTONE (1929-2005)

Gerald Gladstone, the prominent Canadian sculptor who died in Toronto on March 7 at the age of 76, left behind a legacy of public works in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver and other cities across Canada as well as notable pieces in public and private collections around the world.

Gerald Gladstone, the prominent Canadian sculptor who died in Toronto on March 7 at the age of 76, left behind a legacy of public works in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver and other cities across Canada as well as notable pieces in public and private collections around the world.

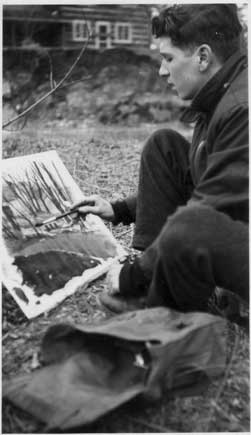

Born on Jan. 7, 1929, Gladstone grew up as the sixth of nine children in a working-class family in a Jewish neighbourhood in Toronto. He began painting at age 15 and worked in his early days at an engraving house where several painters of the Group of Seven had apprenticed.

Part of a group of eminent Canadian artists to emerge in the 1950s, he was the art director of a leading Toronto advertising agency until he won a Canada Council travel grant in 1959. Relocating his young family to London for several years, he studied at the Royal College of Art and met British sculptor Henry Moore, who became a significant mentor. He established his reputation with two successive exhibitions in New York and London in the early ’60s.

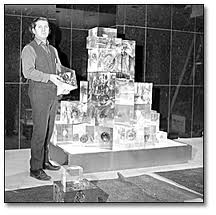

With their intricate intersecting series of geometric cones, parabolas and rods, his welded metallic sculptures seemed to convey some cosmic truths on both the galactic and microscopic levels, and brought him a rush of acclaim and international commissions throughout the ’60s and ’70s.

Uki, a firebreathing dragon that rose up from a manmade lake, was one of three major commissions completed for Expo ’67, the Canadian-hosted world’s fair. His international work included a memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr. in Los Angeles and a public fountain in Canberra, Australia. Even at the height of his career, he always completed his complex assignments on time and always at or under budget.

Uki, a firebreathing dragon that rose up from a manmade lake, was one of three major commissions completed for Expo ’67, the Canadian-hosted world’s fair. His international work included a memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr. in Los Angeles and a public fountain in Canberra, Australia. Even at the height of his career, he always completed his complex assignments on time and always at or under budget.

Besides his welding skills, he mastered the technological art of encasing smaller sculptural pieces in blocks of clear lucite. And in addition to the heavenly geometric forms with which he experimented, he also sculpted and painted more rounded figures reflecting the sensuousness of earthly forms and landscapes.

Although he received some lucrative commissions, Gladstone had to foot the cost of supplies and often faced a challenge in supporting his wife and six children. Once, in London, he found a resourceful way to keep on working after his money ran out. “I had a studio at the Royal College of Art, but nothing to work with,” he explained. “I watched some guys near King’s Cross welding fire-escapes and I wondered what they’d do with the scrap. I asked them to give it to me — and they did.”

Another London incident involved Moore, who agreed to critique Gladstone’s exhibition at a city gallery provided he did not have to encounter any art dealers. “I instantly agreed although I had no idea how I could exclude the gallery owners,” Gladstone explained. When Moore arrived, the young artist audaciously summoned the gallery owners into their glass-enclosed office. “I know you are going to hate me, but I must do this,” he apologized as he locked them in; he then closed the gallery for 90 minutes so that his time with Moore would not be interrupted. “We could see the gallery owners in the office, and they smiled and acknowledged the presence of the great master in their gallery,” he recalled.

Another London incident involved Moore, who agreed to critique Gladstone’s exhibition at a city gallery provided he did not have to encounter any art dealers. “I instantly agreed although I had no idea how I could exclude the gallery owners,” Gladstone explained. When Moore arrived, the young artist audaciously summoned the gallery owners into their glass-enclosed office. “I know you are going to hate me, but I must do this,” he apologized as he locked them in; he then closed the gallery for 90 minutes so that his time with Moore would not be interrupted. “We could see the gallery owners in the office, and they smiled and acknowledged the presence of the great master in their gallery,” he recalled.

Two years ago the Art Gallery of Ontario mounted a small retrospective of Gladstone’s work in a hall adjacent to its large Moore collection. Although Gladstone’s career went into eclipse in his later years, he never stopped working. He finished his last commission, a memorial for a slain policeman, only months before he died of cancer.

He was the son of British-born parents: Ralph and Dora (nee Alexander) Gladstone were born in East London and Bristol respectively. Originally from Poland, the family anglicized its surname from Glicenstein to Glickstein in England, and to Gladstone in Canada.

He was the son of British-born parents: Ralph and Dora (nee Alexander) Gladstone were born in East London and Bristol respectively. Originally from Poland, the family anglicized its surname from Glicenstein to Glickstein in England, and to Gladstone in Canada.

Gerald Gladstone leaves his children Allycia, Stephen, Seana, Lawrence, Angela and Brant, his second wife Lorraine, his sister Rose and brothers Henry, Irving, David, Joseph and Leonard. He is predeceased by his parents and brothers Russell and Benny. ♦

The writer is Gerald Gladstone’s nephew.

Originally appeared in the London Jewish Chronicle. © 2005

You may also wish to read a A Remembrance on Remembrance Day about my father Russell.

3 comments for “A sketch of artist Gerald Gladstone”