Boasting numerous gems of Georgian architecture, this hilly, former spa town, set in the Peak District of the English Midlands, has been recognized since Roman times for its warm mineral springs — as musicians who venture into the orchestra pit of the Buxton Opera House know only too well.

Boasting numerous gems of Georgian architecture, this hilly, former spa town, set in the Peak District of the English Midlands, has been recognized since Roman times for its warm mineral springs — as musicians who venture into the orchestra pit of the Buxton Opera House know only too well.

Alec Guiness, Laurence Olivier, Anna Pavlova and many other famous players once trod the boards of this neo-baroque theatre between its rise in 1903 and its sorry devolution into a lowly cinema in the depressed 1930s. Blacked out for decades, the original gilt, cream and blue tones of this original Thomas Matcham theatre were restored in 1979, along with the cherubs above the stage and the ten painted Muses that grace the domed ceiling.

Judith Christian, who has risen from usherette to manager in her 17 years here, makes no bones about admitting that a ghost inhabits the Buxton Opera House or that a river (of sorts) runs through it. As if from a broken pipe, a rivulet of Buxton’s famous water continuously trickles across the cement floor of the orchestra pit.

Visitors stream here in summer for two high-profile theatrical events, the Buxton Opera Festival and an international Gilbert & Sullivan Festival. Summer is a time of almost full occupancy for stylish local inns like the Elizabethan-era Old Hall (whose most famous guest was Mary Queen of Scots), the Georgian-era Lee Wood Hotel and the Victorian-era Palace Hotel.

The Gilbert & Sullivan Festival attracts G&S aficionados from some 16 countries, including more than 50 from Canada, says Ian and Neil Smith of Halifax, England, the father-and-son team who started the event three years ago. Amateur companies perform most of Gilbert and Sullivan’s 13 comic operas during the festival; prizes are awarded for the best productions. This year’s festival runs Aug. 4 to 18 (1998) in Buxton after nine days of earlier related activities in Philadelphia, Pa.

The Gilbert & Sullivan Festival attracts G&S aficionados from some 16 countries, including more than 50 from Canada, says Ian and Neil Smith of Halifax, England, the father-and-son team who started the event three years ago. Amateur companies perform most of Gilbert and Sullivan’s 13 comic operas during the festival; prizes are awarded for the best productions. This year’s festival runs Aug. 4 to 18 (1998) in Buxton after nine days of earlier related activities in Philadelphia, Pa.

“It’s one of the best fortnights of the year, and the atmosphere in Buxton is electric when it’s on,” says Christian. “You’ve just got to be here to believe it.”

Situated about 1,000 feet above sea level, Buxton is the highest market town in England. It is encircled by the green, 542-sq-mi. Peak District, Britain’s first national park. Although the town is ringed at a greater distance by the industrial cities of Leeds, Sheffield and Manchester, fresh breezes from the Derbyshire hills have kept it clean.

In a former age, Buxton’s healing waters made it England’s second most popular spa town after Bath. Mary, Queen of Scots first took the waters here 1573, and wrote that “the cure hath successfully dried my body of the phlegmatic humours” that had plagued her.

In later centuries scores of visitors abandoned the crutches that had brought them here after soaking in the Buxton water, which flows from the ground at an unvarying temperature of 82 degrees F. While the thermal baths are no longer in vogue, residents still make pilgrimages to a fountain in a town square to fill plastic jugs with water for home consumption. Buxton water is also commercially bottled in sparkling and plain varieties, and available in hotels and shops.

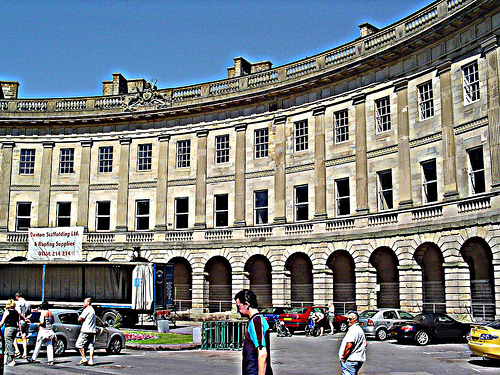

There is an architectural opulence here that is surprising for a town of some 23,000 inhabitants. The town’s most emblematic building, The Crescent, was built in Georgian times when Buxton was home to only 800 persons. Now being restored, this elegant semi-circle of classical arches and pilasters was once the most fashionable address for those taking the aquatic cure.

Nearby is the Cavendish Arcade, a shopping mall strong on antiques, clothes and crafts. Its ceramically-tiled turquoise walls and aquatic decorative touches are unmistakeable clues to its past life: it arose in 1852 as a thermal bath house. Another distinctive structure, the Devonshire Royal Hospital, was originally a stables and sheltered exercise ground for horses. In 1878 it was covered with a domed roof that, at 150 feet across, made it briefly the largest domed structure in Europe.

Yet another monument indicative of a past civic wealth, the Pavilion Gardens is a landscaped promenade erected in 1871 so that Victorian strollers could respectably take the air. Like the rest of Buxton’s architectural opulence, it reflects the considerable largesse of Buxton’s historic patron, the Duke of Devonshire.

A short drive from Buxton brings one to Chatsworth Hall, the historic home of the fabulously wealthy Dukes of Devonshire; the 11th Duke and his family are now in residence. Put simply, Chatsworth Hall is nothing less than England’s answer to Versailles.

A short drive from Buxton brings one to Chatsworth Hall, the historic home of the fabulously wealthy Dukes of Devonshire; the 11th Duke and his family are now in residence. Put simply, Chatsworth Hall is nothing less than England’s answer to Versailles.

Upon approach, one sees an enormous cream-colored grand hall floating on a panoramic sward on which sheep and even deer tamely graze. The richly-furnished interior is a sort of live-in fine art museum featuring, for example, a Breughel in the China Closet, a Tintoretto on the West Stairs, a Rembrandt in the Sculpture Gallery. (Chatsworth is open every day for tours from Mar. 20 to Nov. 3.)

While in the region, visitors may wish to visit one or more local caverns; guided tours offer a glimpse into a weird subterranean world where stalagtites and stalagmites have been growing undisturbed for millenia. They may also wish to visit the prehistoric monument at Arbor Low, a smaller version of the famous Stonehenge, whose fallen stone slabs lay sleeping in a clockface arrangement.

Buxton is about a 45-minute ride by car or train from Manchester. British Airways offers Super Shuttle flights between Manchester and London’s Heathrow airports on approximately an hourly basis. ♦

© 1998