Cecil B. DeMille and the Golden Calf, a 508-page hardcover biography by Simon Louvish (Faber & Faber, 2008) covers the life and career of the legendary American film director from his birth in 1881 to his death in 1958, two years after he completed his last and most famous film, The Ten Commandments.

Cecil B. DeMille and the Golden Calf, a 508-page hardcover biography by Simon Louvish (Faber & Faber, 2008) covers the life and career of the legendary American film director from his birth in 1881 to his death in 1958, two years after he completed his last and most famous film, The Ten Commandments.

DeMille always expressed a deep attachment for the Bible, both the Old and New Testaments, as he referred to them. He was raised a Protestant but Louvish reveals that his father was Protestant and his mother Jewish.

Of the 70 motion pictures that he directed, 52 were silent and many of the best are unknown to modern audiences, according to Louvish, who has also penned books on W. C. Fields, the Marx brothers, Laurel and Hardy, Mack Sennett and Mae West.

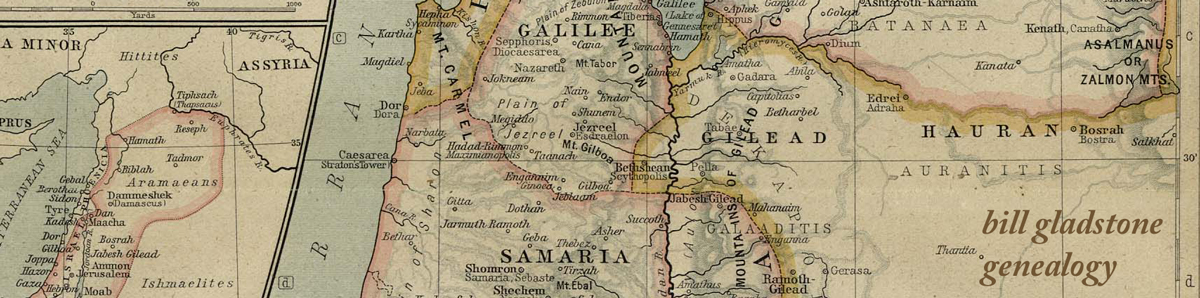

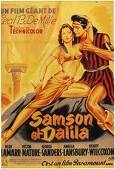

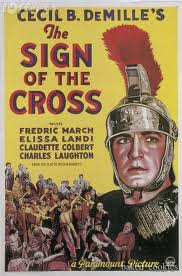

DeMille’s first historical epic was Joan The Woman (1917), a telling of the Joan of Arc story. He cemented his reputation as a master of the grandiose Biblical saga with a silent version of The Ten Commandments in 1923. He made King of Kings, a film about the life of Jesus, in 1927, and Samson and Delilah in 1949.

DeMille was in his early 70s when he began work on the modern version of The Ten Commandments, which famously featured Charlton Heston as Moses and Yul Brynner as Pharoah. Memorable performances were also delivered by Anne Baxter, Yvonne de Carlo, Cedric Hardwicke, John Carradine, Vincent Price and Edward G. Robinson. As well, the production featured 30,000 extras and 15,000 animals.

DeMille was in his early 70s when he began work on the modern version of The Ten Commandments, which famously featured Charlton Heston as Moses and Yul Brynner as Pharoah. Memorable performances were also delivered by Anne Baxter, Yvonne de Carlo, Cedric Hardwicke, John Carradine, Vincent Price and Edward G. Robinson. As well, the production featured 30,000 extras and 15,000 animals.

DeMille’s first choice for Moses had been William Boyd, a sixtyish actor known for his roles in Hopalong Cassidy and other Westerns. No matter that Moses was 80 years old at the time of the Biblical Exodus, Boyd was likely too old for the role. Fortunately he turned it down and it went to the younger and more virile Heston, who also voiced the speaking part of God. The baby Moses was played by Heston’s own infant son.

Much of the production was shot on location in Egypt. For the Exodus scene, which showed throngs of Hebrews leaving Egypt, entire local villages were hired to take part.

“The Exodus stands out as the most crowded crowd scene in movie history,” Louvish writes, noting that some 20,000 or 30,000 costumed extras — real people, not computer-generated images — are visible in the great overhead crane shot in which the freed slaves move out below the stone gods of Egypt into the desert.

DeMille relied upon a team of six scriptwriters, one of whom, Jesse Lasky, Jr., claimed he was regarded as “the company Hebrew” even though he knew more about Christianity than his own birth religion. “I want you to write me the first feast of Passover,” DeMille would tell him. “Write it from the heart of a Hebrew . . . You’ve got to dig. Into yourself. Your ancestors.”

DeMille relied upon a team of six scriptwriters, one of whom, Jesse Lasky, Jr., claimed he was regarded as “the company Hebrew” even though he knew more about Christianity than his own birth religion. “I want you to write me the first feast of Passover,” DeMille would tell him. “Write it from the heart of a Hebrew . . . You’ve got to dig. Into yourself. Your ancestors.”

DeMille was not always pleased at the result. More than once, he accused Lasky of reducing a great moment in the saga of mankind to Hollywood theatrics as he angrily tore up pages of script. Even so, the shooting script added much Hollywood claptrap to the Biblical tale.

The sixteen cameras used during production churned out enough footage for ten pictures. The finished product was an extraordinary three hours and 39 minutes long, but only four of the ten plagues — blood, hail, darkness, and the death of the first-born — appeared on screen. The “coup de cinema,” of course, was the parting of the Red Sea, achieved using a tank at the Paramount lot with ramps of cascading water, superimposed with matte paintings and clever miniatures. Louvish called it “a state-of-the-art cinematic miracle.”

The film has earned $838 million to date, making it the fifth-highest grossing movie made in the United States. Astonishingly, it won only a single Academy Award, for visual effects. The 1956 Oscar for best picture went to Around the World in 80 Days, while the Oscar for best director went to George Stevens for Giant.

Film buffs will enjoy the book for its insights into the career of a great director and the vanished age of the Hollywood epic. ♦

© 2008