Making Men Out of Street Arabs

By W. F. Wiggins

From Toronto Saturday Night Magazine, December 1, 1906

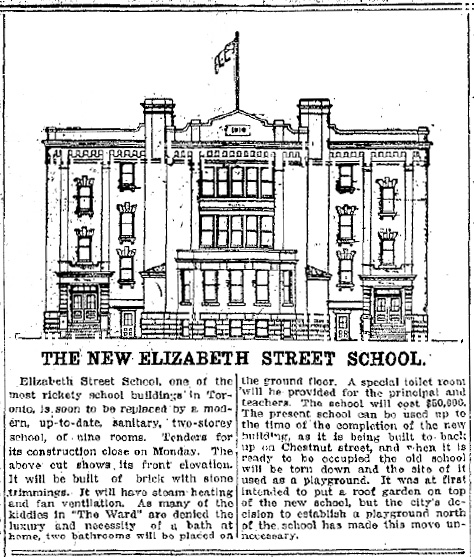

From an educational standpoint there is no more interesting institution in Toronto than the Elizabeth street public school, popularly known as “the school of the Ward.” Here have been taught and trained some of the worst boys that have been bred in the slums of Toronto, and here have been educated and developed some of the brightest and brainiest chaps that have gone forth in the world to seek fame and fortune.

From an educational standpoint there is no more interesting institution in Toronto than the Elizabeth street public school, popularly known as “the school of the Ward.” Here have been taught and trained some of the worst boys that have been bred in the slums of Toronto, and here have been educated and developed some of the brightest and brainiest chaps that have gone forth in the world to seek fame and fortune.

To the tact and training of the teachers of this school belong the credit for transforming some of the toughest of the tough into decent law-abiding citizens. Miss H. How, who has been principal of the school for some twenty years, is probably the pioneer of this class of educational work in Toronto.

It was in the days when W. H. Howland was Mayor of Toronto that he and Inspector James L. Hughes took a walk through the Ward one Sunday. The Mayor was interested in mission work in the Ward, and they were on the hunt for cases of need. In an out-of-the-way corner of a lane they found a tumble-down sort of a hut without windows or doors. It was the rendezvous — or the home — of a gang of young thieves. Their average age was about 15 years. All they had to eat were a few herrings and couple of loaves of bread. These, they confessed to the visitors, had been stolen. There was some parlaying between the Major and the Inspector and the captain of the gang — for they had elected the biggest chap among them as their leader — and it was finally agreed that the amateur desperadoes should go to school, if a suitable school could be found. A small mission hall was secured. Then came the most important question — who should be the teacher?

“Give us the best man you’ve got,” said Mr. Howland to the Inspector.

“Give us the best man you’ve got,” said Mr. Howland to the Inspector.

“Haven’t got a man on the staff good enough for the job.”

“How’s that? I thought you had the best teachers in Ontario.”

“Yes, but for this class it’s a woman you want,” declared the Inspector. After considerable argument he convinced the Mayor that a woman should teach the young toughs.

Miss How was chosen for the work. She had had some experience with a roomful of almost uncontrollable youngsters of the Ward, and she had to nail up the doors and windows at times to keep them in the room. She had succeeded well enough to give reason for the faith that Mr. Hughes had in her. He made it a condition of her appointment to the new class that she should not thrash one of them under any circumstances. If anything very bad had occurred she was to report it to the Inspector.

Miss How got away to a good start, but the trouble soon came. Mike, the younger brother of the leader, was a particularly foul-mouthed fellow, and, becoming vexed at the teacher, he called her a vulgar name. She said nothing, but lost no time in notifying Mr. Hughes. He deemed that there was need for immediate and strenuous action. He is no advocate of corporal punishment, but this case was out of the ordinary.

“I will have Col. Thompson go there on Friday afternoon and give Mike the thrashing he deserves.”

Col. Thompson went, he saw, but he did not conquer. He was just about to thrash Mike when the slates began to fly about his head. Things were coming his way and taking advantage of the momentary confusion, Mike made a flying leap through the window. That ended the incident for that day.

The next Tuesday Miss How heard a timid knock at the door. She opened it and was surprised to be greeted by Mike. “I want to come back to school please, Miss How.”

“You cannot come back till you take your thrashing.”

Mike went sorrowfully away. Next day the timid knock was repeated. It was Mike again. Again he was given the same answer. But he was yearning to get back to school.

“Say, Miss How, if you’ll let me come back to-day I’ll be here on Friday to take the trashing.”

“You give me your word of honour?”

“That’s straight on the square.”

And Mike went into school. Friday came. So did Col. Thompson. Mike took his thrashing like a little man, and Col. Thompson will testify that it was one of the good old-fashioned sort. But the incident had its effect on the whole class.

Mike was reclaimed from his evil ways, more or less. He is now employed in Toronto as a driver for a well-known firm.

* * *

Another well-known character of the school was a young Irish lad, whose parents spent more than half their time in jail. Neither of them were willing to work, and from his earliest years the boy had to make his way in the world alone. On a bitterly cold winter night one of the teachers of the school discovered him at the Union Station, trying to sell a bundle of papers. He had not enough money to get a night’s lodging at the dive on Pearl street where he was in the habit of sleeping, and there was not a soul in sight to buy his papers. The teacher took him to his disreputable lodging place, and paid for his bed. Then she tried to coax him to come to school. At last, after trying all known methods of persuasion, she induced him to promise to come. He came, and he gave her all sorts of trouble. The lad had been born and bred in an atmosphere of crime, he had been in jail more times than he was years old, and little could be expected of him. He could not speak without using foul language or profanity. But time and tact and teaching wrought wonders with him, and he grew to love the school and the teacher.

Another well-known character of the school was a young Irish lad, whose parents spent more than half their time in jail. Neither of them were willing to work, and from his earliest years the boy had to make his way in the world alone. On a bitterly cold winter night one of the teachers of the school discovered him at the Union Station, trying to sell a bundle of papers. He had not enough money to get a night’s lodging at the dive on Pearl street where he was in the habit of sleeping, and there was not a soul in sight to buy his papers. The teacher took him to his disreputable lodging place, and paid for his bed. Then she tried to coax him to come to school. At last, after trying all known methods of persuasion, she induced him to promise to come. He came, and he gave her all sorts of trouble. The lad had been born and bred in an atmosphere of crime, he had been in jail more times than he was years old, and little could be expected of him. He could not speak without using foul language or profanity. But time and tact and teaching wrought wonders with him, and he grew to love the school and the teacher.

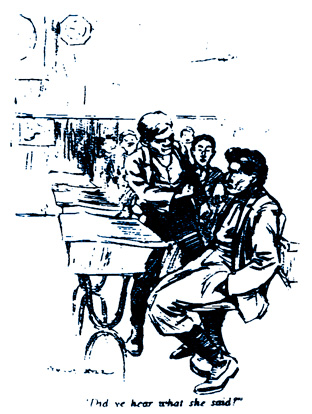

It happened one day that owing to the illness of the teacher a substitute was sent to the class. A big Syrian fellow, surly in disposition, determined to take advantage of the occasion, and do as he pleased. The teacher ordered him to take some part in the exercises. He, seated in the front row, promptly refused. The command was repeated. The Syrian then bluntly admonished the teacher to visit the warm region that Dr. Torrey talks about. There was silence in the room for a minute. This sudden defiance of law and authority astonished the class. Then came the quick steps of the Irish lad up the aisle to the front. He confronted the rebel bully, his fists clenched in threatening manner and his purpose showing plainly in his face.

“Did ye hear what she said?” he demanded in firm even tones.

“None of your business,” growled the Syrian.

“Did ye hear what she said? Now do it right away or by all the powers I’ll heave ye down the stairs.”

The big fellow rose from his seat. Pat’s fists at his face, and did as the teacher directed him. There were no more rebellions in the class room while the little Irishman was there.

He has since developed into one of the most decent and well-behaved young men about this city.

The boy was an inveterate cigarette fiend. He almost lived on the little white things, and he was up-to-date in all the latest drinks. When he was at school he would often raise his hand to ask permission to go out. The teacher knew why. “I know you’re going out to smoke, Pat,” she would say. “But you must not smoke in the school yard. Go to the street.” Pat would go, and an hour afterwards he would come back, refreshed and ready for work. Gradually, though, he fought the cigarettes till he conquered them. “It was the most terrible battle I ever saw a human being fight — the battle of that boy with the habit,” is the evidence of his teacher. Pat also gave up drinking, and mended his language. He now holds a responsible position and was happily married not long ago.

* * *

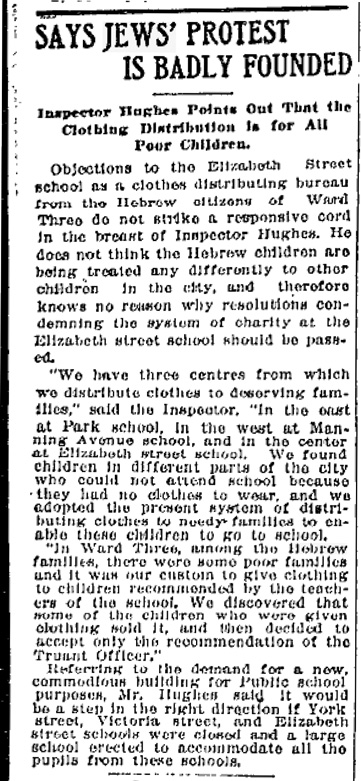

Elizabeth street school, however, is more than an educational institution. It is a center for the dispensing of charity. Money and clothes are handed out to the poor as the most needy cases come to the attention of the teachers, and the latter go about in the Ward along its most dirty streets and up its lanes and alleys seeking for a boy or a girl whose face has been missed at school, and incidentally coming across case after case of most pitiable misery.

Elizabeth street school, however, is more than an educational institution. It is a center for the dispensing of charity. Money and clothes are handed out to the poor as the most needy cases come to the attention of the teachers, and the latter go about in the Ward along its most dirty streets and up its lanes and alleys seeking for a boy or a girl whose face has been missed at school, and incidentally coming across case after case of most pitiable misery.

“We have practically to mother and father some of the families in the Ward,” said one of the teachers, “and we enjoy the work. Don’t put us down in the class of people who go about doing a bit of charity here and there and talking all the time about their self denial. Nothing of the sort here. We enjoy it. We find it interesting. We like to go about and see for ourselves how the people are living, and that’s the only way we can find out how we can best help them. No, it’s not self denial.”

Husbands and wives, who have been taught in the historic school often come back to it yet to tell their tales of woes, sometimes of marital infelicity, to the teachers who have known and guided hem from their youth up to manhood and womanhood. The teachers, as we mentioned before, need tact and lots of it. They hear both sides of the story, and then they do all they can to get man and wife back again on the old footing of peace and comradeship.

As charity dispensers the teachers have grown worldly just by virtue of long experience. Many are the forms of fraud and deceit which are tried on them, and at first they fell easy victims to his tear-stained face and pleading voice, and a tale made up for the occasion. One woman once came to the school with a pitiable tale to the effect that her husband had been out of work for some time, and had pawned his tools. Now he had a chance to get work. Could she get $2 to get the tools out of pawn? She got the money. The same afternoon one of the teachers saw the woman walking up the street with a pail in her hand and, following her to the miserable shack that the poor creature called home, she found the applicant for charity acting as hostess at a beer drinking social. Three other women were enjoying the expenditure of the $2.

As charity dispensers the teachers have grown worldly just by virtue of long experience. Many are the forms of fraud and deceit which are tried on them, and at first they fell easy victims to his tear-stained face and pleading voice, and a tale made up for the occasion. One woman once came to the school with a pitiable tale to the effect that her husband had been out of work for some time, and had pawned his tools. Now he had a chance to get work. Could she get $2 to get the tools out of pawn? She got the money. The same afternoon one of the teachers saw the woman walking up the street with a pail in her hand and, following her to the miserable shack that the poor creature called home, she found the applicant for charity acting as hostess at a beer drinking social. Three other women were enjoying the expenditure of the $2.

And the same holds true regarding the giving of clothes. There is one woman who makes a practice of bringing poor people who are almost naked to the school to get clothing, simply in order that she might get a chance to rummage through the clothes closet and choose the garments herself. Then she would take them to a pawnshop, and get a few coins with which to buy liquor.

Money and clothes — principally clothes — kept pouring into the school, and both of these precious commodities are kept on the move.

“We are constantly giving them away, as we are never in want of them,” said a teacher. “People seem to know that there are hundreds of deserving cases where charity could be wisely expended, and they send us the wherewithal to do it for them. We’re glad to do it.”

There are cases, however, where it is hardly wise to give charity. On one occasion, when one of the pupils died, the teachers sent $5 to the bereaved family. Though they were in need of both clothing and food, the money was spent in hiring extra hacks for the funeral.

In another case where there was a death, another $5 gift was sent, this time after the funeral was over. It was expended in buying costly silver lettered funeral cards.

At times the teachers run more than slight risk in their visits to homes which have not too good a reputation. One of them went into a house on Agnes street some time ago in search of a boy who had not come to school regularly. She was shown upstairs and there found the mother of the lad in a drunken stupor. She talked to the maudlin creature for some time and tried to sober her somewhat and get her to realize that she ought to look after the lad. At last she rose to go, and the woman staggered toward the stair to accompany her. “Never mind coming, “Mrs. ,” said the teacher, fearing that the woman would fall down stairs.

“Yes, I’ll come, for they may not let you out if I don’t,” was the reply. The teacher wondered at it. When she came down stairs she understood. A big six-foot square-shouldered fellow stood leaning up against the door, smoking. The teacher walked across the room and made an effort to pass him. “No, you don’t,” said he in threateningly surly tones. “You’ll have to pay for your footing before you get out of here.” Now it happened that the teacher had no small change on her at the time. If she had she would probably have handed it over. She had in her pocket — for she, being an extraordinary woman, had a pocket — a roll of bank notes, which was well nigh all her worldly wealth. She was resolved not to let the roll be seen, for a part of it would not do in that event. So she put on a brave face. “Pay nothing,” said she. “Let me pass.” But the man was obdurate. The woman she had come to see protested, but in vain. Another man came from the adjoining room and backed up the big fellow. Then another woman came on the scene. She was the wife of the six-footer. “Let her go,” she advised. “That woman is a school-teacher, and trouble will come of this, I tell you.” The man at the door made a rush at her. He was in a rage at the thought of having to let his supposed prey go, and in a moment the whole four inmates of the place were engaged in a free-for-all fight. The teacher took advantage of the sudden turn of events to slip out the door and away. All this happened in a house almost in the shadow of No. 2 Police station, on Agnes street. The teacher has since been careful not to carry money with her on such visits, and not to go into suspicious places after dark.

* * *

A pleasing feature of this school is the wholesome respect, and in some cases, the love which the pupils manifest for their tutors. A little fellow named Jack Palmer, who lived in a shed in the rear of a Center avenue house, thought so much of his teacher that when he was down on his knees in the street, shining shoes, he would jump to his feet and take off his ragged cap if she happened to pass by.

A class of seven boys wept bitter tears when they were told that they were promoted and could be taught no more by the teacher they had learned to love.

One young fellow went out West, after leaving school, and not long ago the teachers heard from him. He had a good position on the C.P.R. in British Columbia, and invited them to come out and visit him. If they would come he would arrange transportation for them, and pay their expenses out there.

The same chap was one of the most uncontrollable boys in the school. His favourite amusement was to get out of his seat and stand on his head on his desk, to the immense entertainment of the whole class. Once there was a map to be hung on the wall, and the lad volunteered to hang it with his toes while he stood on his head. Just to see if he could the teacher let him try, and there were thunders of applause from the appreciative juvenile audience when the feat was accomplished.

* * *

Elizabeth street school boasts a large number of rather clever pupils. The children of the foreigners — particularly the Jews — are remarkably quick to learn. One 11-year-old lad, Sammy Stork, the son of the official chicken killer of the Toronto Hebrews, has gone as far as he can in that school and is now taking up higher work in Wellesley street school. He has never been a full week at school in his life, and he has already conquered the first book of Algebra. He is quick enough in calculating to multiply a number in four figures by another of three, and to do it without recourse to paper or pencil. He still goes back to his old teacher at Elizabeth street, Mrs. J. M. Warburton, for his algebra lessons, which he gets after the regular school hours.

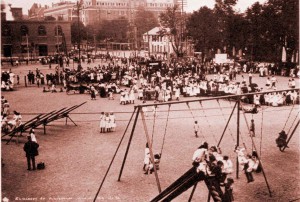

In the summer holidays all the pupils at the school who can go, get a chance to spend a couple of weeks or more in the country. Last summer some 450 little lads and lasses were sent away at no coast whatever to themselves or their parents, if the latter did not care to contribute. The funds went in to the school are sufficient for the work. “We never ask, and we never have to ask. We are never short,” said one of the teachers.

In the summer holidays all the pupils at the school who can go, get a chance to spend a couple of weeks or more in the country. Last summer some 450 little lads and lasses were sent away at no coast whatever to themselves or their parents, if the latter did not care to contribute. The funds went in to the school are sufficient for the work. “We never ask, and we never have to ask. We are never short,” said one of the teachers.

The scheme originated some years ago when the teacher determined to send half a dozen poor children, who were ill, to the country for a fresh air outing. By announcements from country pulpits and other similar means the fact was advertised that there were poor children who were in need of a place to go for a couple of weeks. The response from the farmers was a ready one, and the next year a larger number were sent. So the thing grew until last summer practically the whole school went. The railway companies carry the children for a small fare and the cost is not more than $1 per head.

The children are sent away in “batches” of from twenty to thirty. Each one “tagged,” which means that each wears a small pasteboard card bearing the child’s name and address, and its destination. A responsible person is sent with each party and he sees that the youngsters are dropped off at the stations they are destined for. Then when their time is up he goes along the line again, picks them up and brings the party back to Toronto. When the boys and girls come back they are invariably loaded down with animal pets, rabbits, pigs, kittens, puppies and chickens being the favourites. The children are sent as far north as Gravenhurst, west as far as Sarnia, and eastward to Kingston and Belleville.

One little city girl, who had never been in the country, did not know the source of milk until she was sent to a farm in this way. She was so horrified when she learned that it came from a cow that she has steadfastly refused to drink or sup of it ever since.

* * *

If the children of the Ward are dirty it is not the fault of Elizabeth street school. A big bath tub has been installed there, and the little tots as well as the bigger chaps are given a chance to take a dip. They take to the water wonderfully well, and seem to enjoy a splash. Some there are who do not look upon it so favourably, but when a teacher notices that any pupil needs a wash she is diplomatic. “Johnnie,” she will say, “you have been very good to-day. You may take a bath.” And Johnnie, deeming from the teacher’s tone that it is a privilege, goes to the bathroom. Sometimes the room is so much in demand that two go in at once. ♦