Faced with a non-negotiable deadline of March 31, 1999, an army of some 1,200 data entry clerks, software technicians, Holocaust scholars and other specialists worked at a feverish pitch through late February and March to computerize the names of three million or more Holocaust victims from a collection of documents at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem.

Faced with a non-negotiable deadline of March 31, 1999, an army of some 1,200 data entry clerks, software technicians, Holocaust scholars and other specialists worked at a feverish pitch through late February and March to computerize the names of three million or more Holocaust victims from a collection of documents at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem.

Spurred into action by an $8 million (US) allocation of funds from the Swiss Bankers Association and the World Jewish Congress, Yad Vashem officials initiated a massive mobilization of manpower, took over a whole floor in an office building in the Jerusalem suburb of Givat Shaul, and rented more temporary space in Be’ersheba for the duration of the project.

The Swiss Bankers Association and the World Jewish Congress, acting jointly as the Volcker Commission, are funding the project in order to attain a comprehensive list of names of Holocaust victims to compare with a list of dormant Swiss bank accounts that may have belonged to Jews killed by the Nazis during WWII.

Recognizing that a need might eventually arise for a thorough inventory of Holocaust victims, Yad Vashem officials began to conceptualize such a project years ago, but only went into high gear after the Volcker Commission funding arrived in early January.

“It’s a fascinating convergence of interests,” said Dr. Ya’acov Lozowick, director of the Yad Vashem archives. “We’ve been dreaming of this for a long time and would have done it at our own sedentary rate until the Volcker Commission came along and wanted it done right away. Yad Vashem could have lived with doing this over two years. But if it has to be done in three months, then so be it.”

Beginning in January (1999), Israel’s famous Holocaust institution spent at least six weeks in detailed logistical planning and hired an outside firm to find and train manpower, and a software company, Softel, to design a specialized software tool to handle the more than three million Pages of Testimony that it has collected from relatives of Holocaust victims since the early 1950s.

Workers at Yad Vashem began in early February to feed some 50,000 Pages of Testimony through two high-speed scanners every day; the scanners are specially adapted to handle fragile material. Meanwhile, 14 teams of data entry clerks in Jerusalem and Be’ersheba were working from early morning to late at night to keyboard in details from the handwritten Pages of Testimony, whose high-resolution scanned images appeared on their screens.

“The assumption is that the students will be doing a page every four minutes,” said Lozowick in late February. “So far, that hasn’t happened yet. . . . Our assumption is that a couple of weeks down the road, the data entry will be done around the clock. The teams will probably work in shifts from Saturday night to Friday afternoon, stopping only for Shabbat.”

“The assumption is that the students will be doing a page every four minutes,” said Lozowick in late February. “So far, that hasn’t happened yet. . . . Our assumption is that a couple of weeks down the road, the data entry will be done around the clock. The teams will probably work in shifts from Saturday night to Friday afternoon, stopping only for Shabbat.”

Recognizing the inevitability of transcription errors and difficulties in reading the Hebrew, English, Polish and other languages in which the Pages of Testimony were originally scrawled, Yad Vashem officials devised a thorough system of checks. Whenever a surname or place name is entered for the first time, for instance, that particular record was electronically sent upwards to one of a hierarchy of specialists, who checked it against thorough master lists, in an Oracle database, that the institution has compiled over many years.

The specialists also have at their fingertips lists of vocations, family relations, family status and titles in as many as 12 languages. Entering the English word “shoemaker,” for example, produces a chart showing translations of that vocation into a dozen languages, including four variants in the Serbian tongue alone.

Giving a demonstration of the software, Lozowick called up a page of testimony onto the screen of his computer. The surname, Zoli, was highlighted in a yellow square, indicating that the system hadn’t encountered that name as yet. A pull-down box beside the name automatically suggested alternate spellings, beginning with Zoly.

Neither did the computer recognize the spelling of the town name of Klosenburg, suggesting instead the accepted spelling of Klausenburg.

Lozowick made both linkages, and sent the page “upstairs” to be checked by separate experts in surnames and geographic locations.

In a separate room, a geographic locations expert named Shaul resolves questions regarding the proper identity and spelling of localities by referring to Yad Vashem’s computerized “Geographic Names Index” of some 50,000 place names culled from a variety of sources, including the reference work by Gary Mokotoff and Sallyann Amdur Sack, Where Once We Walked.

Yad Vashem specialists may also engage in “data mining” from the data itself, allowing them to establish correlations, for example, between names and places. In Hungary, for instance, Jews named Abraham apparently often used the name Adolf in official documents, such as when opening bank accounts.

The software used for the project is updated almost daily, and sometimes even twice a day. “Now we’re on version 17 of the software,” Lozowick said. “This morning we were on version 16, and yesterday morning we were on version 13. It looks nice and calm around here but believe me, there’s nothing calm about this place.”

Standing at the front of a large room in which some 70 data entry clerks were sitting at computer terminals arranged in a large U-formation, Lozowick seemed as busy as an army general, one moment engaged in brisk dialogue by cellphone, the next inspecting a minor software glitch on his laptop computer.

Had he and his team encountered any unexpected problems? “Yes — about 25 a minute,” he admitted. “Actually, today is the first full day where everything seems to be working well. The software didn’t screw up and the data entry people seem to know what they’re doing. At the moment, everything seems to be running smoothly.”

Yad Vashem recently turned over to the Volcker Commission a list of the first one million names, which were immediately matched with existing lists of owners of dormant bank accounts. Using only the simplest methods of matching, some 3,000 dormant bank accounts were identified as having belonged to Jews who perished in the Holocaust. According to Lozowick, more accounts will be identified now that Yad Vashem is employing its computerized lists of variants of names and locations.

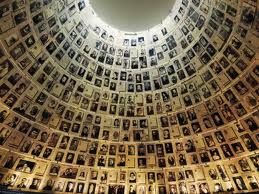

As part of its overall effort to compile a comprehensive computerized inventory of Holocaust victims, Yad Vashem has gone far beyond the Pages of Testimony located in the facility’s Hall of Names. It has also drawn up a master list of some 8,163 other lists of Holocaust victims, containing a total of more than 12 million occurrences of names.

Nearly 2,000 more lists compiled by the Red Cross’s International Tracing Service in Arolsen, Germany, contain an additional six million names, bringing the total on Yad Vashem’s “List of Lists” to roughly 18 million occurrences of names on some 10,000 lists.

The lists include many duplicates — for instance, a Czech Jew who possessed a Generali life insurance policy, had a business confiscated, and was eventually deported to Theresienstadt and then Auschwitz and Dachau, might show up five times — but Lozowick asserts that they make it possible, for the first time, to name at least five of the estimated six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

“Until we did the list of lists, we didn’t know we had this data,” he said. “We found out to our surprise that we had far more data than anyone, including ourselves, had realized.”

Yad Vashem’s computerized “List of Lists” resembles a spreadsheet entry that extends across some 38 fields of data to offer a detailed summary of what each list contains. Checkmarks indicate whether a given list supplies a date of birth, place of birth, occupation, or any indication of family relations for each victim, and so on. Other columns indicate whether the information on a given list bears any relevance to banking, confiscated property or insurance issues.

Yad Vashem is making every effort not to duplicate the smaller-scale computerization efforts of other institutions such as Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation and the United States Holocaust Museum and Memorial, Lozowick said. “Any of these institutions that give us the results of what they’ve done, we give them what we’ve done. It’s a win-win situation.”

So far, according to Lozowick, Yad Vashem has entered into co-operative arrangements with about eight institutions, including the Bergen-Belsen Museum which has provided a list of 23,000 Jewish inmates, and the Swiss Federal Archives which has supplied a list of 24,000 names of Jews who entered Switzerland during the Nazi era.

He indicated that Yad Vashem would waste no efforts in computerizing lists that have already been computerized by others, such as the 128,000-name German Gedenkbukh.

As they prepared to turn over some two million computerized names to the Volcker Commission by March 31, Yad Vashem officials were engaged in discussions with other sponsors to allow the project to continue beyond that date. “We’re making a huge effort not to have this massive effort grind to a halt in April,” Lozowick said.

He indicated that Yad Vashem was planning to make its computerized list of Holocaust victims easily accessible to the public, most likely via the internet, before the end of 1999. ♦

Originally distributed by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. © 1999