by Irving B Rosen, MD, FRCSC

Society doctors, like Harley Street specialists, evoke the image of the sought after, affluent doyen of their calling, courted by the high and mighty, who never question their high fees.

Toronto had its society doctors who held sway for about fifty years from about 1900 to 1950. I became acquainted with a society doctor as an eight-year-old patient in the days before penicillin, when pneumonia bore a stigma of lethality.

Dr. Joe Chaikoff came to my home, cheerily examined me, reassured all, and prescribed an antipyretic like Dover’s Powders and left. That left my parents unsatisfied and they called for a specialist. On a Saturday morning the head pediatrician of the Sick Kids Hospital, Dr Allen Brown, showed up and repeated the examination and opinion. My factory worker father paid a fee and all was well.

This incident characterized Toronto’s society doctors, the role they played and how they were regarded by their clientele. They did not deal with the hoi-polloi but the working class members of the Jewish mutual benefit societies which were an essential presence in Toronto’s Eastern European Jewish immigrant social life.

Around the turn of the century North America was inundated by European immigrants, who were seeking a better life. This exodus was facilitated in the 1870s by new safe steam travel which reduced Atlantic travel time from six weeks to seven to ten days. Steamship lines were in active competition for lucrative immigration business, enlivening the ports of many cities. The United States was the favoured destination: some 12 million people were processed at Ellis Island between 1892 and 1914.

Canada had its share particularly since its 1896 prime minister, Sir Wilfred Laurier and his immigration minister, Clifford Sifton were anxious to populate the thinly settled West. But Sifton did not favour Jews, Africans, or Chinese who had to pay a head tax This attitude was enhanced by Dr Clarke of Clarke Institute fame, the first professor of Psychiatry and dean at the U of T medical school, eugenicist and immigration screening activist, who said when rejecting the intake of Jewish orphans, “They belong to a very neurotic race,” a sentiment reverberated by the notorious Blair of “none is too many” fame.

Canada had its share particularly since its 1896 prime minister, Sir Wilfred Laurier and his immigration minister, Clifford Sifton were anxious to populate the thinly settled West. But Sifton did not favour Jews, Africans, or Chinese who had to pay a head tax This attitude was enhanced by Dr Clarke of Clarke Institute fame, the first professor of Psychiatry and dean at the U of T medical school, eugenicist and immigration screening activist, who said when rejecting the intake of Jewish orphans, “They belong to a very neurotic race,” a sentiment reverberated by the notorious Blair of “none is too many” fame.

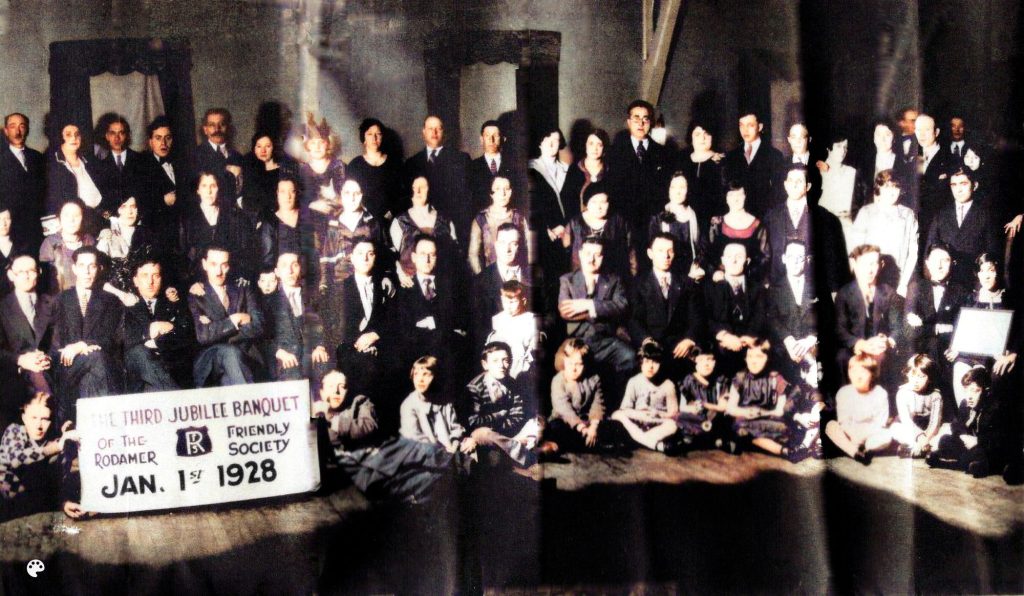

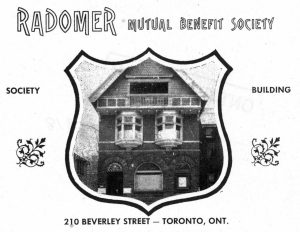

Immigrants of all ethnicities set up mutual benefit societies to provide sickness, unemployment, death, credit benefits as well as socialization. Gladstone and Speisman described about 70 Jewish mutual benefit societies that were formed on a general fraternal help basis, or common European origin such as the landsmanschaften, or ideology like the socialist Arbeiter Ring, or even a union local. Some societies went on to organize synagogues, after-school Hebrew and Yiddish schools, or summer camps. By 1930, Jews made up as much as seven to eight per cent of the Toronto population and initially lived in the “Ward,” a centrally located slum bounded by University, College, Queen and Yonge Streets. Public Health Dr Hastings’s 1911 report of its unfit, despicable nature led to its eventual removal and replacement with Nathan Phillips Square, the New City Hall, and elements of two universities, four teaching hospitals, hotels, and multiple high rises that now occupy the same space.

The Jewish mutual benefit societies offered unique medical plans that rejected a fee-for-service arrangement in favour of low monthly or annual premiums that would entitle families to summon a doctor an unlimited number of times. If a participating doctor failed to respond to a call and the patient called a second doctor, the initial doctor was obligated to pay the fee. But generally there was a competition for such positions and MDs would curry favour with members by throwing “katshke” parties. The successful doctor was known as a society or lodge doctor.

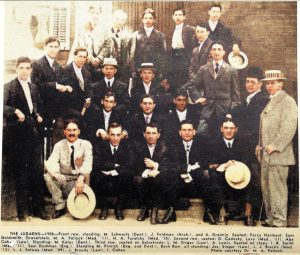

This scheme limned the history of the first doctors of Jewish descent to be educated at the University of Toronto. They were the progeny of the Eastern European Jewish immigrants, like their clientele, whose fathers typically worked in the clothing factories of the T. Eaton Company or Tip Top Tailors, or were shopkeepers, junk dealers or pedlars.

Admission to U of T medical school was purportedly by senior matriculation and ability to pay the school fees. Selection committee minutes from 1944, uncovered by Med History Professor Ned Shorter, clearly indicated that a quota existed for Jews and women. Furthermore, opportunity to obtain postgrad education by internship was denied Jewish grads. The Toronto General Hospital in 1929 would accept one and only one such grad on an annual basis. Other Jewish grads had to go to the United States or lesser hospitals to complete their education. The Jewish students related well with classmates but they brought a different ethnic and class presence to the school since their classmates’ parents came mostly from a professional or business class.

The Society doctors were the first of their kind to obtain a high school degree, never mind a medical education, and every Jewish family practitioner of that time considered becoming a society doctor to ensure practice success. Unlike their non-Jewish colleagues, the emerging doctor was new, untried in practice, lacking hospital or institutional affiliations, and felt uncertain of his appeal to the non-Jewish patient. For all these reasons he felt vulnerable and receptive to becoming a society doctor. All the major participants have passed away, and while no definitive account is available, the memoirs of four physicians and a smidgeon of comments by observers can give us some idea of what transpired.

Dr A.I. Willensky, son of immigrants, was a 1908 U of T grad and obtained postgrad experience by doing a rural locum tenens and taking courses at various institutions. Using a horse and buggy he started practice in 1910. In his 1950 book “A Doctor’s Memoirs,” he stated, “Building up a practice can go very slowly. Yet for some of us in Toronto work proved overwhelming from the outset as a lodge or society doctor .All the members of a lodge paid a dollar a year towards their doctor’s salary. The doctor was obliged to respond to every call. If he failed to go himself he had to meet the cost of whatever regular physician the patient consulted. A lodge doctor was like a first aid man. Non Jewish doctors too, often took on a lodge weighing advantages against the modest salary. I was a poor lodge doctor. Instead of authoritative answers they wanted, I would go on sorting symptoms in my mind. People would demand a real doctor, a big man. Well they were worried and for all my bulk, I was, after all, only the lodge doctor.”

Dr A.I. Willensky, son of immigrants, was a 1908 U of T grad and obtained postgrad experience by doing a rural locum tenens and taking courses at various institutions. Using a horse and buggy he started practice in 1910. In his 1950 book “A Doctor’s Memoirs,” he stated, “Building up a practice can go very slowly. Yet for some of us in Toronto work proved overwhelming from the outset as a lodge or society doctor .All the members of a lodge paid a dollar a year towards their doctor’s salary. The doctor was obliged to respond to every call. If he failed to go himself he had to meet the cost of whatever regular physician the patient consulted. A lodge doctor was like a first aid man. Non Jewish doctors too, often took on a lodge weighing advantages against the modest salary. I was a poor lodge doctor. Instead of authoritative answers they wanted, I would go on sorting symptoms in my mind. People would demand a real doctor, a big man. Well they were worried and for all my bulk, I was, after all, only the lodge doctor.”

Dr David Eisen graduated in 1922 from U of T medical school and was also a university wrestling champ. His immigrant dad came to Canada, alone, at age forty-two and returned after two years to bring back a wife and six children. Dr Eisen trained in the United States in radiology, returning to practice in Canada. In his 1980 book, “A Diary of a Medical Student,” he wrote, “In Toronto in those days the going was pretty tough for a new doctor in any field. Despite the rising stock market in the latter half of the twenties, conditions for the young general practitioner were particularly bad.

Dr David Eisen graduated in 1922 from U of T medical school and was also a university wrestling champ. His immigrant dad came to Canada, alone, at age forty-two and returned after two years to bring back a wife and six children. Dr Eisen trained in the United States in radiology, returning to practice in Canada. In his 1980 book, “A Diary of a Medical Student,” he wrote, “In Toronto in those days the going was pretty tough for a new doctor in any field. Despite the rising stock market in the latter half of the twenties, conditions for the young general practitioner were particularly bad.

“This was due to the fact that their practice was largely tied up with sick benefit lodges to which workingmen belonged. The doctor had to contract with these societies that for a small sum of about $4.00 to $6.00 he would render medical care to the patient and his family for a year, and to acquire this doubtful privilege, the young doctor had to compete with other doctors to be elected as a lodge doctor. Aside from the low rate of remuneration, there were certain indignities which the doctors felt were unnecessarily associated with the position. In 1938, a long step towards the solution of the lodge problem was made with the formation of the central medical bureau.” Dr Eisen also felt that becoming a society doctor discouraged young grads from starting practice in Toronto.

Dr Isadore Tepperman, a 1938 U of T med grad, had earned math scholarships and wrote about pertinent memories at my request. His immigrant dad earned his living by being a pedlar in the farming communities of Todmorden and Lake Wilcox. He wrote:

“After I married, my father-in law, a very strong union member as well as a lodge member, insisted I become a lodge doctor. One day I was invited to a full membership meeting of his lodge, was introduced and promised to be a reliable doctor and was elected as one of their doctors. While many lodges had one favourite old-time doctor several had two, giving the membership a choice. Each member would let the secretary know which doctor he preferred. A list would be drawn up and I would start to see the member and/or his family in my office.

“At one time I had a fairly large panel in some three lodges. The fee schedule was $10 per year for a single member and $24 for a whole family, both office and house visits, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. The average cheque was usually a few hundred dollars monthly for a great deal of time and effort. It was clear that one could not make a living from a lodge practice alone. We could charge for injections, fancy dressings, a cast, but the member was unhappy to pay for anything.

“Over the years I built up a non-society practice. I also found that my lodge clientele praised my services but at the same time would seek out other doctors behind my back and I would often be the last to hear that he or she had a consultation or operation with another doctor. One of the last straws came when I heard a society ‘yachna’ refer to us society doctors as little petty ignorant doctors. After thirteen years in the lodge doctor business, in 1952, I sent in a letter of resignation. I felt the time had come for me to leave a poorly paid and at times degrading practice situation. I have never regretted it . . . .”

Dorothy Dworkin

Dr Coleman Solursh, a 1931 grad and a member of AOA, a medical fraternity for honor students, had to obtain his internship in the United States. He was interviewed for the Ontario Jewish Archives by M. Silbert in 1985. His father came to Canada in 1904 from Poland and worked as a tailor at the T. Eaton Company. Dr Solursh, active in credentialing efforts for family practice, as well as U of T alumni affairs still expressed anger sixty years after graduation at the bias in medical student selection and his denial for postgrad training in Toronto requiring American dislocation. He further smouldered heartfelt resentment about the need of being a society doctor because of its inadequate rewards for service as well as humiliation experienced at the hands of some patients.

I also spoke to two children of established society doctors. The late Jenny Volpe Klotz, the mother, wife and daughter of physicians, recalled with anger how her father had been awakened at night for a society house call. Dr Volpe then ascertained the complaint, a headache had been longstanding and suggested a morning office visit. He was then threatened with society dismissal for non compliance. Dr Eli Markson recalled his father Dr Charles announcing at the dinner table, with great relief, that he was finished with society practice.

In 1925 forty Jewish MDs who had been trained by the U of T and predominantly practised as society doctors, got together and formed the Jewish Medical Society. They held monthly meetings at their homes for socialization, scientific papers and also to discuss society practice concerns. Secretarial minutes were kept and available through the Ontario Jewish Archives. The group was established shortly after the formation by Dorothy Dworkin and the Ezras Noshim Women of the Mount Sinai Hospital in a converted large home on the now-swish Yorkville Avenue.

In 1925 forty Jewish MDs who had been trained by the U of T and predominantly practised as society doctors, got together and formed the Jewish Medical Society. They held monthly meetings at their homes for socialization, scientific papers and also to discuss society practice concerns. Secretarial minutes were kept and available through the Ontario Jewish Archives. The group was established shortly after the formation by Dorothy Dworkin and the Ezras Noshim Women of the Mount Sinai Hospital in a converted large home on the now-swish Yorkville Avenue.

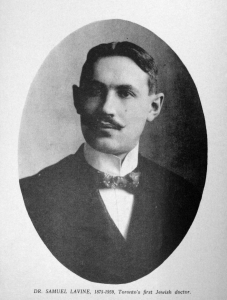

The first Jewish doctor in Toronto was Dr Samuel Lavine,1898 grad of Trinity Medical School just before the establishment of the U of T med school. Lavine made house calls on a bicycle and in 1906 became a society doctor with the Pride of Israel Benefit Society. Discussion at the initial meeting of the Jewish Medical Society covered such matters as raising fees, restricting societies and members per individual doctors, and the reasons a certain society was avoiding their services. The group supported the Mount Sinai Hospital and by 1929 changed its name to the Mount Sinai Clinical Medical Society. With the translocation of the hospital to University Avenue in 1953, service rounds prevailed, and a replacement organization, the Maimonides Society, arose (now long defunct).

The first Jewish doctor in Toronto was Dr Samuel Lavine,1898 grad of Trinity Medical School just before the establishment of the U of T med school. Lavine made house calls on a bicycle and in 1906 became a society doctor with the Pride of Israel Benefit Society. Discussion at the initial meeting of the Jewish Medical Society covered such matters as raising fees, restricting societies and members per individual doctors, and the reasons a certain society was avoiding their services. The group supported the Mount Sinai Hospital and by 1929 changed its name to the Mount Sinai Clinical Medical Society. With the translocation of the hospital to University Avenue in 1953, service rounds prevailed, and a replacement organization, the Maimonides Society, arose (now long defunct).

Society practice was still enmeshed with problems. Doctors felt exploited by the societies’ capitation scheme which reflected the acumen of Society officials’ recognition of the strength of mass buying power. Society patients had issues with service response and value. In 1938, Mr Charles Sanders proposed a Central Medical Bureau (CMB, located at 21 Dundas Square) to simplify payment and collection as well as improving MD availability. This was accepted by all. A brochure was issued listing forty MDs available to all society members and charges were $4 for single and $20 for family. Services not covered in capitation included VD treatment, surgery, obstetrics, IV therapy, anesthesia and pediatric care for infants under six months.

Original Mt Sinai on Yorkville

All did not run smoothly. The Canadian Jewish Congress had set up a societies committee to integrate Eastern European Jews in community affairs. Their secretarial minutes revealed ongoing society issues which earned much discussion with little resolution. Left-wing committee members looked upon society members as “the people,” i.e. the downtrodden proletariat, while doctors were seen as members of the privileged. Little concern was shown for the MD exploited by scandalously low rewards while society members were flourishing in prospering Canada.

Tangential but relevant, the speakers at the 2004 medical graduation banquet were Drs.Cam Grey (3T9), who taught me clinical methods, Henry Barnett (4T4) in the Canadian medical hall of fame, Joan Vale (4T9), all University professors, each of whom emotionally described and condemned the antisemitism they witnessed at medical school.

In 2013 Dr Jack Laidlaw (4T4) presented the case of the much cited Dr Barney Berris (4T4) at the Toronto Medical History Club. A top-ten student, Berris was denied postgrad education at a teaching hospital and obtained internal med education at U. Minnesota. In 1951 he became the first proposed MD of Jewish background for a position at the Toronto General Hospital. Initially rejected by medical staff and board of directors alike, it took the threatened resignation of his proposer, Chief of Medicine Dr Ray Farquarson, to finalize his appointment. Dr Farquarson, the doctor’s doctor, was a person of great virtue whose accomplishments deserve recognition. Referrals to Dr Berris came largely from the society doctors, not his hospital colleagues.

The appearance of low-cost group insurance signaled the end of Society medicine. Society doctors, along with the emergency departments of Toronto General and Sick Children hospitals, had provided adequate low-cost medical care for the Jewish community which prospered with Canada’s growth. Society doctors with maturation and growing self-confidence expanded their purview and also shared in Canada’s beneficience.

Jewish mutual benefit societies in New York and Boston, like those in Toronto, have described doctors who were burdened both with overwork and patient disgruntlement. Toronto’s Society doctors were a pioneer group of family practitioners who obtained a medical education despite quota restrictions. They received little recognition for their work under capitation or their unique position in medical society.

For the immigrant Jewish family they personified decency and uprightness, inspiring many to follow their example; some earned inclusion in the Canadian medical hall of fame. They helped develop Mount Sinai into its current position as a major unit of the U of T Med School and internationally recognized hospital. The first teaching chief of medicine at Mount Sinai was Dr Mitchell Kohan, a family doctor by origin, again a manifestation of Dr Farquarson’s influence. The Society Doctors, by example and conduct, contributed to the dignity and respectability of Toronto’s Jewish community.