From the Canadian Jewish News, May 12, 1972

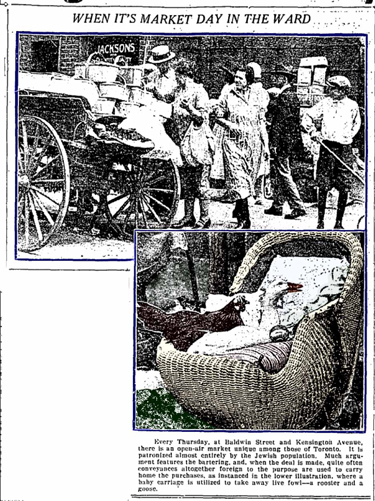

For some time now it has been open season for Toronto’s Spadina Avenue and its off-shoot the Kensington Market in the daily, weekly and periodical press. At one time when The Toronto Star and the late Telegram were both carrying TV and entertainment supplements, one could expect a contribution about every second or third week in either of these publications with the usual photographs of squawking ducks, a grizzly poultry shoichet with bloodied and feathered apron, and a montage of the Victory Burlesque, Shopsy’s and the high-rise garment lofts.

For some time now it has been open season for Toronto’s Spadina Avenue and its off-shoot the Kensington Market in the daily, weekly and periodical press. At one time when The Toronto Star and the late Telegram were both carrying TV and entertainment supplements, one could expect a contribution about every second or third week in either of these publications with the usual photographs of squawking ducks, a grizzly poultry shoichet with bloodied and feathered apron, and a montage of the Victory Burlesque, Shopsy’s and the high-rise garment lofts.

Because of the interest stimulated by all this writing bona-fide shoppers at Perlmutar’s bakery have to fight their way to the counter amidst the throng of curiosity seekers and “tourists.”

Because of the interest stimulated by all this writing bona-fide shoppers at Perlmutar’s bakery have to fight their way to the counter amidst the throng of curiosity seekers and “tourists.”

Magazine editors still haven’t tired of assigning this story. As recent as February of this year, Toronto Life carried a story by Cathy Wismer with the same goal as all the other articles, attributing a by now trite atmosphere of glamour, crime, double-dealing and conspiratorial intrigue to this out-sized artery that runs down Toronto’s sensitive spinal column a mile west of Yonge Street.

Miss Wismer’s article suffers from an overdose of the wide-eyed naivete that seeks colour and exotic thrill at every corner and in every shop window and which goes breathless contemplating the Human Comedy that passes from Old Knox College down to Clarence Square. The older denizen of Spadina who reads it might feel akin to the character in Moliere’s comedy who suddenly is told that all his life, unbeknownst to himself, he has been talking Prose!

Much is made in the familiar style of Ben Hecht and Mark Hellinger of the “pimp and the priest, artist and alcoholic” with suggestions juxtaposed of prostitution rings, razor slashings, street brawls and petty thefts.

Cornerstone of Spadina, according to the researches of Miss Widmer, is the Scott Mission, purveyor of food to the down-and-outers. Surprisingly, she fails to mention a cardinal point about its founder, the late Morris Zeidman — that this ordained Presbyterian clergyman, born in Czenstochow, was a meshumad — a converted Jew. (She does, however, manage to misspell his name consistently as Ziedman.) What is unintentionally amusing is how seriously and straight-faced she reports the glamour of the haberdasher who papers his walls with signed autographs of the “show-biz” greats.

Cornerstone of Spadina, according to the researches of Miss Widmer, is the Scott Mission, purveyor of food to the down-and-outers. Surprisingly, she fails to mention a cardinal point about its founder, the late Morris Zeidman — that this ordained Presbyterian clergyman, born in Czenstochow, was a meshumad — a converted Jew. (She does, however, manage to misspell his name consistently as Ziedman.) What is unintentionally amusing is how seriously and straight-faced she reports the glamour of the haberdasher who papers his walls with signed autographs of the “show-biz” greats.

A few of the features left unmentioned that escaped her attention:

- that the Standard Theatre (now the Victory Burlesque) is the only building in North America — perhaps the world — that was constructed for the purpose of housing a Yiddish theatre

- that the Crescent Grill, as it was called, has as many Damon Runyon types as the drugstore at Dundas and Spadina (which, of course, doesn’t lack them); the same applies even more so (with the addition of the occasional Talmud chochem) to Ladowsky’s United Bakeries

- that the Homestead restaurant in its day was a real centre of the bohemian-intellectual elite

- that the noted anarchist, Emma Goldman, used to lecture at the Labour Lyceum and other Spadina avenue halls (to say nothing of Melech Ravitch, Leivik, Zalman Schneiur, Hayim Greenberg, Zerubovel and the entire galaxy of Jewish political and poetic figures).

Moreover, this list could be expanded indefinitely for the irony is that there is history and colour inscribed in every brick on the Avenue but not in the lurid tones and categories that Miss Wismer paints.

Some day an article will be written on Spadina that will truly tell its story. In the meantime, editors will continue to assign the kind of article that paints the melodrama thick, heavy — and phony. In the meantime, editors, please — don’t overwork the theme in such an underdone way! ♦

© 2012 by the family of the late Ben Kayfetz.