In the year 1839, had you been a traveller along the road from Rzeszov to Cracow, you would have been obliged to show a passport in Podgorze, the suburb of Cracow on the Austrian side of the Vistula (“Weichsel”) River. After submitting to a cursory inspection from Austrian officials, your vehicle would have crossed the river on a bridge supported by floats and entered the ancient capital of Poland. On the Russian Polish side of the line, the police would have required you to complete this printed questionnaire:

In the year 1839, had you been a traveller along the road from Rzeszov to Cracow, you would have been obliged to show a passport in Podgorze, the suburb of Cracow on the Austrian side of the Vistula (“Weichsel”) River. After submitting to a cursory inspection from Austrian officials, your vehicle would have crossed the river on a bridge supported by floats and entered the ancient capital of Poland. On the Russian Polish side of the line, the police would have required you to complete this printed questionnaire:

1. Your name and surname?

2. Your rank, and office, and employment?

3. Your native country, and place of birth?

4. Your age?

5. Your religion?

6. Your condition in life, unmarried, married, widowed?

7. From what place you have last come?

8. How long you propose to remain here?

9. Did you come alone, or had you companions?

10. Had you a passport?

11. Where do you intend to go after leaving this?

Imagine how genealogists would prize these completed questionnaires, if a cache were to surface miraculously in some obscure archives! Alas, it is highly unlikely that any have survived the ravages of 155 years or even that a serious attempt was ever made to preserve them. Fortunately, our knowledge of this questionnaire and of other minute details of Eastern Europe life including rare English language descriptions of Jewish life has been preserved in an account of an 1839 journey written by Protestant missionaries from the Church of Scotland, a copy of which reposes in Toronto’s Robarts Library.

Imagine how genealogists would prize these completed questionnaires, if a cache were to surface miraculously in some obscure archives! Alas, it is highly unlikely that any have survived the ravages of 155 years or even that a serious attempt was ever made to preserve them. Fortunately, our knowledge of this questionnaire and of other minute details of Eastern Europe life including rare English language descriptions of Jewish life has been preserved in an account of an 1839 journey written by Protestant missionaries from the Church of Scotland, a copy of which reposes in Toronto’s Robarts Library.

Published in Philadelphia, Narrative of A Mission of Inquiry to The Jews provides many outstanding descriptions of Jewish communities in Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Holy Land. The travellers’ object was to assess how ripe the Jews were for conversion by observing Jewish sites, living conditions and attitudes. While some might consider the book unkosher, the authors regarded the Jews highly and penned much of special interest to Jewish genealogists.

Departing from London, the deputation moved through France, Italy, Malta and Greece, then sailed to Egypt. The elaborate descriptions of Jewish life in Palestine include this prescient account of the encampment of the wealthy British Zionist, Sir Moses Montefiore, on Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives: “He had fixed a cord round the tents at a little distance, that he might keep himself in quarantine. On the outside of this, a crowd of about twenty or thirty Jews were collected, spreading out their petitions before him. Some were getting money for themselves, some for their friends, some for the purposes of religion. It was an interesting scene, and called up to our minds the events of other days, when Israel were not strangers in their own land.”

The authors devote more than one third of their 555 page work to their sojourns in the Holy Land, but it is their return journey through Cyprus, Constantinople and beyond that genealogical researchers concerned with Eastern European Jewry will find most compelling. Their itinerary threaded through or near a host of Jewish communities, including:

Wallachia & Moldavia: Galatz, Ibraila, Buchares, (Buseo), (Foxshany), (Taotchy), Birlat, Jassy, Kotsin, Waslui, Botouchany, Teshawitz.

Austrian Poland: Soutchava, Seret, Czernowitz, Gertsman, Zalesky, Jaglinsky, Zadcow, Copochinsky, Trembowla, Gulonitsky, Tarnapol, Zalosc, Seretsky, Potkamin, Brody, Sassaw, Zloozow, Zopka, Premyslaw, Lemberg, Grudak, Laskovola, (Bejepee), Jaroslaw, (Zeworsk), (Lanshut), (Rzezow), Zenzow, (Ropsitza), (Veniky), (Pilsno), Tarnow, Bochnia, (Vieliczka), Cracow.

Prussia & Hamburgh: (Breslau), (Zarnow), (Gleiwitz), (Berun), (Nicholai), Oppeln, Prausnitz, Traenberg, (Rawitx), Lizza, Posen, Margonim, Storchnest, Kempen, Inaworclaw, Schlichtingsheim, Rogasin, (Fraustadt), Krotosheim, Kobylin, Glogau, (Klopschen), (Neusaltz), (Lessen), (Frankfort on the Oder), Berlin, Hamburgh.

As they passed through areas of present day Romania, Ukraine, Austria, Poland, Slovakia and Germany, the authors recorded physical descriptions of towns and the surrounding countryside and details of Jewish population statistics, prayer services, synagogues, marriages, funerals, schools, inns, customs and dress. Dozens of simple engravings depict unnamed Jews performing religious customs, Jewish dress, buildings in particular towns, and horse drawn carts and other modes of conveyances. There are even some pictographs from Jewish tombstones and several full tombstone inscriptions, for example that of an impoverished young Italian Jew, Isacco Franchetti, who was buried at the Jewish cemetery in Leghorn in 1832. The narrative even identifies a select handful of Jews by name.

Many passages such as the following sentences about Jassy (Iasi), indicate that Jewish populations in some shtetlach were anything but homogenous.

We entered the shop of a Jewish watchmaker, a pleasant gentle young man from Odessa, who had settled here to escape being taken as a recruit into the Russian army, the ukase having ordered twelve men to be taken out of every hundred, including both Jews and Christians. He told us that there are thirty Jewish families here, who have an old synagogue, which is very small but that eight German families from Vienna are building a new one for themselves, because, few as they are, there is a disunion among them….By this time about a dozen Jews had gathered round, who conducted us to the synagogue. Among them was a mild young man, a Spanish Jew, of a remarkably fine appearance, and very kind to us; but he could not speak any language except Spanish, though he understood a little German. Along with him was a friend, a German Jew, equally interesting and very affable. We were standing at the spot where the new synagogue was building, while the Jewish workmen were sitting down to their midday meal at our side.

Further suggesting the diversity of the Jewish community is the revelation that a city like Jassy, with roughly 20,000 to 25,000 Jews, possessed about 200 synagogues, most of them small. “In one quarter there are twenty, all within the space of a street.” Despite the inconvenience of travel in the early 19th century, some highways were “macadamized” in the British style, affording smoother transport for a brashovanca, fiacre or other wheeled conveyance. Besides undertaking large migrations between states, Jews evidently commuted from town to town on occasion.

Thus we read: “Late at night we arrived at Waslui, and found one Jewish khan [roadside inn] already fully occupied with Jews, on their way to Jassy to keep the day of atonement there.” There is also an account of thousand of Jews flocking to pay homage to a revered rabbi.

For many places visited, the authors provides informative introductory sketches. This is important background information for genealogists who hope to publish histories of Jewish families in localities mentioned. What researcher assembling an account of the history of a family from Czernowitz would choose not to quote the following colourful passage?

Czernowitz is a pleasant town, with streets wide, well aired, and clean. The houses are generally two or three stories high, and there are barracks and other public buildings…. There are 3,000 Jews here, with eight synagogues, only three of which are large. These three we visited, being all under the roof of one large edifice. The congregation were engaged in worship when we entered (and) … a group soon gathered round each of us at different parts of the synagogue. On saying to those around, “We have been at Jerusalem,” they were immediately interested, and asked, “Are the Jews there like the Jews here?”

Genealogists may also find the various cemetery descriptions of interest. I do not know the present condition of any Jewish cemeteries in Tarnapol, but having read this book, I now know that a large Jewish burying place once stood near the entrance to town. “It is covered with upright gravestones, some of them 200 years old, having inscriptions generally in good preservation, and some elegant monuments over the Rabbis.” Those who, like myself, have studiously pored over 19th century Polish Jewish death records may find illuminating a contemporaneous account of a Jewish funeral; there are several in the book. Some anecdotes, such as the following account of a cemetery superstition, might more rightly belong in a Yizkorbuk.

We were shown the grave of a Jewess, who died 200 years ago, named Galla, the daughter of a rabbi, who is said to have lately wrought miracles on diseased persons who prayed at her grave. Some time ago, she appeared in a dream to several people in town, and told them that she had got this power. Many went to the place, and, according to the story of our guide, were cured. A heap of twigs lay piled up several feet near her gravestone, each one put there by the hand of some grateful Jew or Jewess who had reaped the benefit of a visit to her grave. Our guide assured us that his grandmother had been completely cured of a desperate disease, by coming to pray beside this grave.

Myriad details provide a composite sketch of Jewish life. In Zalosc, pictures of the famous rabbi, Landau, adorn most Jewish houses. In Potkamin, “the shomesh or ‘beadle’ was in the act of going round the village, knocking loudly at the door of every Jewish house, to give warning that the hour for worship in the synagogue had arrived. In Brody, where the travelers lodged in a respectable inn kept by a German Jew, they were awakened at an early hour in a most unceremonious way, by “a series of officious Jewish hawkers coming to our chamber, eager to dispose of their goods. First of all the door was pushed open, then a fur cap and long beard thrust in, while a voice demanded, in German, if we needed knives or combs. No sooner was this visitor gone, than another similar head was thrust in, and a voice asked, if we wished to buy soap. This singular kind of annoyance was repeated by eight similar visitors before we were fully dressed, and we were obliged at last in self defence to lock the chamber door.”

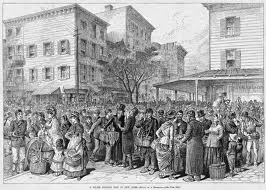

By necessity, Jewish genealogists in the post Holocaust era are relegated to sifting through the bones and ashes of a vanquished Jewish world. Accounts of what once was help us recall the vibrancy of the life that was stamped out. Brody, with its 150 synagogues, “seemed wholly a Jewish city; and the few Gentiles who appeared here and there were quite lost in the crowd of Jews.” Indeed, the authors assert that “the appearance of the population was certainly the most singular we had witnessed.”

Jewish boys and girls were playing in the streets; and Jewish maid servants carrying messages; Jewish women were the only females to be seen at the doors and windows; and Jewish merchants filled the market place. The high fur caps of the men, the rich head dress of the women, and the small round velvet caps of the boys, met the eye on every side as we wandered from street to street. Jewish ladies were leaning over balconies, and poor old Jewesses were sitting at stalls selling fruit. In passing through the streets, if we happened to turn the head for a moment toward a shop, some Jew would rush out immediately and assail us with importunate invitations to come and buy. In the bazaar, Jews were selling skins, making shoes, and offering earthenware for sale; and the sign boards of plumbers, masons, painters, and butchers, all bore Jewish names. In the fish market, the same kind of wrangling and squabbling heard in our own markets was carried on by Jewesses, buying and selling. Jewesses also presided at the flesh and poultry market, and in a plentifully stored green market. Near these were shambles for torn meat, to be sold only to Gentiles, Jews being forbidden in the law to eat “any flesh that is torn of beasts.”

Although somewhat sociological and anthropological in tone, these observances by proselytizing Gentiles, outsiders to our culture, are greatly illuminating. It’s clear that the authors could not help but see the Jews as a sorrowful anachronism of history, justly forsaken by their outmoded God. But their attitude towards the Jews is generally benign and they managed to capture quintessential elements of a diverse, complex, thriving culture. Genealogists seeking insights into specific localities may find them here. The book also helps us realize how lucky we are, now that debilitating sea voyages, horse carts, bumpy mud roads and week long quarantines are no longer requisite elements of travel.

My biggest lament in reading this book is that the authors did not swerve into my own ancestral region in the triangle roughly defined by the cities of Lodz, Kalisz and Konin. Having found and translated hundreds of birth, marriage and death documents pertaining to my own Glicensztejn (Glicenstein), Hahn, Ziegel and Kamorow lineages some insinuating dates as early as 1754 I would have given a great deal to read an account of their adventures or misadventures with a Jewish baker, haberdasher, artisan, tailor or faktor who might have been my ancestor or relative. I’ve searched in vain for 19th century English language accounts of travels through my ancestral region. See the brief bibliographic review below for other travellers’ descriptions involving Jews in Eastern Europe and Russia in the 19th century. ♦

© 1997

Other rare 19th century travelogues with references to the Jews:

- Travels in Russia, the Krimea, the Caucausus, and Georgia, by Robert Lyall, M.D., F.L.S. Two volumes, published for T. Cadell, in The Strand, London; and W. Blackwood, Edinburgh, 1825. Discusses Jews in Zvenigorodka and other regions near Kiev (p.3 4); refers to article about Jewish agriculture in Journal of the Agricultural Society of Moscow, No. IV, 1822 (p.4); complains of Jewish monopolies (p.120 121); dispute with Jew over horses (p.132); describes village of Kholovinska (p.132 133); encounter with Jewish driver (p.148); Karaite Jews in Tchufut Kale, p.266 9. Tone of all references is anti semitic.

- Russia: or, Miscellaneous Observations on the Past and Present State of That Country and Its Inhabitants, Compiled from Notes Made on the Spot, by Robert Pinkerton, D.D. Published by Seeley & Sons, & Hatchard & Son, London & Picadilly, 1833. Jews of Witepsk (p.67); in Mogileff (p.82); discussion with Jewish postmaster (p.86 7); Jewish hospital (p.90); Minsk (p.91); dress (p.96 7); on Polish Jews (p.98 103); Wilna (p.102ff); Karaite Jews in Troki (p.107 9); in Covna & Rossiena (p.111); in Telsh (p.118).

- Travels in Greece and Russia, with an Excursion to Crete, by Bayard Taylor. G.P. Putnam, New York, 1859. Contains chapters on Cracow, Warsaw, Central Russia, Moscow & St. Petersburg. Many descriptions of landscapes (i.e. along Dnieper River and in Bobruisk) as well as several derogatory passages about Jews.

- Russian Life in Town and Country, by Francis H.E. Palmer. G.P. Putnam, New York, 1901. Contains two interesting, albeit general, chapters, “Jewish Town Life” and “The Jewish Trader,” plus four evocative photographs.

- Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, Comprising their Life and Work as Recorded in their Diaries from 1812 to 1883. Ed: Dr. Louis Loewe. 2 vols. Griffith Farran Okeden and Welsh, London, 1890. Descriptions of their travels to Palestine, Russia, Wilna, Kowno, Warsaw, Krakau, Posen, Berlin, Frankfort, Morocco, Hungary, etc. ♦ — B.G.