Sixty Years’ Changes, As Hotelman Has Seen Them — The Queen’s Has Been “An Institution” of Toronto, Like the Parliament Buildings or St. James’ Cathedral — Glimpses of ‘60s & ‘70s — View of Bay Fetched Topnotch Price for Rooms — Nickel-plated Self-feeder Supplied Luxury of Heating — Tin Bath When Asked — First Phone and First Elevator

By Mary Dawson Snider

From The Toronto Telegram, May 3, 1924

Bright as the new silver sixpence he brought from his cottage home in Killaloe was the little Irish lad of nine, who landed with his parents in London, Ontario from County Clare away back in 1855.

Bright as the new silver sixpence he brought from his cottage home in Killaloe was the little Irish lad of nine, who landed with his parents in London, Ontario from County Clare away back in 1855.

Bright as guinea gold he is today, though 78 years of age.

His priceless heritage, abounding health and the early training of industrious, upright parents, the little Irish lad has been for more than half a century one of Toronto’s most widely known and best liked citizens.

He is Henry Winnett, owner and proprietor of the Queen’s Hotel.

Sixty years ago, when a boy of eighteen, he became clerk of the Queen’s — then Toronto’s most fashionable hotel. Even the big American House, at the north-east corner of Front and Yonge streets, could not compete with the Queen’s in aristocratic favor, and the popular Rossin House, at the south-east corner of King and York streets, had been raged by fire two years before that.

Comforts of a High-Price Hotel of the Half a Century Ago

“It was a high-priced hotel,” said ‘Tony’ Gilchrist, the Queen’s oldest employee, when questioned. “A dollar and a half, two dollars and even three dollars a day was charged for room and board, and people clamored for the front rooms at the highest price. All wanted windows with the beautiful view of the bay and the Island we had then. We were right on the waterfront, you know, with Jaques and Hay’s furniture factory a little further east, the only high building between us and the shore.”

‘Tony,’ as everybody affectionately calls the handsome old man who for fifty-nine years was night watchman at the Queen’s has a fund of reminiscences of earlier days.

In 1868, a year before Mr. Winnett came to Toronto, he was employed as night clerk and watchman by Capt. Thomas Dick, the hotel’s original owner.

He recalls the two year that Mark Irish was partner with Thomas McGaw in the Queen’s before the former rented the Rossin House in 1871.

Retained by Messrs. McGaw and Winnett when they resumed the proprietorship of the Queens in 1974, he stayed faithfully at his post until two years ago when ill health forced him from it.

“When Mr. Winnett took hold,” said Tony, “a glowing self feeder, all nickel plate and izing-glass, was the first thing you saw on a winter’s night when you came in. That stove had to heat the rotunda and the office.

“In the upper halls were round coal stoves, each of them filled three times a night. Every bedroom had a grate, but fires were only lighted in them on request. Two men were kept to do nothing but light fires.

“There was no such thing as a room with bath, but we provided a tin bath when it was asked for.

“On cold nights every jug on every washstand in the house had to be emptied or the water would freeze and the jug split.

“There wasn’t a double window in the place. Nobody had heard of them.

“I guess we had the first pipeless furnace. It only heated the dining room but we thought our hotel had something wonderful when the big stove that stood in the centre of the dining room was busted and a furnace put in the cellar just beneath where the stove stood.

“We had running water at the Queen’s, but most people depended on wells and cisterns in their own yards. Many a time when these have gone dry I’ve seen puncheons of water carted through the streets to be sold by their enterprising drivers at one cent a pail.

“The reservoir then was away out at the northeast corner of Huron and St. Patrick and the finest residences in the city were on Wellington west, quite near us.”

The Queen’s Had First Phone, First Elevator, Fluid Lamps and Free Busses

The Irish lad Winnett was quick on the up-take. All through his business career he has been swift to apply his ready appreciation of inventions. The Queen’s had Toronto’s first business telephone. It also was probably the first hotel in Canada to install an elevator. John Fensom and Henry Winnett took a trip to New York in 1875 to see how the ‘new contrivance’ worked and how it was constructed. Mr. Winnett’s eyes twinkle as he says, “We came home and had Jaques and Hay’s, whose furniture factory was just down Front street, built the stage for it.”

The Irish lad Winnett was quick on the up-take. All through his business career he has been swift to apply his ready appreciation of inventions. The Queen’s had Toronto’s first business telephone. It also was probably the first hotel in Canada to install an elevator. John Fensom and Henry Winnett took a trip to New York in 1875 to see how the ‘new contrivance’ worked and how it was constructed. Mr. Winnett’s eyes twinkle as he says, “We came home and had Jaques and Hay’s, whose furniture factory was just down Front street, built the stage for it.”

That was nearly have a century ago. Cabinet work was well done then. The original elevator cage is still in use. Its new lining of fine wood is in keeping with the rare old wainscotting of the staircase which dates back to 1828, when Capt. Dick built the four dwelling houses that formed the nucleus of the Queen’s Hotel.

Supposed to arrive at midnight the old Grand Trunk in Mr. Winnett’s early Toronto days was “due any time it got here.” It was usually from two to seven hours behind time.

A few of the rooms at the Queen’s then were lighted by gas, but the majority of the two or three score travellers — arriving from Montreal in the night trooped off down the long corridors, led by lads who with their flaring fluid lamps or flickering lamps of oil, looked like link boys of an earlier age.

“Fluid lamps,” explained Mr. Gilchrist, “were handy little thing with no chimneys. They were just about the size of a small glass ink bottle.”

“For a long time free busses met all trains. The Great Western, which came from the Falls, used the west end of the Grand Trunk platform at Simcoe street before they built for themselves at the foot of Yonge street. I remember when they drove spikes into the soft mud there for the foundation of the old Great Western Station, which is now the fruit market at the west side of the foot of Yonge street. Before that there was no covered entrance from trains, and all stations were clapboarded. The Northern from Collingwood at first came in near the Queen’s Wharf on the west side of Brock street. Later their station was on the bay front, just behind the old City Hall and Lower Market.

“In winter we put the busses on bobs. In summer Capt. Dick used to grow oats for his horses on the lot at the northeast corner of York and Front. That field, for many years was the circus grounds. Circuses came to town by wagon then, travelling Dundas street, Yonge street or the Kingston road.”

Saw Soldier Sons Go Forth and Welcomed Lions of the Hour — Half a Century a Front Bench Spectator of the Big Things in Toronto’s Life

Innumerable are the tales Mr. Winnett could tell of Toronto’s rejoicings and her sorrowings in the last sixty years. The Queen’s is at the city’s portals. Past the hotel’s doors have tramped Toronto’s heroic men, the victors of sport, the heroes of war. To the tunes of Tipperary, Upon the Heights of Queenston, The Girl I Left Behind Me, and the inspiring strains of Rule Brittania, thousands of them have gaily marched away, their hearts much lighter than their knapsacks, a song on their lips, their lives in their hands.

The Fenian raid stands out vividly in Mr. Winnett’s memory. Every guest in the hotel was out oat half past six the morning of the first of June, 1866, when the Queen’s Own passed. From the windows they could see them embark and steam out for St. Catharines on the “City of Toronto.”

Fighting at Ridgeway started Saturday morning, June 2nd.

Sunday morning an appeal was made in Toronto churches for food. Commissariat arrangements had been too hurried to be complete. It was said the volunteers and regulars were starving.

Toronto’s Sabbath quiet was that day changed to made racing of bakers’ carts and conveyances of every kind, hurrying to and from Yonge street wharf. The “City of Toronto” left at three in the afternoon loaded with bread and crackers and cheese, tobacco and beer and biscuits and many a hurriedly made batch of buns and a good wife’s store of poundcake and of cookies for “the boys.”

When the steamer returned that Sunday night, bringing home the dead and wounded, there was a solemn, never-to-be-forgotten tolling of all the church and fire bells in the city.

In those days travellers who reached Toronto at the end of the week had to stay in Toronto. There were no Sunday trains, boats or street cars.

“I used to cut across lots to the Post Office on Toronto street,” said Mr. Winnett. “Except the Queen’s there was not a building on the north side of Front street from York street till you came to Wetherington’s stoneyard at the corner of Bay street.”

“Where the new Union Station is built Lorne street ran south from Front street, directly opposite the Queen’s. On the east corner of Lorne and Front was John Clement’s door and sash factory. Jaques and Jay’s factory was east of that, in front of the hotel was a row of fine chestnut trees and across the street at the west corner of Lorne street, a grove of trees where we had a flagpole and ran up a flag every morning.”

It was up Lorne st., named in their honour, that the Princess Louise and the Marquis of Lorne came in 1879, a crimson carpet spread for them there, stretching from the station to the Queen’s Hotel, and a phalanx of children on platforms at either side of the sawdust-covered roadway shouting their little throats hoarse in carols of welcome. On their second visit to Toronto they were guests at the Queen’s Hotel. The royal coat-of-arms still adorns the suite they occupied and the private stairway used by them gives access to the dining room.

That royal suite has had many occupants of note, including Lord and Lady Dufferin, the Aberdeen; in fact, most of the Governor Generals of Canada, Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, ex-President Taft and Canada’s first Premier, Sir John A. Macdonald.

History has been made in the Red Parlour of this suite. The story goes that it was here John A. Macdonald consummated his plans for confederating the four provinces into the Dominion of Canada, and that here, also, he framed his famous National Policy.

In the days of the American Civil War, there were always twenty-five or thirty expatriated southerners making their home at the Queen’s. Sleighriding, a novelty to them, was their chief joy. Many a merry party they gave with cowbells tied to the tongues of their sleighs and harness jingling with sleighbells. After the ride there was always a supper and dance at the Queen’s, for the place was, as it is now, named for its good food. Coloured waiters then always did the serving. Slaves had not at that time been emancipated by the United States.

Canada at that time was the only land of the free on the North American continent.

So numerous were Toronto’s coloured folk in the ‘70s and ‘80s that in the reception to the Marquis of Lorne, it is recorded, “the coloured band from the Ward came marching down Bay street.”

Christmas dinner at the Queen’s was for years like a jolly family party. A long table, with mine host at the head of it, ran the length of the dining room, and champagne, with which the toasts were drunk, was provided by the proprietor.

Charged now with this prodigality, he counters by saying, “At $25 a case it wasn’t such a luxury then.”

One of the watchman’s duties in the early days of the Queen’s was taking the letters to the post office and bringing back the mail. “At that time,” says ‘Tony’ Gilchrist, “the south-east corner of Toronto and Adelaide was the only vacant lot in that vicinity. There they used to crack stones for the roads. Later letter boxes on short iron stands were put on the streets and a man with a big bag walked from box to box collecting them.

“I remember when Hanlan came home as world’s champion oarsman in 1879; the crush in front o the Queen’s was so great they knocked down the letter box, post and all. “

Like the Phoenix or the Salamander of the Burning Bush, the Grand Old Hotel Has Always Successfully Defied the Flames

“We got a great scare the night of August 3, 1885, when the Grape Sugar Refinery at the foot of Frederick st. took fire about midnight and burned everything along the waterfront right to Yonge st.

“We got a great scare the night of August 3, 1885, when the Grape Sugar Refinery at the foot of Frederick st. took fire about midnight and burned everything along the waterfront right to Yonge st.

“Steamers, yachts, elevators, icehouses, boathouses, all went up in smoke. Bailey’s coal yard at Milloy’s Wharf was the last to go. It burned for days.

“That was the week the boys came home from fighting the Riel Rebellion.

“Ex-Mayor Manning was staying at the Queen’s then. I remember his saying to me, ‘Call all the guests, Tony. We don’t know where this fire will stop.’

“But our slate roof save us. Only the shingles on our ice-house caught.

“All hotels and many private houses stored their own ice in those days.

“We had a closer call in the great fire of April, 1904. Everything east of us beyond our garden was completely gutted, and only Mr. Winnett’s presence of mind saved the Queen’s. He had the staff and volunteers working in relays. We stripped the beds of double blankets, soaked these in the bath tubs and hung them out of the windows. The heat nearly shrivelled us as we tore down the long lace curtains and hung out our wet blankets, jamming them into place with the upper sash of the window so that they covered glass and framework. You don’t know how hot a steaming blanket is till you handle it. We kept changing and soaking those blankets until the brigade of Hamilton firemen arrived and took us out of purgatory. Their hose stopped the westward progress of the fire.”

Even as late as twenty years ago, all the windows of the Queen’s were equipped with picturesque green shutters. For weeks after the holocaust of 1904, workmen were kept busy scraping these. The heat had been so intense they were blistered as a toad’s back. Original hinges for the shutters, put up seventy-five years ago, are still on the window casements.

A Magnate of Magnificent Ideas and Modest Mien

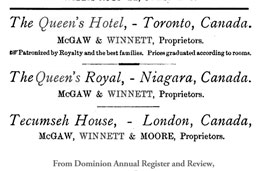

Unlike the majority of successful men, Mr. Winnett shuns publicity. You would never learn from him that he now owns not only the Queen’s Hotel, Toronto, but the Tecumseh House , the big hotel of London, where as a lad he learned the ABC’s of hotel management.

He treasures, but rarely shows, a present given him by England’s kind.

When King George, at that time Duke of Cornwall and York, was leaving the Queen’s Royal, Niagara-in-the-Lake’s delightful annex of the Queen’s Hotel, he presented Mr. Winnett with a diamond-studded scarf pin saying, “Just our own flower — the rose of York,” and the Duchess of York gave Mrs. Winnett a diamond brooch.

Modest though he is, Mr. Winnett admits he has always had big ideas. He tells how when the Metropolitan Church, capable of seating 3,000 people, was being built here early in the ‘70s, he used to say to all who boasted of it, “You should go to Ireland if you want to see a big church!”

Visiting the land of his birth in 1later years, he took Mrs. Winnett to see the huge Anglican Cathedral at Killaloe where as a child he had attended service.

At this point in the story his eyes twinkle and he chuckles:

“As we walked up the tiny aisle my wife squeezed my arm and whispered:

“’Is THIS the big church?’”

His ideas are still big. His plans for the future of the Queens are great or greater than they have ever been. At 78 he waits the building of the viaduct. With the throwing open at his doors of the portals of the new Union Station he will see the realization of the biggest of his long-cherished dreams, for the hotel that for sixty years he has made homelike to thousands from all quarters of the earth. ♦

* * *

More about the Queen’s Hotel

“The Queen’s Hotel is known to every visitor of prominence to the flourishing city of Toronto,” noted C. Pelham Mulvany in his 1884 book, Toronto Past and Present. He cited the hotel’s “capacious, airy, well-appointed apartments” among the reasons it was “among the noted hotels of the North American continent.”

“The Queen’s Hotel is known to every visitor of prominence to the flourishing city of Toronto,” noted C. Pelham Mulvany in his 1884 book, Toronto Past and Present. He cited the hotel’s “capacious, airy, well-appointed apartments” among the reasons it was “among the noted hotels of the North American continent.”

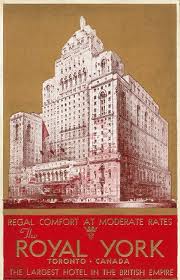

Henry Winnett became sole proprietor after buying his partner Thomas McGaw’s share upon McGaw’s death in 1901, and continued in that position until his own death in 1925. In February 1927 CPR purchased the hotel for $1 million and closed it down, opening its replacement, the Royal York Hotel, on the site on June 11, 1929. With its 28 floors and 1048 rooms, the Royal York was the largest hotel and the tallest building in the British Empire. ♦

* * *

More about the Winnett Family

Henry Winnett was born January 17, 1846 in Killaloe, Ireland. His parents were Henry Winnett (1814-1903) and Ellen North Winnett.

One story about Henry which should be worked in prior to his partnership in 1874, appeared in the London Advertiser July 9, 1927, page 4:

Henry Winnett, named for his father Henry Winnett, the boilermaker, died a millionaire, and one of the best known hotelmen on the continent. He started life as a bellboy in the Techumseh (sic) House, became clerk and bookkeeper there, and one day made a large amount of money by buying up all the bills of a bank that had failed, at very low prices. They were afterwards redeemed at par, and for a few hundred dollars young Winnett found himself in possession of about $15,000. Later he went to Toronto, became associated with the Queens Hotel, and subsequently bought it. He also bought the Tecumseh House here and his estate still owns it. Mr. Winnett also had a large hotel at Niagara Falls. ♦

Source: http://members.shaw.ca/davesfamily/winnett_add.html (May 2012)

* * *

Comments

Sir:

I have read the article on Henry Winnett and the Queens. I am Henry’s GGGrandson, Edward Winnett T– (Ted). It is fun for me to see stories on the family.

I have read the article on Henry Winnett and the Queens. I am Henry’s GGGrandson, Edward Winnett T– (Ted). It is fun for me to see stories on the family.

In the story there is a reference to a John Clement. He was Henry’s father-in-law, his wife Jessie Winnett’s father.

They owned The Queens Royal Hotel in Niagara on the Lake. (Pic) It’s not there anymore there is a park where it use to be and the Tecumseh house in London Funnly enough I have the lobby Clock from the Queens Hotel Toronto.

Thanks for the entertainment. All the best for the New Year.

T.T., Toronto (Jan 2013)