From the Toronto Star weekly October 4, 1913

Some men who began with the bag over their shoulders now worth around $1 million — Old iron sold to the foundaries to be recast — Bones made into glue, fertilizers, and used in refining sugar – Paper and rags go to the Mills — Nothing is wasted – Competition is very keen today

◊ “My grandfather was just a pedlar” — how many times have we heard this disparaging comment about a profession that, as this article reveals, was sometimes the springboard to amazing success in business? Provided he had brains as well as sufficient capital to invest, the pedlar could build himself up over time into a wealthy man. As this article shows, the junk business was a huge and highly competitive concern in the Toronto of a century ago. –B.G.

◊ “My grandfather was just a pedlar” — how many times have we heard this disparaging comment about a profession that, as this article reveals, was sometimes the springboard to amazing success in business? Provided he had brains as well as sufficient capital to invest, the pedlar could build himself up over time into a wealthy man. As this article shows, the junk business was a huge and highly competitive concern in the Toronto of a century ago. –B.G.

“Rags! Bones! Bottles!”

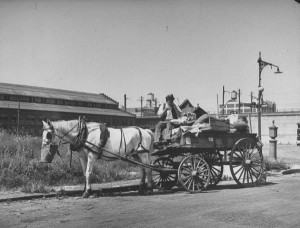

When we hear this plaintive, and somewhat unmusical, cry in the Toronto streets, do we ever think of the magnitude of the aggressive business whose cheap war cry it is? The leaking capital, or the bit of lead foil from empty tea packets, which you sell for a few cents to the bearded stranger whose bleating notifies you of his approach, are items in transactions which involve a great many cents and a great many dollars in the course of the year.

The bearded stranger himself is but one step – the lowest – in the colossal junk ladder. For the dealers in junk in Toronto are divided into three classes. First, there is the peddler, who goes from door to door. He needs little enough capital to start in his small way – “a dollar and the bag are enough to commence with,” the Star Weekly was informed by more than one member of the profession. There are over two hundred of these door to door “rag and bone” men in Toronto, and the great majority are Jews, though there are some Christians among them.

Most of them eke out a living at the game, and even save at it. For they will save where less thrifty folk would starve. But as soon as they have scrape together a few dollars they go into the real estate business – still, of course, keeping on with the junk as well — no matter in how small a way. For in this lowest grade of the junk business, there are no large fortunes to be made. And ninety per cent of the Jewish people in Toronto, said one of them to the Star Weekly, go into the real estate business in one form or another.

The Higher Grades

The successful peddler becomes the junk retailer. Of these there are probably not a couple of dozen in the city. They buy from the peddlers and sometimes from large concerns. And they sell to the wholesalers. Above the retailers again are the wholesalers, and their transactions are in the thousands.

“I often,” said one of the largest of the last mentioned to the Star Weekly, “engage in ten-thousand (dollar) deals – that is quite an ordinary occurrence. And I have sold as much as twenty-five (thousand) dollars’ worth of stuff at one time. Yes, I started with very little, and worked my way up. The head of one of the biggest metal houses in the city started as a peddler with a pushcart, then he became a retailer, and now he is where he is today, worth an amount it would be difficult to estimate.”

The most striking thing about the junk business is its wide scope. It includes literally everything from the buying of a tin tack to the purchase of the junk into which the process of dismantling converts a Lieutenant Governor’s residence.

“The business,” said the wholesaler before quoted, “is one that wants brains – plenty of brains, and also plenty of money. It may seem difficult for you to realize that a lot of discarded and badly battered pieces of iron rods can be the subject of large pecuniary operations. But such is the case.

Ten Millions a Year

The junk operations in Toronto are of the extent of at least ten million dollars a year. That is a very low estimate. And it would hardly include the amount which the handling of pig iron totals. The business is one which requires brains for many reasons. To you one pile of scrap iron looks very much like another. But not so with the junk dealer. This knowledge enables him to pick out each article and value it correctly. In addition, he knows how to turn it into the most money possible for an article of its particular kind.

“But the business, on a large scale, calls for plenty of money as well as plenty of brains. We have to handle the whole pile of money for a very small margin of profit. The other day I bought a carload of rubbers, and gave $3,000 for it. On resale I made a profit of less than $100. And that is about our average ratio of expenditure and profits.

“Moreover, the business calls for good judgment. For at least as far as that part which deals in metals is concerned, it is, to a great extent, something of a speculation. Metals fluctuate in value, and sometimes you’re liable to find yourself with a large stock on hand for which you have no sale except at a very great loss. Look at that lot of red iron out there,” pointing to a huge heap in his yard. “The market in red iron happens to be very dull just now, and I have got to hold that lot. In fact, I have held it for four or five years, and there are many thousands of dollars locked up in it.”

Where It Goes

Romance does not hover around the junkyard. None the less it is a place which gives the observer occasion for not a little reflection. There are hundreds of tons of material going into some of the finest buildings that are being erected in Toronto today which, only a few months ago, were piled up in ugly and seemingly useless heaps, in the junkyards of the city. And prior to that, they have been salvaged from some dilapidated old structure – “just junk,” as the ordinary passerby would have said.

The big junk dealers of the city are the buyers of carload lots. They occupy the position of clearing house between the great mills and (smaller) plants, or the large contractors who buy rails of iron in huge quantities and the little collectors. “What becomes of all the junk?” asked the Star Weekly of another leader in the local trade.

“Nothing is wasted,” he replied. “Cast iron is sold to the foundries, and new castings are made of it. Other kinds of iron are made into bar iron in the mills. Bones are sent to refineries, and from them are made glass and fertilizers. They are even used in refining sugar. Paper and rags go to the mills, and from their new materials are made. Bottles go back to the breweries, and are used as new bottles. The junk business is a regular merry-go-round of a trade.

Bigger in States

“Business in Toronto is not a bad one, but it does not reach the same dimensions as in the large cities in the United States. In Canada, the railroads use such a lot themselves in their own foundries. In the States there are dealers who are not afraid of a quarter of a million deals. But here we do not touch a figure like that. For the most part, it is little by little, comparatively speaking, that we make our profits. Still, there are some junk dealers here who started with little or nothing, and are now worth something around one million dollars, but the accumulation of their money has been a matter of a long time.

“Another circumstance, in connection with the junk trade, is that competition today in that trade in Toronto is far keener than it was twenty years ago. Consequently, profits are cut to a much greater extent.”