From North Toronto Tales, 1948

by Lyman B Jackes

There is no section of the present City of Toronto which can claim the historical background that is the heritage of North Toronto. Writers for many years have been prone to stress the fallacy that communal life in these parts commenced in the vicinity of the old fort at the foot of Bathurst Street and at the foot of what is now Parliament and Berkeley Streets.

There is no section of the present City of Toronto which can claim the historical background that is the heritage of North Toronto. Writers for many years have been prone to stress the fallacy that communal life in these parts commenced in the vicinity of the old fort at the foot of Bathurst Street and at the foot of what is now Parliament and Berkeley Streets.

This assumption is wrong. North Toronto can lay claim to having supported the first community centre in the vicinity of present day Toronto. It was a centre that goes back to at least the time of Christopher Columbus. Yes. You have guessed it. It was a settlement of Indians.

However, this was no fly by night settlement. It was a well-organized and extensive community that had its centre in an artesian spring of pure water. The spring flowed where the modern water tower rears its head on Roselawn Avenue, just to the west of Avenue Road. This artesian spring formed the centre of the community. The great tribal huts were on the site of the present Allenby Public School. The steep hills that are the bain of modern motorists in the vicinity are not natural. They were man-made and are the remains of mounds where corn and other stocks of food were stored.

However, this was no fly by night settlement. It was a well-organized and extensive community that had its centre in an artesian spring of pure water. The spring flowed where the modern water tower rears its head on Roselawn Avenue, just to the west of Avenue Road. This artesian spring formed the centre of the community. The great tribal huts were on the site of the present Allenby Public School. The steep hills that are the bain of modern motorists in the vicinity are not natural. They were man-made and are the remains of mounds where corn and other stocks of food were stored.

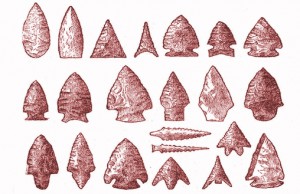

The extent of this great Huron village can be gauged by the archaeological remains. It is true that the cream of the specimens have been recovered and removed. It is not uncommon for the amateur gardener to uncover flint arrowheads and other specimens. In many cases these are not recognized as manmade.

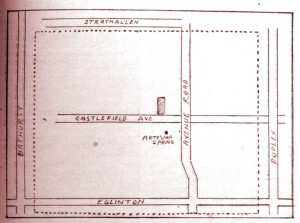

Location of great Huron village that once thrived in north Toronto. The ancient pallisade walls are shown as dotted lines.

In the spring of the years 1947 the writer picked up a very good specimen of an axe head which had been tossed out on the pavement on Castlefield Avenue. Someone, digging in the garden, had brought it to light. They may have been aroused by its shape and hewn edge and expressed some curiosity concerning the item. But that was all. It was tossed out with other garden refuse. Some very fine specimens of flint arrowheads were recovered by the writer but they were poor specimens compared to the wonderful collection that came from Castlefield and which was available to the writer when he was a boy. These specimens included pottery of various ages. Pipes, arrowheads and various stone and clay utensils. There were also some very wonderful flint axe heads. Some of these items were decorated and others were of plain manufacture. Style, shape and finish suggested that they were manufactured over a wide space of time.

Early writers of the Toronto area make no mention of this great Indian settlement. When the French came to Humber Bay in 1749 and erected Fort Toronto such documents as they issued make no mention of a great Huron settlement in the vicinity. The Indian trade routes were down the Humber from the Georgian Bay district. That is why the French erected their fort. They wanted to capture that trade before it crossed the lake to the English at Oswego.

Mrs. Simcoe, in her diary that was written between the years 1792 and 1796 makes no mention of any great Indian settlement in the Toronto area. What happened to it?

When the excavations for the Allenby school were in progress a partial answer was given to that question. A great number of human remains were found. They were not in the usual Huron burial fashion. Many fragments of charcoal were found and the evidence strongly suggested that the great number of Indians who had died on this spot had been killed while an extensive bark structure had come tumbling down in flames upon them.

When the excavations for the Allenby school were in progress a partial answer was given to that question. A great number of human remains were found. They were not in the usual Huron burial fashion. Many fragments of charcoal were found and the evidence strongly suggested that the great number of Indians who had died on this spot had been killed while an extensive bark structure had come tumbling down in flames upon them.

There is some evidence that the Iroquois fell upon this peaceful settlement when they were on their way to Fort Ste. Marie in the summer of the year 1649. It is possible that the Hurons were taken by surprise and as they defended their village foot by foot the various bands of defenders finally collected about the great community huts in the centre of the place. There the final slaughter took place.

Archaeology along can supply the answer to what happened after the first great settlement was wiped out. The first explorers of the area are all definite on one point. There were two distinct types of trees. An area roughly bounded by Eglinton Avenue on the south, Duplex Avenue on the east and Bathurst Street on the west and Strathallen Boulevard on the north gave indications that the trees in that area were of a much more recent growth than those in the surrounding forest. That suggests that the Hurons had cleared the area and enclosed it with a palisade. Some of the area was cultivated and the remainder was occupied by the communal and residential huts of the Indians.

If this great village was wiped out by the bloodthirsty Iroquois, as strong evidence indicates, it is also possible that for a century or more that roving bands of Hurons returned to the site to take advantage of the manufacturing facilities that the district afforded and to secure food that had been stored. The Hurons had developed a method of roasting their corn and grain and burying it in charcoal. This preserved its edible qualities for a long time. As late as the year 1880 an exploring party on the site uncovered one such cache of food and the corn was still edible.

In the year 1880 the provincial government instructed its archivist to visit the site of these extensive Indian remains. A report was published and is now stored in the government library at the Parliament Buildings in Queen’s Park. The report is headed “A Study of Indian Remains on the Jackes Estate, Township of York, near Toronto.”

The report states, in part, that Mr. Baldwin Jackes had drawn attention to the great number of relics that had been uncovered by the plough in the hilly section of the farm toward the rear of Castlefield.

Mr. Baldwin Jackes was one of the younger sons of Franklin Jackes and in the year 1880 operated a drug store on the east side of Yonge Street just above Gould Street.

The provincial archivist, with a party of assistants, visited the remains and made a very extensive study of the ground and locality. The district referred to is the area of the water tower on Roselawn Avenue, just to the west of Avenue Road. In 1880, of course, there was no water tower there but the artesian spring still gushed out its supply of cold, fresh water.

The report that was prepared for the Minister of Education at that time lays stress upon the fact that the evidence is very strong in support of the claim that a very extensive Huron Indian village once existed on the site. The trees in the neighborhood would suggest that they were at least two centuries old at that time. The timber farther removed from the site was of a much older growth. This would suggest that the settlement had suddenly ceased to exist some time during the seventeenth century. The vast amount of material brought to light in the upper layers of the earth suggested that some sudden catastrophe had overtaken the settlement.

The report also lays stress upon the possibility that after the first great settlement had vanished bands of Indians returned to the locality over many years to take advantage of the clay and other materials of the district for the manufacture of cooking utensils and other pottery items. These items which were evidently made during a later period were of inferior manufacture to the great mass of relics that had been made during the occupation of the site by the organized tribe.

Many of the specimens were removed to the provincial museum at the Normal School on Gould Street. Other specimens were located in private collections. When the writer was a boy living in the east end of Toronto, his father, the late Price Jackes, a twin brother of the Baldwin Jackes referred to in the government report, had a large collection of these Indian relics. The writer has often examined them and I recall the very high degree of finish and the elaborate decoration of the various pottery items. Unfortunately, during the years and many movings, this collection of Indian relics has been lost.

Such then was the first great settlement of North Toronto. The question will naturally arise as to why the Indians did not construct their great town on the waterfront. There are two answer to that question. The North Toronto site was well hidden and was surrounded by dense forest. And of almost equal importance to community life, it had an unfailing water supply in the artesian spring. ♦