Herman Kempinski was evidently a first cousin once removed to my great-great-grandfather, Rafael Glicenstein, and both came from the town of Konin, Poland.

Herman Kempinski was evidently a first cousin once removed to my great-great-grandfather, Rafael Glicenstein, and both came from the town of Konin, Poland.

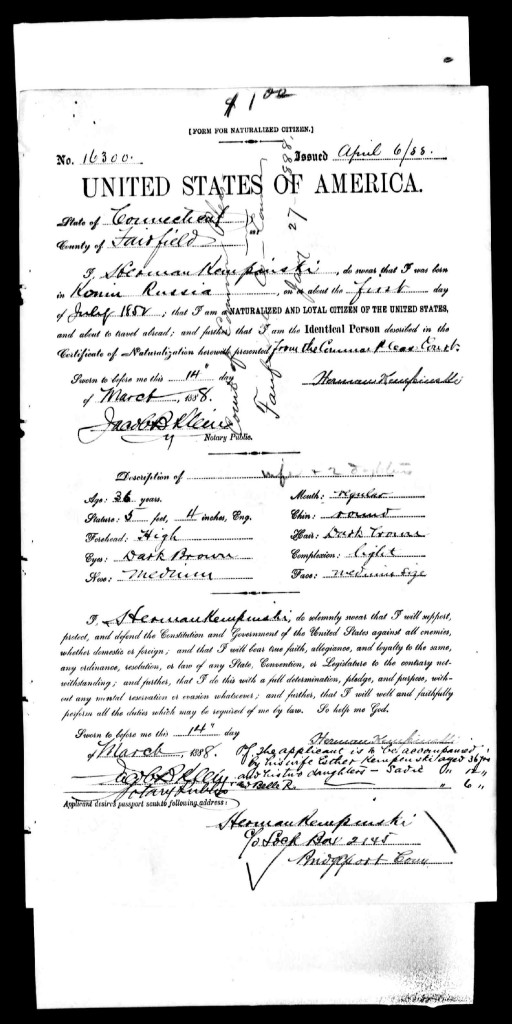

Herman, born about 1854, was one of the many thousands of Russian-Polish Jews to emigrate to the United States in the late 1800s: he left Konin at age 17 in 1872. He settled in Bridgeport, Conn., made a success of himself in business, married and became the father of two daughters.

It was because he wanted to give his elderly parents in Konin the pleasure of meeting their two granddaughters in person that he took his family back to the Old Country in 1888. And there his troubles began — troubles that would eventually be described in depth in a New York Times article on May 25, 1890 under the heading, “He Was the Czar’s Guest.”

The Kempinski family had been in Konin for six months before the authorities took the unwarranted action of arresting Herman and locking him up in the local prison. The charge was that he had evaded military service. His protestations that he was an American citizen fell on deaf ears. Two days later, his family was briefly allowed to see him; when his six-year-old daughter, Sadie, saw his handcuffs, she recognized at once the desperate situation he was in. “Papa, they’ve fixed you now!” she reportedly exclaimed, a remark that, according to the New York Times, “greatly impressed the whole family by its wisdom.”

By continuous payments of bribes, he managed to have himself transferred to a more comfortable jailhouse in Kalisz — his family settled into a nearby farmhouse — and insured daily coffee, bread and water enough for survival. Additional sums were paid for simple luxuries such as a pillow, which cost 100 kopecks.

Conditions were so unsanitary that he became ill and was sent to hospital. He told the newspaper, “If I hadn’t had money I don’t believe I could have come out of the prison alive.” Over the period of his 13-month incarceration, he spent $10,000, a sum that by today’s dollars, is probably close to half a million dollars.

At one point in his imprisonment, Herman signed a letter that he was told was a request for a pardon; it contained the false admission that he was not an American citizen, which complicated his case immensely. The American State department worked for months to secure his release. One day he was summoned from his cell to the warden’s office where the “procurator” read a dispatch from the Emperor’s officials announcing his pardon. He and his family sailed back to America aboard the Augusta Victoria.

At one point in his imprisonment, Herman signed a letter that he was told was a request for a pardon; it contained the false admission that he was not an American citizen, which complicated his case immensely. The American State department worked for months to secure his release. One day he was summoned from his cell to the warden’s office where the “procurator” read a dispatch from the Emperor’s officials announcing his pardon. He and his family sailed back to America aboard the Augusta Victoria.

An article in the New York Times of November 9, 1890, recounts the Kempinski case and describes numerous other cases in which the American Secretary of State James Blaine made entreaties to the Russian government on behalf of Jewish American travellers who were being harassed. It adds the additional details that many of Herman Kempinski’s friends in Bridgeport, including the mayor, wrote beseeching letters to Blaine, requesting his intercession. It also provided a message that the prisoner issued soon after his arrest:

“If, with the help of God, I will get back to the old B’port safe again, I will have lots of news to tell you, for which paper would not be enough, what I went through since I got to this damn country . . . Hurrah for the Stars and Stripes! . . . Three cheers again for the Red, White and Blue. There is no better place in the world.”

Based on the information contained in the first-mentioned New York Times article, I attempted to trace the family of Herman Kempinski. His wife was Ernestine Daum Kempinski; their daughter, Sadie Stein, evidently died in 1957 and was buried in B’nai Israel Cemetery in Fairfield, Conn. From there the trail went cold, and I have not made any further investigations.

Anyone who googles the name Herman Kempinski will receive links to both New York Times articles mentioned above, as well as a couple of other sources from the 1890s. Thus, the details of an obscure 125-year-old misadventure in the life of a Jewish American traveller may be brought back quickly to hand. ♦