With factories, warehouses, train stations and other relics of the past strewn about central Manchester like so many children’s toys, the city where the industrial revolution began has been quietly adapting to the post-industrial age. The place that J.B. Priestley once described as “an Amazonian jungle of blackened brick” has cleaned up its image in recent years as it aspires to live up to Benjamin Disraeli’s observation that, “Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens.”

With factories, warehouses, train stations and other relics of the past strewn about central Manchester like so many children’s toys, the city where the industrial revolution began has been quietly adapting to the post-industrial age. The place that J.B. Priestley once described as “an Amazonian jungle of blackened brick” has cleaned up its image in recent years as it aspires to live up to Benjamin Disraeli’s observation that, “Rightly understood, Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens.”

Crisscrossed by a former ship canal and an elevated Victorian-era railway built in a Romanesque style, the inner city’s Castlefield district also boasts the ruins of a Roman fort almost 2,000 years old. Nearby, a cluster of dilapidated industrial buildings has been remodeled into two major tourist attractions — the Granada Studios Tour and the Museum of Science and Industry — both rooted in the clean, modern communications and information age.

Capitalizing on the immense popularity of Granada-produced TV shows and series such as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Brideshead Revisited and the Coronation Street, the Granada Studios Tour invites visitors to peek behind the scenes of an active studio and to inspect the sets of their favourite programs from “the telly.” (The sets are open to the public on all but the few days a month when crews and casts are in production.)

On the Coronation Street set, which is unprotected from the elements and resembles an ordinary street, fans of the long-lived show visit the Duckworth home, the Rovers Return pub, Rita’s corner shop and other familiar landmarks. Meanwhile, on the Baker Street set (which is enclosed beneath a dark and lofty roof), visitors chat with costumed street performers who present themselves as the master detective’s Victorian neighbours.

On the Coronation Street set, which is unprotected from the elements and resembles an ordinary street, fans of the long-lived show visit the Duckworth home, the Rovers Return pub, Rita’s corner shop and other familiar landmarks. Meanwhile, on the Baker Street set (which is enclosed beneath a dark and lofty roof), visitors chat with costumed street performers who present themselves as the master detective’s Victorian neighbours.

Mr. Holmes is not at home, he has just gone out with Dr. Watson, they tell callers to 221-B Baker Street, who are then invited into the premises anyways via a side door. Inside, one finds the fictitious detective’s roped-off living-room-cum-laboratory as well as an authentic Museum of Criminology, which holds possibly the largest collection of Sherlock Holmes-related memorabilia in Britain.

The Granada Studios Tour receives some 750,000 visitors each year, making it one of the country’s top attractions. With the hour-long Backstage Tour and various other creative new-age attractions (including Robocop: The Ride and The UFO Zone), visitors stay an average of five or six hours for a ticket price of approximately CND $26 for adults, $20 for children.

Next door, at the Museum of Science and Industry, children are encouraged to become detectives for themselves as they ferret out the great mysteries of science and mechanical engineering. If the Granada Studios Tour exposes trade secrets of the modern television industry, the Museum of Science and Industry focuses on the mechanical inventiveness that sustained the industrial revolution over the last two centuries, changing both Manchester and the world.

The Museum is housed in five historic buildings, including an 1830 passenger station that is the oldest building of its kind in the world, built in an era when people commonly believed that high-speed train travel could be fatal.

The Museum is housed in five historic buildings, including an 1830 passenger station that is the oldest building of its kind in the world, built in an era when people commonly believed that high-speed train travel could be fatal.

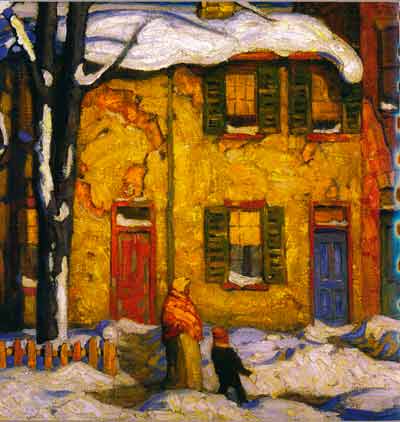

The Making of Manchester, a display that focuses on the city’s booming growth after becoming the centre of the world’s cotton industry in the late 18th century, does not gloss over the poverty, pollution, bad health and shocking housing conditions that resulted. Indeed, it brings to mind the hellish, apocalyptic images still associated with Britain’s second-largest city: the dreary factories, the dirty canals, the darkened streets, the steam-powered machines, the coal furnaces, the smoke-belching chimneys that rose above the din like so many towers of Babel.

The Museum’s Power Hall holds a diverse assortment of chugging turbines, water wheels and engines powered by hot air, diesel and steam, many recovered from local factories. All are in operating condition and are started up daily. There is also a display of locally-built cars and motorbikes: Manchester is the place where Henry Ford established his first factory outside America, and where the first Rolls-Royce automobile was produced; Mr. Rolls and Mr. Royce first met in the lounge of the local Crowne Plaza Midlands Hotel.

The Museum also offers an Air and Space Gallery, a hands-on science learning centre, and intriguing displays of antique trains, cameras, scientific instruments, and gas and electric appliances used earlier in the century. The admission price of roughly $10 for adults, $5 for children, is good for a half-day or even an all-day visit.

Throughout central Manchester, once-dilapidated textile warehouses have been restored into offices, restaurants, pubs, condominiums, hotels — each, like the inner city itself, given a new lease on life. For instance, two former warehouses, India House and Lancaster House, have become exclusive condominium blocks, while another two buildings have been revitalized as the Victoria and Albert, an award-winning hotel. Such developments have regentrified the once-deserted downtown, adding thousands of residents in recent years.

Throughout central Manchester, once-dilapidated textile warehouses have been restored into offices, restaurants, pubs, condominiums, hotels — each, like the inner city itself, given a new lease on life. For instance, two former warehouses, India House and Lancaster House, have become exclusive condominium blocks, while another two buildings have been revitalized as the Victoria and Albert, an award-winning hotel. Such developments have regentrified the once-deserted downtown, adding thousands of residents in recent years.

As if to compensate for the business-oriented commercial ethic that has always prevailed here, Mancunians like to point out that theirs is a city possessing four university campuses, two football teams, and numerous art galleries, heritage theatres and important libraries. From both an architectural and scholastic viewpoint, the John Rylands Library is an outstanding institution. The library, which opened in a gorgeous red-brick gothic building in 1900, holds an almost unparalleled collection of early western manuscripts, including a fragment of a New Testament scroll from the 2nd century.

Eminently walkable, the downtown core boasts more Victorian architecture than any other city in Britain except Glasgow, says freelance city guide Barbara Frost. Dating from 1868, the Alfred Waterhouse-designed Town Hall is a chilling masterpiece of Victorian Gothic, complete with elaborate grand staircases, massive leaded-glass windows and a plethora of pointed arches. (Astonishingly, the building was criticized in its day for not being gothic enough.)

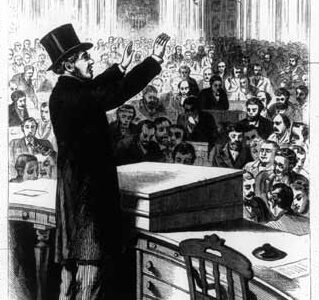

Particularly noteworthy are the series of murals in the grand hall depicting Manchester’s history, painted in a pre-Raphaelite style by Ford Madox Brown. One painting shows John Kay, inventor of the flying shuttle, attempting to escape as a group of hostile Luddites storms his home.

Never ones to oppose progress as the Luddites did, Mancunians are busy as always, cleaning up their act as they industriously reinvent Manchester for the post-industrial age. ♦

© 2006