Tar and Feathers for an Obstinate Juryman — Some Attempted Escapes — A Picture of Desolation

From the Toronto Daily Star, June 15, 1901

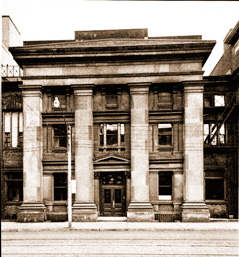

Grim, solemn, and even sullen seems the aspect of the old Court House on Adelaide street east, which has stood as a monument of integrity for half a century. The building itself has about it the air of solemnity which accompanies similar buildings wherein right, or the law, combats the wrong, and where the intricacies of the law in both criminal and civil cases are expounded.

Grim, solemn, and even sullen seems the aspect of the old Court House on Adelaide street east, which has stood as a monument of integrity for half a century. The building itself has about it the air of solemnity which accompanies similar buildings wherein right, or the law, combats the wrong, and where the intricacies of the law in both criminal and civil cases are expounded.

There is now an almost entire absence of the former activity which marked it in its palmy days. With very much the same awe and respect with which the citizens of today view the mighty pile which raises its lofty grandeur on Queen street, no doubt the citizens of fifty years ago looked on the old Court House in Adelaide street. The building was originally of white brick and stone, but has become endowed with a darker hue from the smoke and dirt of a great city.

In accordance with the architectural tendencies of its day, the building is a low one, with four immense stone columns, two one each side of the entrance — through which has passed a generation or two of hurrying feet. The young lawyer of fifty years ago, who, with alluring ambition and fame beckoning onward, grasped his brief bag and hurried to represent his client, has become the King’s Counsel or judge of to-day. Nearly all the learned judges before whom his cases were argued have been called to a higher bar. The old building yet stands, and could its walls talk, many would be the varied stories of human interest, of heart-rendings and rejoicings, that they could tell.

RUSTY HINGES.

Even as you enter the building the hinges on the door cry out in agony, caused by years of faithful service. These doors have received all kinds of knocks. Their end may be far off, but doubtless before long they will be relegated to the oblivion of a second-hand dealer’s yard.

An unmistakably well-worn path leads the inquiring stranger in either direction from the door. No matter which way is taken, a flight of stairs carries one to the first floor, the scene of many a memorable struggle. Here in the Assize Court the combatants — the representative of the Crown, personating law and justice, and the counsel for the criminal — strove on memorable occasions for the rich stake of a human life. The noon-day sun casts a wan touch on the faded room.

One door reads “Public,” and the opposite one “Jury.” Following the door labelled “jury,” a well-worn passage leads to the jury box, where twelve good men and true oft listened to the words “may it please your honour, gentlemen of the jury.” The chairs are still in the positions in which thoughtless jurymen had pushed them when leaving the box after hours of wearied deliberations within a locked room. The counsels’ tables still have the blotters flung carelessly just as they were left when learned lawyers blotted their jottings and hastily threw them aside.

The prisoners’ dock still remains the center of attraction, even though now vacant. The axes, which, according to an ancient tradition, were turned towards a condemned prisoner, appear lost. While standing looking at the dock the mind involuntarily wanders to the prisoners who have stood there, heard their case tried, anxiously awaiting the jury, felt the awful silence preliminary to the verdict, and left its environments encircled in iron, condemned criminals, or joyful, free men, to be clasped by loved ones who never would believe them “guilty.”

There, too stands the judges’ bench, whereon have sat Judges Harrison, Cameron, Hagarty, Galt, Rose, McKenzie, and others, many of whom have gone to higher courts. But follow a well-worn track in the floor which leads to the prisoners’ temporary quarters and down a narrow, dark, and gloomy stairway which brings one to the cells, where many a man has sat awaiting the conveyance to carry him to the prison where he should receive the just reward of his offence. The prisoners’ cell is a dark room with one heavily-barred window, high up in the wall, with a bench going around the room, whereon have sat hundreds of thieves, and murderers, and other felons.

ATTEMPTED ESCAPES.

It is yet within the recollection of some of the older county peace officers of more than one attempted escape from this room. One very warm day a kindly constable was taking a pail of water into the cell to alleviate the thirst of the wretched inmates. He had the pail in one hand, and . . . was unfastening the bolts, when a sudden pressure was brought to bear. Realizing the situation, and knowing that several iron pokers and handles were lying around a stove nearby, and that there was an open door behind him, he dropped the pail, opened the door suddenly, and with a quick and well-directed punch sent the would-be criminals reeling across the cell, enabling the door to be closed and the bolt shot into position.

The noise of the falling pail and the racket caused by the slamming of the door aroused the court sitting above. Constables, reporters, and jurymen rushed below, and asked the constable in charge what was the matter. “Nothing,” was the only response, but officially it became known that the combined attempt of a murderer and other offenders to escape had been frustrated.

Again, prisoners got out of the only window in some way, and, finding escape at the rear of the building impossible owing to a high fence, coolly walked back through the corridors of the court house and emerged on Adelaide street.

Adjoining the court room with its faded splendor is the judge’s room, where the gown wig and insignia of office were donned. This room had the peculiarity that a kindly old gentleman entered it with a smile, and a familiar greeting to a constable or lawyer standing near, and emerged from it decked out in the solemn majesty of the law, an austere judge ready to mete out justice to all offenders.

Next to the judge’s room was the jury room.

A TAR-AND-FEATHER STORY.

Probably no room in the whole building, could its walls repeat what it had heard in a half a century, tell more tales of exhortations, coaxing, threatening, or persuasiveness. Here the men, who would “well and truly try and a true deliverance make between our Sovereign lady the Queen and the (defendant) . . . deliberated for many an hour. It is an ordinary room, like many of the others in the building, but the fate of many a man has hung upon the decision which had been reached when the jury filed beneath its fateful portal. . . .

One case in particular is recalled: when the case had been submitted to the jury, and they retired to the room at 4.30 in the afternoon. At ten o’clock that night no decision had been reached, and the judge ordered the jury to be locked up for the night. This was done, but in about an hour’s time a small piece of paper appeared under the door. It bore the words, “Please send out and get 25 cents worth of tar and feathers, we want to tar and feather a juryman.”

Later on another note appeared asking, “Would you be kind enough to send for a piece of rope thicker than a clothesline? We want to hang a juryman.” There was one obstinate juryman who had been a friend of the prisoner, and refused to return a verdict of guilty, but acquiesced before morning.

On one occasion a jury was found to have procured bottles of liquid refreshment from a hotel nearby by the aid of a string hung out of the window, and the enlisted services of a newsboy. A constable happening along was, to say the least, shocked to see such a heinous offence being committed.

BEER AND SANDWICHES.

Another jury that had been locked up for the night was known to have got possession of a basket containing sandwiches and bottles of ale, which the county constables in charge of them had thoughtfully clubbed in a bought for themselves to help pass the weary vigils of the night. The constable’s first intimation of the loss was to receive the basket from the jury room with the note, “The ale was excellent, but there were not enough sandwiches.”

One obstinate juryman was known on entering the jury room to have chosen the softest cordwood stick of a bunch that was used in the big box stove, and told the other jurors he believed the prisoner “not guilty,” and asked to be called when they had reached a decision. The cordwood stick acted as a pillow for ten hours, and at the end of that the verdict of “not guilty” had been reached.

Not only is the Assize room associated with the many historic events which startled the world, but the County Court room and the Division Court room all have history stored in every corner and in the venerable dust that hides their former magnificence. These walls have witnessed many a well-fought legal battle in both civil and criminal cases, but the glory has departed. Their place has been usurped by the new building on Queen street.

Many of the rooms on the floor above the court contain the papers of almost three quarters of a century, many yellow with age in harmony with their musty surroundings.

Downstairs the Council Chamber of the York County Council still re-echoes the wisdom of its councillors, who govern the county. This chamber, with its gorgeous warden’s chair overhung with purple silk, is really the only meting place in the building. ♦

◊ The County of York Court House, 57 Adelaide Street East was built ca 1851 by Cumberland and Ridout, architects. Eric Arthur, in No Mean City, described the Greek-influenced front of the building as “austere, heavy, and forbidding . . . . One thinks immediately of the suggested epitaph for Sir John Vanbrugh, the architect of Blenheim Palace — ‘Lie heavy on him, Earth, he laid many a heavy load on thee.'” After the Court vacated to City Hall on Queen Street West, the building became home to the Arts and Letters Club until 1913, which entertained Sir Wilfried Laurier and many of Toronto’s finest citizens there before moving to St George’s Hall, Elm Street. Today the former Court House is home to the Court House Restaurant.

◊ The County of York Court House, 57 Adelaide Street East was built ca 1851 by Cumberland and Ridout, architects. Eric Arthur, in No Mean City, described the Greek-influenced front of the building as “austere, heavy, and forbidding . . . . One thinks immediately of the suggested epitaph for Sir John Vanbrugh, the architect of Blenheim Palace — ‘Lie heavy on him, Earth, he laid many a heavy load on thee.'” After the Court vacated to City Hall on Queen Street West, the building became home to the Arts and Letters Club until 1913, which entertained Sir Wilfried Laurier and many of Toronto’s finest citizens there before moving to St George’s Hall, Elm Street. Today the former Court House is home to the Court House Restaurant.