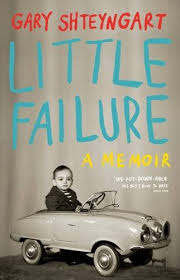

Little Failure, by Gary Shteyngart. Published by Random House

From the Canadian Jewish News, May 2015

In this funny, self-deprecating memoir, Gary Shteyngart tells the story of his family’s migration from Russia to America in 1979, when he was seven years old, and his subsequent transformation not only into a fully-grown Americanized Jewish male, but also a successful writer.

In this funny, self-deprecating memoir, Gary Shteyngart tells the story of his family’s migration from Russia to America in 1979, when he was seven years old, and his subsequent transformation not only into a fully-grown Americanized Jewish male, but also a successful writer.

His parents regarded him as a disappointment when he was a child, he reports, and continued doing so even when he graduated from writing courses in college with honours. “My mother was developing an interesting fusion of English and Russian and, all by herself, had worked out the term Failurchka, or Little Failure,” he writes, explaining the title of the book.

Shteyngart burst into the literary mainstream with his first novel, The Russian Debutante’s Handbook in 2002, and won distinguished literary awards with his two subsequent novels, Absurdistan (2006) and Super Sad True Love Story (2010). The fact that many segments of Little Failure first appeared in Travel & Leisure, The New York Times, The New Yorker, New York, Threepenny Review, GQ and other prestigious publications demonstrates how sought after our little “failurchka” has become in the rarefied world of modern American letters.

Shteyngart writes with a frenetic, comical energy as though he were on steroids, so it is somehow not surprising that he is subject to occasional panic attacks. The book opens with a description of one such attack, which occurred on his first trip back to Russia in 1999 when he was 27 years old, three years before he signed his first book deal.

He was standing outside the Chesme Church five blocks from his family’s former home in St. Peterburg, a building whose “sugar-coated spires and crenellations” make it more confection than architecture. Among other things, the book is a quest to understand why the church, and an old association with a toy helicopter, could have filled him with such panic and dread. (Recalling his childhood, he remembers his mother explaining that the reason he was afraid of everything was “because you were born a Jewish person.”)

Shteyngart deals with his family’s past en passant, providing the condensed Reader’s Digest version of the tragic fate of his grandparents and many aunts, uncles and cousins.

“As I march my relatives onto the pages of this book, please remember that I am also marching them toward their graves and that they will most likely meet their ends on some of the worst ways imaginable,” he relates in a Nabokovian aside. “But they don’t have to wait for the Second World War to start. The good times are already rolling in the 1920s. While my great-grandpa Stone Horn [Shteyngart] is being killed in one part of the Ukraine, great-grandpa Miller is being killed in another part.”

“As I march my relatives onto the pages of this book, please remember that I am also marching them toward their graves and that they will most likely meet their ends on some of the worst ways imaginable,” he relates in a Nabokovian aside. “But they don’t have to wait for the Second World War to start. The good times are already rolling in the 1920s. While my great-grandpa Stone Horn [Shteyngart] is being killed in one part of the Ukraine, great-grandpa Miller is being killed in another part.”

The Soviet Union was falling apart and finally allowed its Jews to leave in exchange for tons of grain and some high-tech gizmos from the United States, he explains. The Shteyngarts flew from Moscow to East Germany, then to Vienna, then spent five months in Rome before arriving in New York.

“Coming to America after a childhood spent in the Soviet Union is equivalent to stumbling off a monochromatic cliff and landing in a pool of pure Technicolor,” he writes, presenting a typical example of his vivid prose. “The intensity of arrival will not abate. Everything is revelation. . . .”

But life quickly settles into a dreary mockery of the American Dream: “We are the Grain Jews, brought from the Soviet Union to America by Jimmy Carter in exchange for so many tons of grain and a touch of advanced technology. We are poor. We are at the mercy of others: food stamps from the American government, financial aid from refugee organizations, secondhand Batman and Green Lantern T-shirts, and scuffed furniture gathered by kind American Jews.”

There are some lovely passages here that seem to demonstrate that the author has the soul of a beat poet. For example, the time the family was convinced it had won $10 million because of a letter received from the Publishers Clearing House. Or the time 15-year-old Gary feels a soaring sense of liberation as he travels by subway and plays frisbee with some new-found non-Jewish friends in the park.

Little Failure is essential a coming-of-age tale that focuses on the author’s progress with both women and writing. One evening, as he is coming home from a date, his father queries him: “ ‘Nu, are you a man yet?’ He’ll lean in and smell the air around me. And I will sigh and say, ‘Otstan’ ot menya,’ Leave me alone, and stomp, stomp, stomp upstairs to my Playboys and my Essays That Worked for Law School.”

Ultimately he tells of his various girlfriends as well as a friendship with an older writer, John, who becomes his benefactor, role model and father figure. We also learn the reason for his panic attack near the Chesme Church: because his father once gave him a bloody nose there for playing with a toy helicopter. “Oh, Igor, you are so sensitive,” his mother tells him. “And that is why you are a writer.”

Having endured a “great uprooting of language and familiarity” in coming to America, Shteyngart laments, in true Nabokovian fashion: “There are more memories here I would like to capture and display for you, if only I were faster with my net.” But such allusions to Vladimir Nabokov’s classic memoir Speak Memory do not serve him well and tend to highlight his own thematic shallowness. Shteyngart’s flash-in-the-pan brilliance delivers no enduring insights into himself or the human condition.

For a more realistic, serious and detailed treatment of Russian Jewish immigration, see Maxim D. Shrayer’s Leaving Russia: A Jewish Story (Syracuse University Press). It’s a serious, heavyweight, literary work: “Narrated in the tradition of Tolstoy’s confessional trilogy and Nabokov’s autobiography, this is a searing account of the KGB’s persecution of refuseniks, a poet’s rebellion against totalitarian culture, and Soviet fantasies of the West during the Cold War.”

Toronto’s own David Bezmozgis has also given us a fine novelistic treatment of the subject. Published in 2011, The Free World is a compelling entry into the century-old and still-expanding genre of Jewish immigrant fiction. ♦