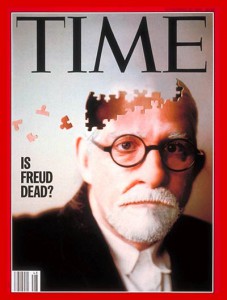

The November 29 (1993) issue of Time Magazine featured a likeness of the founder of psychoanalysis on its cover with the caption, “Is Freud dead?” in conscious parody of the magazine’s well-remembered “Is God Dead?” cover of April 1966.

The November 29 (1993) issue of Time Magazine featured a likeness of the founder of psychoanalysis on its cover with the caption, “Is Freud dead?” in conscious parody of the magazine’s well-remembered “Is God Dead?” cover of April 1966.

Inside, several articles asserted that recent chemical discoveries and psychoanalytic treatment modalities of dubious value have thrown Freudian theory into disrepute. Defenders of this pioneering cartographer of the unconscious contend, however, that his scientific reputation cannot be so easily tarnished.

Sigmund Freud died in London in 1939 of the throat cancer that had afflicted him even as the Nazis chased him from his native Vienna just over a year earlier. Today his former residences in both cities are museums that illuminate his life and the psychoanalytic movement he founded. They also demonstrate that the legend of this 20th-century Jewish giant still has the power to hold us in deep hypnotic thrall.

The famous couch upon which psychoanalysis was born now reposes in London. So do the 2,000 or so classical, Egyptian and Oriental antiquities that Freud prized, as well as the greater part of his library and much of the household furnishings from Vienna.

“The family was able to take all their possessions from Vienna with them, which was very unusual for Jews at that time,” says Erica Davies, acting director of the Freud Museum in London (20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead NW3) where many of these objects are seen by some 12,000 visitors annually. The museum, which opened in 1986, was the home where Sigmund Freud’s daughter Anna lived and practiced until her death in 1982.

“The family was able to take all their possessions from Vienna with them, which was very unusual for Jews at that time,” says Erica Davies, acting director of the Freud Museum in London (20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead NW3) where many of these objects are seen by some 12,000 visitors annually. The museum, which opened in 1986, was the home where Sigmund Freud’s daughter Anna lived and practiced until her death in 1982.

Many of Freud’s possessions are also on display in his former flat at 19 Berggasse in the 9th district of Vienna, where he lived and practiced for nearly half a century. The intimate museum there, called Sigmund Freud House, is filled with books, furniture, small statues, paintings and other genuine Freudiana. The establishment also houses an important research library and publishes a journal that reaches psychiatric professionals around the globe.

The room where the first psychiatric patients in the world underwent psychoanalysis is now the office of the museum’s general secretary, Ingrid Scholz-Strasser. One senses that the famous couch is sadly missed. According to Scholz-Strasser, the Viennese remain fiercely proud and possessive of the Freud legend.

Last year, posters all over town were promoting the big splashy musical Freudiana which was playing at the historic Theatre an der Wien. Despite ticket prices of $85 and more, the play enjoyed a long profitable run, during which the Hotel Bristol offered a nightly “Freudiana” post-theatre dinner.

Last year, posters all over town were promoting the big splashy musical Freudiana which was playing at the historic Theatre an der Wien. Despite ticket prices of $85 and more, the play enjoyed a long profitable run, during which the Hotel Bristol offered a nightly “Freudiana” post-theatre dinner.

How might Freud have perceived Time’s untimely cover? Possibly just as he would have regarded its April 1966 precursor: as evidence of society’s repressed patricidal tendencies.

* * *

Vienna’s Jewish Museum, Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) and the elegant Stadtempel (old synagogue, dating from 1825) are important sites of Jewish interest in the Austrian capital. Don’t be put off by the armed guards that patrol outside the synagogue: they were posted there after a terrorist attack in the 1970s.

After seeing the synagogue, visit Arche Noah (Seitenstettengasse 2), the cosy kosher restaurant around the corner. “Heritage and Mission: Jewish Vienna” is the name of a lavish 12-page brochure that describes the city’s ten centuries of rich but ultimately tragic Jewish history. To receive a complimentary copy, write to Jewish Welcome Service, A-1010 Vienna, Stephansplatz 10, Austria. Website: http://www.jewish-welcome.at/

* * *

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, who at 65 is Austria’s foremost artist, is partly Jewish, and that’s as good an excuse as any to include the KunstHaus, the Viennese museum devoted to his work, in this week’s column. Hundertwasser’s trademark fantastic and organic forms are as recognizable in his paintings as they are in his architecture.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, who at 65 is Austria’s foremost artist, is partly Jewish, and that’s as good an excuse as any to include the KunstHaus, the Viennese museum devoted to his work, in this week’s column. Hundertwasser’s trademark fantastic and organic forms are as recognizable in his paintings as they are in his architecture.

Having banished any influence of the straight rule, the Vienna-born artist adopted the spiral as a sort of esthetic template.

Opened in 1991, the Kunsthaus’s walls are purposely uneven and its tiled floors as irregular as a field. The building gives the feeling of being a magical house belong to a troll, or a set from a medieval fairy-tale. Filled with canvases and architectural models, it houses the only permanent collection of the artist’s work anywhere.

Hundertwasser, who likes to do a thing once and then move on, designed several distinctive residences in Vienna, and redesigned St. Barbara’s Church in Bauernbach, all of which draw many visitors. Ever the environmentalist, he beautified a highly visible municipal incinerator in the Austrian capital several years ago, inadvertently creating a local stir.

“People felt that he should try to find a way to eliminate garbage rather than to decorate it,” according to museum spokesperson Frau Sabine Schmeller. “People are very emotional about this.”

Hundertwasser lost part of his family in the Holocaust. In his museum, see his ponderous attempts to combine Jewish and Arabic design elements. The KunstHaus, Untere Weissgerberstrasse 13, Vienna 1030. ♦

© 1993

Freud Returns to Vienna

The play “Freudiana” draws nearly full houses

In the first third of this century, on his frequent evening walks along the ring that encircles Vienna’s Old City, Sigmund Freud used to pass within a few blocks of the Theatre an der Wien, the landmark playhouse where Beethoven once lived and Strauss’s “Fledermaus” premiered. Last year, “Freudiana,” a whimsical musical about the renowned father of psychoanalysis, also made its world debut here, and continues to draw nearly full houses.

Freudiana has been as heavily promoted as Vienna’s well-attended production of Phantom of the Opera. Like Phantom, it is an exciting, full-blown, no-holds-barred, theatrical experience, strong on spectacle to mask its deficiencies in plot, theme and other Aristotelian virtues. The choreography is excellent and the music, written by Eric Woolfson and Alan Parsons, is slick and hummable and possesses a certain Andrew Lloyd Webberish appeal. Again like Phantom, Freudiana commands top shilling at the box-office: $85 and up per seat. Unlike Phantom, however, its title character appears only for a moment, a silhouette on a frosted glass door, smoking a trademark cigar. Despite its name, there’s very little of Freud in Freudiana.

The story concerns a young American tourist named Erik, shy and withdrawn, who gets left behind on a tour of the Freud Museum in London, and is accidentally locked in for the night. When he falls asleep on Freud’s legendary couch, an intriguing Daliesque dream sequence erupts amidst clouds of dry-ice fog. By this time, thanks to the miracle of hydraulic lifts, Freud’s study has disappeared, replaced by smoke and mirrors and dazzling light effects.

Over the next two hours, Erik’s awkwardness with women disappears as well. Confronting a circus of peculiar archetypal characters like the depressive Wolfman and compulsive-obsessive Ratman, he hurtles headlong through his own neuroses via a series of increasingly bizarre and colorful dance numbers and dream landscapes — a sort of psychoanalytical “Long Night’s Journey Into Day.”

Well into the second act, Erik meets the literary detective Sherlock Holmes who helps him re-enact the Oedipal drama of patricide in a visually stunning triangle of blasing lasers in a London underground station and tunnel. This is entertainment? Yes: it’s a frothy cathartic celebration of Freud and things we associate with him: dream fantasies, double-entendres, slips of the tongue that hint at dark secrets of the soul, rich symbolism, plenty of sex, repressed and otherwise — plus some astonishing theatrical technopyrics.

Newspaper reviewers have been generally enthused by the show, which one called “a sensational trip into the realm of dreams and nightmares.” Less keen about the story-line and performances, Die Presse raved about the spectacle: the theatre becomes “a sorcerer’s lab of stage technique … never has so much optical witchcraft been shown before.” The producers hope to mount the show in London or New York after it finishes its run in Vienna this spring.

Freud would have recognized little of himself or his work in this enterprise. Neither does Ingrid Scholz-Strasser, general secretary of the Sigmund Freud House, located at 19 Berggasse in Vienna, the flat Freud lived in for nearly half a century until fleeing the Nazis in 1938. Like the home he occupied briefly in London before his death in 1939, his Vienna flat has been turned into a museum filled with books, furniture, small statues, paintings and other genuine Freudiana.

Scholz-Strasser invites the reporter to sit on the couch in her office, which happens to be the very room, indeed the very spot, where the world’s first psychiatric patients underwent psycho-analysis on Freud’s famous couch. But now it is the visitor who possesses the notebook and the “doktor” who makes the confession: the producers sent museum staff an advance script, asking for advice, then ignored their suggestions. “They said it was going to be a musical, not a scientific presentation,” she recalls.

Scholz-Strasser attended the opening anonymously but was unimpressed. “It’s not my business to judge whether it’s good or bad entertainment,” she says. “All I can judge is whether it’s accurate — and we think in many points it gives an inaccurate view of psycho-analysis and an inaccurate history of psycho-analysis, so we have to distance ourselves from it.”

Psycho-analytic purists who see this production should have their heads read. Everyone else should be entertained, perhaps despite themselves. Knowledge of German is not essential; indeed, the lack of it may even be an advantage. Those who hunger for more substantial fare might do well to visit the Hotel Bristol along the Ringstrasse, where an after-theatre “Freudiana” thematic dinner is served nightly. ♦

© 1990